An Overview of the

Analysis and Transmission of Aperiodic Signals

Aperiodic Signal Representation by Fourier

Integral

An aperiodic function will

never repeat, although technically speaking an aperiodic function can be considered

similar to a periodic function with an infinite period. In order to show that

an aperiodic signal can be expressed as a continuous sum (or integral) of

infinite exponentials, a limiting process is applied. In order to represent an

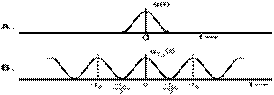

aperiodic signal f(t), such as the signal shown

in Fig. 1.1a by infinite exponential signals, a new periodic signal

fT0fT0

must be formed by repeating the aperiodic signal f(t)

every T0 seconds, shown in Fig. 1.1b. The period is made just long enough to

not overlap between each repeating pulse. This periodic signal

fT0fT0

is represented by an exponential Fourier series. By

letting

T0→∞T0→∞

, the pulses

in the periodic signal repeat themselves after an infinite interval, therefore:

limT0→∞fT0(t)=f(t)limT0→∞fT0(t)=f(t)

The Fourier series

representing

fT0fT0

will thus also represent f(t) in the limit

T0→∞T0→∞

. The

exponential Fourier series can be represented for

fT0fT0

as follows

fT0(t)=∑n=−∞∞Dnejnω0tfT0(t)=∑n=−∞∞Dnejnω0t

(1.1)

by which

Dn=1T0∫T02−T02fT0(t)e−jnω0tdtDn=1T0∫−T02T02fT0(t)e−jnω0tdt

(1.2a)

FIGURE 1.1.

Construction of a periodic signal by periodic extension of f(t)

Figure 1.1 represents the

construction of a periodic signal by periodic extension of f(t)

and

ω0=2πT0ω0=2πT0

(1.2b)

Figure 1.1a and 1.1b show

that integrating

fT0fT0

over

−T02,T02−T02,T02

is exactly the same as if you were to integrate over

(−∞,∞)(−∞,∞)

.

Simplifying the integration bounds, Eq 3.2a

is now expressed by

Dn=1T0∫∞−∞fT0(t)e−jnω0tdtDn=1T0∫−∞∞fT0(t)e−jnω0tdt

(1.2c)

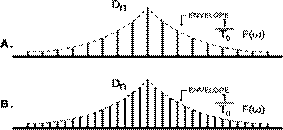

An interesting phenomenon is

that the spectrum changes at T0 increases. To better understand this odd behavior,

F(ω)F(ω)

is defined as a continuous function of

ωω

, as

F(ω)=∫∞−∞f(t)e−jωtdtF(ω)=∫−∞∞f(t)e−jωtdt

(1.3)

The last two equations above

show that

Dn=1T0F(nω0)Dn=1T0F(nω0)

(1.4)

What this shows is that the

Fourier coefficients Dn are (1/T0 times)

the samples of

F(ω)F(ω)

spaced uniformly at intervals of

ω0ω0

rad/s, as shown in Fig. 1.2a. For simplicity, Dn and

F(ω)F(ω)

are assumed to be real in Fig. 1.2. Letting

T0→∞T0→∞

by doubling T0 repeatedly, halves the fundamental

frequency

ω0ω0

; this operation is used so that there are twice as many components

(or samples) in the spectrum. Consequently, by doubling T0

, the envelope

(1T0)F(ω)(1T0)F(ω)

is halved, shown in Fig 1.2b. If T0 is doubled over and

over again, the spectrum will become denser while its magnitude becomes

smaller. Nothing that in the limits

T0→∞T0→∞

,

ω0→∞ω0→∞

, and

Dn→∞Dn→∞

, the

relative shape of the envelope is kept the same. This means that the spectrum

must be so dense that the spectral components are spaced at zero (or infinitesimal)

level! Simultaneously, the amplitude of each component is also zero. This may

seem peculiar at first glance; however, it will be shown that these are classic

characteristics of a very familiar phenomenon. By substituting Eq.

