Everything You Need to

Know About Direct Digital Synthesis

Introduction

Direct digital synthesis

(DDS) is a technique used to generate an analog signal

(like a sine wave or triangle wave) using digital techniques. The analog signals are synthesized from values stored in

memory. A "template" containing the signal's amplitude values for all

waveform phases is stored in memory and used to recreate the signal. With DDS,

signals can be synthesized directly from the template without requiring the

phase-locked loops other indirect methods require. Different frequencies are

produced by changing the rate the phase values are processed and using

techniques to add, multiply and scale signals, various waveforms can be

generated. The synthesized signals are repeatable and the frequencies precise.

Communication techniques like spread spectrum frequency hopping use DDS to

quickly change frequencies. It is also used for signal generators and enables

frequency sweeps.

Benefits

To understand the benefits of

DDS, consider the situation with radio receivers. If using an analog tuned radio when trying to tune to a specific

station, you adjust whatever knobs, thumb-wheels, and sliders are provided. You

may hit the station exactly one time... but then it may take a while to tune it

in another time. And just because you tuned it once, doesn't mean there isn't

drifting, forcing you to re-tune. When you have a digital tuner, you enter the

station you want and the electronics lock it in.

In the same way, using analog components to generate signals means

adjustments and time to get the frequency correct, without any guarantee the

output will be consistent. DDS with conditioning circuits allow a specific

frequency to be set quickly, consistently, and repeatedly.

DDS has had a big impact in

testing. Before DDS frequency generators, trying to produce accurate frequency

response plots was a frustrating effort. When testing extremely narrow band,

high-order, high-Q filters, when assessing filter

performance over a temperature range, accurate and repeatable frequencies are

required at resolutions that analog generators

can't provide. Some radio frequency (RF) modulation techniques depend on

accurate frequency generation only possible with DDS. When scanning radio frequencies

for signals and power measurements, DDS makes it possible to do RF sweeps

quickly.

The benefits of DDS are:

* The ability to generate

arbitrary frequencies with accuracy and stability, limited only by the

oscillator used to clock the phase accumulator. Crystal oscillators, depending

on their specifications, can deliver tolerances of 50 parts per million to ~0.1

part per billion, making DDS extremely accurate. Analog signal generators can

only deliver accuracy and stability of a few tenths of a percent unless using a

high-end device.

* The frequencies provided by

DDS are repeatable. Loading the tuning word register with the value

corresponding to frequency F1 generates a signal at frequency F1. If the tuning

register is then loaded with the value for frequency F2, the output signal is

quickly changed to frequency F2. When the tuning register is reloaded with the

value for F1, the exact the same frequency F1 is provided as was generated

before. Analog generators can't guarantee this precision.

* High frequency resolution

can be achieved with the digital techniques used in DDS. Increasing the

resolution is as simple as adding more bits to the least significant end of the

phase accumulator and tuning register. Analog waveform generators, which depend

on mechanical components like potentiometers and variable capacitors to tune

the oscillator, are limited in the resolution they can provide.

This ability to quickly

change the output frequency with precision is also essential in communication

techniques like spread-spectrum frequency hopping where radio signals are

transmitted by rapidly switching a carrier among many frequency channels. Being

able to reproduce exact frequencies and deliver frequency changes quickly forms

the basis of the modulation technique.

Synthesizing the Signal

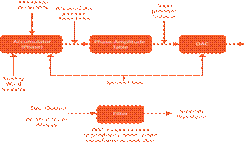

The block diagram for a

representative DDS system is shown in Figure 1.

.

Figure 1

A DDS circuit includes a

phase accumulator, a phase-amplitude table (a lookup table usually in ROM - the

"template") and a digital to analog converter

(DAC). The phase accumulator combines the reference frequency and the value in

the tuning word register. The output from the DAC is usually applied to filters

to smooth the waveform and remove any extraneous output.

The steps to generating a

signal are:

1. The reference signal and

tuning register update the phase accumulator, providing a phase value

2. The corresponding

amplitude for that phase is retrieved from the phase-amplitude table

3. The DAC converts the

retrieved amplitude values to an analog output

4. The output is sent through

smoothing filter

Digital circuits do this

quickly with minimum lag when changing frequencies.

Note: DDS techniques have

been known for some time, but the frequencies that could be provided were

limited by the accuracy of the DAC and the filter (usually a low pass filter with

a capacitor and inductor). With advances in integrated chip technology and

manufacturing, DDS can provide frequencies that are useful for a wide variety

of applications and available on single chip devices. Tools are available to

easily program DDS devices and they can be incorporated into field-programmable

gate arrays (FPGAs). Two popular chips are Analog Devices' AD9833 or AD9850.

Used in a DDS context, the

term reference frequency is used differently than in other engineering

applications. The reference frequency is a clock which controls the rate the

phase accumulator is updated and subsequently the rate the lookup is performed.

