The I2C Bus: Hardware

Implementation Details

Essential

information for understanding and designing the hardware needed for an I2C bus.

Sometimes a Little

Complexity Is a Good Thing

The I2C protocol is notable

for some less-than-straightforward characteristics: You don’t just connect a

few IC pins together and then let the low-level hardware take over as you read

from or write to the appropriate buffer, as is more or less the case with SPI

(Serial Peripheral Interface) or a UART (Universal Asynchronous

Receiver/Transmitter). But I2C’s complexity is not without purpose; the rest of

this article will help you to understand the somewhat nuanced hardware

implementation details that make I2C such a versatile and reliable option for

serial communication among multiple independent ICs.

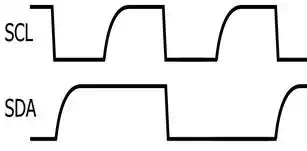

A defining characteristic of

I2C is that every device on the bus must connect to both the clock signal

(abbreviated SCL) and the data signal (abbreviated SDA) via open-drain (or

open-collector) output drivers. Let’s take a look at what this actually means.

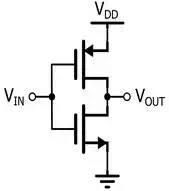

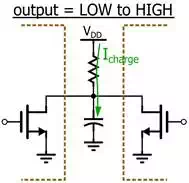

First consider the typical CMOS (inverting) output stage:

If the input is logic high,

the NMOS transistor is on and the PMOS transistor is off. The output thus has a

low-impedance connection to ground. If the input is logic low, the situation is

reversed, and the output has a low-impedance connection to VDD. This is referred to as a push-pull

output stage, though this name is not particularly informative because it does

not emphasize the low-impedance nature of the connections that

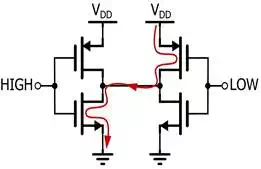

control the output. In general, you cannot directly connect two push-pull outputs

because current will flow freely from VDD to ground if one is logic high and the other is logic low.

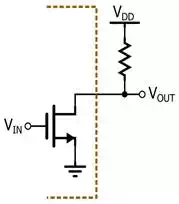

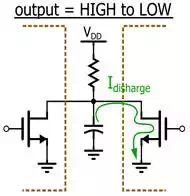

Now consider the open-drain

output configuration:

The PMOS transistor has been

replaced by a resistor external to the IC. If the input is logic high, the NMOS

transistor provides a low-impedance connection to ground. But if the input is

logic low, the NMOS looks like an open circuit, which means that the output

gets pulled up to VDD through

the external resistor. This arrangement leads to two important differences.

First, nontrivial power consumption occurs when the output is logic low,

because current flows through the resistor, through the channel of the NMOS

transistor, to ground (in the push-pull configuration, this current is blocked

by the high impedance of the off-state PMOS transistor). Second, the output

signal behaves differently when it is logic high because it is connected

to VDDthrough a much higher resistance (usually

at least 1 kΩ). This feature makes it possible to directly connect two

(or more) open-drain drivers: even if one is logic low and the other is logic

high, the pull-up resistor ensures that current does not flow freely from VDD to ground.

Here are three important

implications of this open-drain bus configuration:

● The signals always default to logic

high. For example, if an I2C master tries to communicate with a slave device

that has become non-functional, the data signal never enters an undefined

state. If the slave is not driving the signal, it will be read as logic high.

Likewise, if a master device loses power during the middle of a transmission,

the SCL and SDA will return to logic high. Other devices can determine that the

bus is available for new transmissions by observing that both SCL and SDA have

been logic high for a certain amount of time.

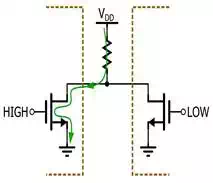

● Any device on the bus can safely drive

the signals to logic low, even if another device is trying to drive

them high. This is the basis of I2C’s “clock synchronization” or “clock

stretching” feature: the master generates the serial clock, but if necessary a

slave device can hold SCL low and thereby decrease the clock frequency.