1.4 in Eq. 1.1, the following sum yields

fT0(t)=∑n=−∞∞F(nω0)T0ejnω0fT0(t)=∑n=−∞∞F(nω0)T0ejnω0

(1.5)

Here as

T0→∞T0→∞

,

ω0ω0

becomes extremely small

(ω0→0)(ω0→0)

. Due to

this limit, a more appropriate notation will replace

ω0ω0

,

ΔωΔω

. With this new

notion, Eq. 1.2b is now written as

Δω=2πT0Δω=2πT0

and Eq. 1.5 is now written as

fT0(t)=∑n=−∞∞[F(nΔω)Δω2π]e()jnΔω)tfT0(t)=∑n=−∞∞[F(nΔω)Δω2π]e()jnΔω)t

(1.6a)

Here, Eq. 1.6a shows that

fT0(t))fT0(t))

may be expressed in terms of a sum of infinite exponentials

with frequencies

0,±Δω,±2Δω,±3Δω,...0,±Δω,±2Δω,±3Δω,...

, which is

the Fourier series. In the limit as

T0→∞T0→∞

,

ω0→∞ω0→∞

, and

Dn→∞Dn→∞

, the amount

of the component of frequency

nΔωnΔω

is

[F(nΔω)Δω]/2π[F(nΔω)Δω]/2π

. Thus,

f(t)=limT0→∞fT0(t)=limΔω→012π∑n=−∞∞F(nΔω)e(njΔω)tΔωf(t)=limT0→∞fT0(t)=limΔω→012π∑n=−∞∞F(nΔω)e(njΔω)tΔω

(1.6b)

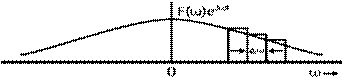

On the right side of Eq 1.6b, the sum is the area under the function

F(ω)ejωtF(ω)ejωt

, as shown

in Fig. 1.3. Thus,

f(t)=12π∫∞−∞F(ω)ejωtdωf(t)=12π∫−∞∞F(ω)ejωtdω

(1.7)

FIGURE 1.2

Change in the Fourier spectrum when the period T0 in Fig 1.1 doubles.

FIGURE 1.3 The

Fourier series becomes the Fourier integral in the limit as

T0→∞T0→∞

The integral on the right

side is known as the Fourier integral. This is the representation of an

aperiodic signal f(t) by a Fourier

integral, rather than a Fourier series. This Fourier integral is essentially a

Fourier series (only in the limit) with fundamental frequency

Δω→0Δω→0

, as shown

in Eq. 1.6.

Assigning

F(ω)F(ω)

as the direct Fourier

transform of f(t), and f(t)

as the inverse Fourier transform of

F(ω)F(ω)

. Another way

to convey this statement is by a Fourier transform pair as stated below

F(ω)=F[f(t)]

and f(t)=F[F(ω)]F(ω)=F[f(t)]

and f(t)=F[F(ω)]

or

f(t)⇔F(ω)f(t)⇔F(ω)

To summarize,

F(t)=∫∞−∞f(ω)ejωtdωF(t)=∫−∞∞f(ω)ejωtdω

(1.8a)

and

f(t)=12π∫∞−∞F(ω)ejωtdωf(t)=12π∫−∞∞F(ω)ejωtdω

(1.8b)

The spectrum of

F(ω)F(ω)

can also be plotted as a function of

ωω

. Because

F(ω)F(ω)

is complex, both the amplitude and angle spectra are as

follows:

F(ω)=|F(ω)|ejθ0(ω)F(ω)=|F(ω)|ejθ0(ω)

Conjugate Symmetry Property

From Eq. 1.8a, if f(t) is a real function of t, then

F(ω)F(ω)

and

F(−ω)F(−ω)

are known to be complex conjugates shown below.

