Introduction to the I2C

Bus

This article

covers the essential characteristics and prominent advantages of the

Inter–Integrated Circuit (aka I2C) serial-communications protocol.

Communicating via Alphabet Soup

It should come as no surprise

that a common feature of electronic systems is the need to share information

among two or three or ten separate components. Engineers have developed a

number of standard protocols that help different chips communicate successfully—a

fact that becomes apparent when you confront the barrage of acronyms under

“Communications” in the list of features for a microcontroller or digital

signal processor: UART, USART, SPI, I2C, CAN. . . . Each protocol has its pros

and cons, and it is important to know a little about each one so that you can

make an informed decision when choosing components or interfaces.

This article is about I2C,

which is typically used for communications between individual integrated

circuits located on the same PCB. Two other common protocols that also fit into

this general category are UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter)

and SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface). You need to know the basic

characteristics of I2C before you can thoroughly understand a comparison

between these three interfaces, so we will discuss that topic at the end of

this article.

Many Names, One Bus

There is no doubt that the

I2C protocol suffers from a serious terminology problem. The actual name is

Inter–Integrated Circuit Bus. The most straightforward—and probably the least common—abbreviation

is IIC. Perhaps this abbreviation has been disdained because the two capital

I’s look like two 1s, or two lowercase l’s, or roman numeral II, or the symbol

for parallel resistors. . . . In any event, the abbreviation I2C (spoken as “I squared C”) gained

popularity, despite the questionable logic of treating a normal letter as if it

is a variable subject to exponentiation. The third option is I2C (“I two C”),

which avoids the inconvenience of superscript formatting and is also somewhat

easier to pronounce than “I squared C.”

The final layer of fog

settles in when you notice that SMB or SMBus is

apparently used as yet another way of referring to the I2C bus. Actually, these

abbreviations refer to the System Management Bus, which is distinct from,

though almost identical to, the I2C bus. The original I2C protocol was

developed by Phillips Semiconductor, and years later Intel defined the SMBus protocol as an extension of I2C. The two buses

are largely interchangeable; if you are interested in the minor differences

between them, refer to page 57 oftheSystem Management Bus

Specification.

Like Trying to Have an Important Conversation in a Room Full

of People . . .

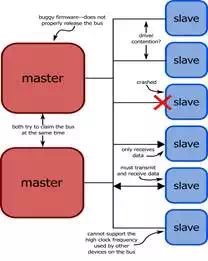

To appreciate the clever

techniques that make I2C so effective, you need to think about the difficulty

of achieving reliable yet versatile communication

between multiple independent components. The situation is simple enough if you

have one chip that is always the master and one chip that is always the slave.

But what if you have multiple slaves? What if the slaves don’t know who the

master is? What if there are multiple masters? What happens if a master

requests data from a slave that for some reason has becomenonfunctional?

Or what if the slave becomes nonfunctional in

the middle of a transmission? What if a master claims the bus to make a transmission

then crashes before releasing the bus?

The point is, there

are a lot of things that can go wrong in this sort of communication environment.

You have to keep this in mind when you are learning about I2C, because

otherwise the protocol will seem insufferably complicated and finicky. The fact

is, this extra complexity is what allows I2C to provide flexible, extensible,

robust, low-pin-count serial communication.

Overview

Before we get into any

details, here are the key characteristics of I2C:

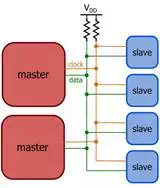

● Only two signals (clock and data) are

used, regardless of how many devices are on the bus.

● Both signals are pulled up to a positive

power supply voltage through appropriately sized resistors.

● Every device interfaces to the clock and

data signal through open-drain (or open-collector) output drivers.

● Each slave device is identified by means

of a 7-bit address; the master must know these addresses in order to

communicate with a particular slave.

● All transmissions are initiated and

terminated by a master; the master can write data to one or more slaves or

request data from a slave.

● The labels “master” and “slave” are

inherently non-permanent: any device can function as a master or slave if it

incorporates the necessary hardware and/or firmware. In practice, though,

embedded systems often adopt an architecture in which one master sends commands

to or gathers data from multiple slaves.

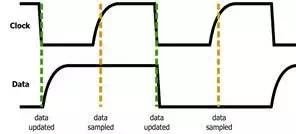

● The data signal is updated on the

falling edge of the clock signal and sampled on the rising edge, as follows:

● Data is transferred in one-byte

sections, with each byte followed by a one-bit handshaking signal referred to

as the ACK/NACK (acknowledge or not-acknowledge) bit.

I2C vs. UART and SPI

The advantages of I2C can be

summarized as follows:

● maintains low pin/signal count even with

numerous devices on the bus

● adapts to the needs of different slave

devices

● readily supports multiple masters

● incorporates ACK/NACK functionality for

improved error handling

And here are some

disadvantages:

● increases the complexity of firmware or

low-level hardware

● imposes protocol overhead that reduces

throughput

● requires pull-up resistors, which

○ limit clock speed

○ consume valuable PCB real estate in

extremely space-constrained systems

○ increase power dissipation

We can see from these points

that I2C is especially suitable when you have a complicated, diverse, or

extensive network of communicating devices. UART interfaces are generally used

for point-to-point connections because there is no standard way of addressing

different devices or sharing pins. SPI is great when you have one master and a

few slaves, but each slave requires a separate “slave select” signal, leading

to high pin count and routing difficulties when numerous devices are on the

bus. And SPI is awkward when you need to support multiple masters.

You may need to

intentionally avoid I2C if throughput is a dominant concern;

SPI supports higher clock frequencies and minimizes overhead. Also, the

low-level hardware design for SPI (or UART) is much simpler, so if you are

working with an FPGA and developing your serial interface from scratch, I2C

should probably be considered a last resort.

Conclusion

We have presented the salient

characteristics of I2C, and we now know enough about the protocol’s pros and

cons to allow for an informed decision on which serial bus you might choose for

a given application. In future articles we will explore the protocol, and how

to actually implement it, in more detail.