● Devices with different supply voltages

can coexist on the same bus, as long as the lower-voltage devices will not be

damaged by the higher voltage. For example, a 3.3 V device can communicate with

a 5 V device if SCL and SDA are pulled up to 5 V—the open-drain configuration

causes the logic-high voltage to reach 5 V, even though the 3.3 V device

cannot drive 5 V from a typical push-pull output stage.

If You Have R, You Have RC

The open-drain output driver

is by no means the standard configuration among digital ICs, and with good

reason: it comes with some significant disadvantages. One of these

disadvantages becomes apparent when we recall that capacitance is everywhere.

Voltage changes are constrained by the time required to charge or discharge the

capacitance associated with a particular node. The trouble is, the pull-up

resistors on SCL and SDA limit the amount of charging current—in other words,

we have much more R in the RC time constant that governs the transition from

logic low to logic high.

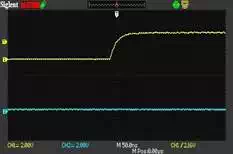

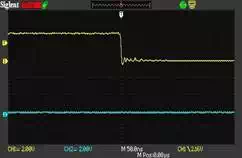

As these diagrams indicate,

the low-to-high transition will be significantly slower than the high-to-low

transition, resulting in the classic I2C “sawtooth”

waveforms:

These two scope captures show

the low-to-high and high-to-low transition for an I2C clock signal with a 1

kΩ pull-up resistor and minimal capacitance (only two devices on the bus,

with short PCB traces).

How to Size the Pull-Up Resistors

At this point it should be

apparent that the pull-up resistance imposes limitations on the maximum clock

frequency of a particular I2C bus. Actually, both resistance and capacitance

are factors here, though we have little control over capacitance because it is

determined primarily by how many devices are on the bus and the nature of the

interconnections between these devices. This leads to the enduring question,

“What value of pull-up resistor should I use?” The trade-off is speed vs. power

dissipation: lower resistance reduces the RC time constant but increases the

amount of current that flows from VDD to ground (through the pull-up resistor) whenever SCL or SDA is

logic low.

The official I2C specification (page 9) states that a voltage is

not considered “logic high” until it reaches 70% of VDD. You may recall that the RC time

constant tells us how long it will take a voltage to reach approximately 63% of

the final voltage. Thus, for simplicity we will assume that R×C tells us how

long it will take the signal to rise from a voltage near ground potential to

the logic-high voltage.

Now how do we find the

capacitance? The “easy” way is to assemble the entire system and measure it; at

least, this is probably easier than trying to perform an accurate calculation

that accounts for every source of capacitance—as an app note from Texas Instruments expresses it, “in the normal

construction of electrical circuits, an unimaginable number of capacitors are

formed.” If the measurement approach is not an option (as is often the case),

you can make a rough estimate by finding the pin capacitance for each device on

the bus (hopefully the datasheet doesn’t let you down here) and then adding 3

pF per inch of PCB trace and 30 pF per foot of coaxial cable (these numbers are

from the same app note, page 3).

Let’s say we have 50 pF of

bus capacitance and we want to obey the I2C “standard mode” specifications,

which state that the maximum rise time is 1000 ns.

trise=1000 ns=(R)(50 pF) ⇒ R=20 kΩtrise=1000 ns=(R)(50 pF) ⇒ R=20 kΩ

So you can satisfy the spec

with Rpull-up = 20 kΩ; this value also

gives you the minimum power consumption. What about speed? Let’s say you want

the clock-high time to be at least triple the rise time.

thigh=3trise=3000 ns ⇒ fmax=12thigh=167 kHzthigh=3trise=3000 ns ⇒ fmax=12thigh=167 kHz

If 167 kHz isn’t fast enough,

you can lower the resistance (at the cost of increased power consumption) until

you reach your desired clock speed. (Actually, “standard mode” limits the clock

speed to 100 kHz, but you can adapt these specs to the needs of your system.)

These are rough calculations,

but honestly, you don’t need to stress out about finding the perfect

resistance. This general approach can help you to settle on a reasonable value,

and you can always swap in different resistors if something isn’t working the

way you want.

Conclusion

If this article has served

its purpose, you are now thoroughly familiar with the salient details involved

in I2C hardware design. We will look at firmware implementation in a separate

article.