F(−ω)=F∗(ω)F(−ω)=F∗(ω)

(1.9)

Therefore,

|F(−ω)|=|F(ω)||F(−ω)|=|F(ω)|

(1.10a)

θf(−ω)=−θf(ω)θf(−ω)=−θf(ω)

(1.10b)

Consequently, for real f(t), the amplitude spectrum

|F(ω)||F(ω)|

is an even function, and the phase spectrum

θf(ω)θf(ω)

is an odd function of

ωω

. Only for

real f(t), this property known as

the conjugate symmetry property holds true. This

transform of

F(ω)F(ω)

is the frequency domain specification of f(t).

Example

Find the Fourier transform of

e−atu(t)e−atu(t)

By definition of Eq. 1.8a,

F(ω)=∫∞−∞e−jωtdt=∫∞0e−(a+jω)tdt=−1a+jωe(a+jω)t|∞0F(ω)=∫−∞∞e−jωtdt=∫0∞e−(a+jω)tdt=−1a+jωe(a+jω)t|0∞

But

∣∣e−jωt∣∣=1|e−jωt|=1

. Therefore,

as

t→∞,e−(a+jω)t=e−ate−jωt=0t→∞,e−(a+jω)t=e−ate−jωt=0

if

a>0a>0

. Therefore,

F(ω)=1a+jω a>0F(ω)=1a+jω a>0

Existence of the Fourier Transform

In the above example, it was

shown that when a < 0, the Fourier integral for

e−atu(t)e−atu(t)

does not converge. Thus, the Fourier transform for

e−atu(t)e−atu(t)

does not exist if a < 0 (that is,

exponentially growing). Observing from this example, not all signals are

transformable. Any existence of the Fourier transform is assured for any f(t) that satisfies the Dirichlet conditions. The first of the conditions is

as follows

∫∞−∞|f(t)|<∞∫−∞∞|f(t)|<∞

(1.12)

In order to show this holds

true, recall that

∣∣e−jωt∣∣=1|e−jωt|=1

. Thus from

Eq. 1.8a,

|F(ω)|≤∫∞−∞|f(t)|dt|F(ω)|≤∫−∞∞|f(t)|dt

By expressing

a+jωa+jω

in the polar form as

a2+ω2−−−−−−√ejtan−1(ωa)a2+ω2ejtan−1(ωa)

,

F(ω)=1a2+ω2−−−−−−√e−jtan−1(ωa)F(ω)=1a2+ω2e−jtan−1(ωa)

Therefore

|F(ω)|=1a2+ω2−−−−−−√|F(ω)|=1a2+ω2

and

θf(ω)=−tan−1(ωa)θf(ω)=−tan−1(ωa)

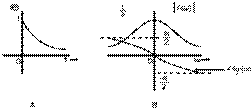

The amplitude spectrum of

|F(ω)||F(ω)|

and the phase spectrum

θf(ω)θf(ω)

are shown in Figure 1.4b. Observe that

|F(ω)||F(ω)|

is an even function of

ωω

, and

θf(ω)θf(ω)

is an odd function of

ωω

, as

expected to be.

As long as condition 1.12 is satisfied,

it shows that the existence of the Fourier transform is assured.

Linearity of the Fourier

Transform

The Fourier transform can be

considered linear if

f1(t)⇔F1(ω)f1(t)⇔F1(ω)

and

f2(t)⇔F2(ω)f2(t)⇔F2(ω)

then,

a1f1(t)+a2f2(t)⇔a1F1(ω)+a2F2(ω)a1f1(t)+a2f2(t)⇔a1F1(ω)+a2F2(ω)

(1.13)

This result can be extended

to any finite number of terms. This proof is trivial and follows exactly from

Eq. 1.8a.

Coming Up

As of now, you should have an

understanding of what an aperiodic signal is and how it is represented by a

Fourier Integral. By applying a limiting process, you should know how an

aperiodic signal can be expressed as a continuous sum over everlasting

exponentials, how the linearity of the Fourier Transform proof is satisfied,

and how to find a Fourier transform using its spectra as well as the conjugate

symmetry property. Next, an understanding of some useful functions, signal

bandwidth, filtering (or interpolating), as well as the synthesis of a

time-limited pulse signal.