Usually provided by a crystal oscillator which clocks the phase accumulator,

some designers use the system clock as the reference. The reference frequency

affects the generated signal; the output is proportional. Doubling the

reference frequency will double the output frequency (when keeping the phase

accumulator, table values and tuning word the same.)

The tuning word is used to

change the output frequencies during operation. The tuning word is a binary

value held in the tuning register. The value of the tuning word is added to the

phase accumulator with every clock update. For example, if the tuning word is

set to 1, every clock interval increments the phase accumulator by 1. Setting

the tuning word to 2, every clock cycle increments the phase accumulator by 2.

Since the phase accumulator

provides the phase value for the phase-amplitude lookup, the tuning word

controls the number of values retrieved from the phase-amplitude table for a

cycle. With a tuning word of 1, every value in the table is retrieved. A tuning

word of 2 reads every other value and also causes the accumulator to clock

through to zero twice as fast, with the result that the output frequency has

been doubled.

As an example, consider a DDS

designed with a phase-amplitude table of 360 entries, holding the amplitude

(voltage) values for each one of the 360 degrees of a sine wave. The

accumulator resets after 360 clock cycles. The reference frequency will be

pulled from the system clock, so everything is clocked and updated at the same

rate. With a tuning word of 1, the phase accumulator is incremented by 1 for

every clock, and the table values are retrieved in order. Every 360 reference

clocks, the accumulator resets and another waveform is created. Setting the

tuning word to 2 has the result of reading every other value from the

phase-amplitude table; the accumulator clocks through twice as fast and the

output frequency is doubled. Of course, using only 360 values would produce a

choppy output and the jitter would make it unusable. DDS systems typically have

phase-amplitude tables with thousands of data points and 16-bit registers for

the tuning register and phase accumulators.

The template values are

important in DDS systems. Just like in digital recording and playback, the

quality of the playback is dependent on the fidelity of the recorded medium and

the playback circuits. No matter how great the playback equipment though, it

can't compensate for a terrible recording. In the same way, a waveform template

used in DDS has to have been digitized (sampled and recorded) to a capture good

signal without distortions.

The templates are built by

digitizing signals using sampling and quantizing techniques and are encoded

into a specific format. The background for digitizing and sampling signals to

be able to recreate them lies in communications theory and how much information

is required to accurately recreate a signal. As communications progressed to

attempting to transmit signals in a digitized format and then recreating

the analog signal at the receiver end, this

became an issue. Harry Nyquist, working at Bell Labs, found that for

band-limited signals (like voice) the sampling rate had to be twice the highest

frequency used to accurately recreate the signal. Sampled at too low a

frequency, the data points might belong to any number of signals at various

frequencies. Sampling at too high a frequency produced more data, taking up

resources but yielding no better results. This frequency is referred to as the

Nyquist Frequency and is the minimum frequency the original signal must be

sampled at to capture enough data points to recreate a specific signal.

Angles and Waveforms

Although DDS can be used to

provide any periodic waveform, like sine, cosine, ramp, and pulse, we'll look

at how a sine wave is synthesized from voltage values stored in memory. Why can

one waveform template produce signals at different frequencies?

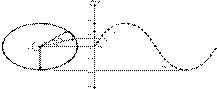

Figure 2a shows a basic

trigonometric phase diagram where a sine wave is shown as a projection from a

circle representing the phase of the waveform. The maximum voltage amplitude

for the sine wave is the radius of the circle. For this discussion, we'll take

the maximum voltage to be one for simplicity. As the phase angle ϴ

advances counterclockwise, there is a

corresponding value of voltage. One complete rotation is 2*Pi radians. No

matter how many times around, the same voltage corresponds the a specific angle ϴ. The frequency of the sine

wave produced depends on how quickly rotations through 2*Pi are completed (the

angular velocity, ω).

Figure 2a.

Phase Diagram

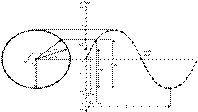

Figure 2b.

Phase Detail

Figure 2b shows how for each

phase, the specific voltage is sampled. The more points provided for the

waveform by the sampling techniques used, the more definition the waveform has.

The phase-amplitude table holds the phase/voltage points for each waveform and

functions as a phase to voltage converter.

Frequency is related to

angular velocity by the formula:

Frequency=angular velocity(ω)2π Frequency=angular velocity(ω)2π

The frequency is the

reciprocal of the period (T) but by using the phase rather than a time-based

measurement to capture voltage values, the repetitive nature of a waveform can

be exploited. The higher the angular velocity (the quicker the rotations of

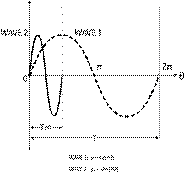

angle ϴ shown in Figure 2a), the higher the frequency. As shown in Figure

3, even though the frequency of a waveform changes, the voltage amplitudes are

the same.

Wave 1 goes though a complete cycle, T, in 2*Pi radians. Wave 2

has a cycle equal to the period of T/4, yielding a frequency four times that of

Wave 1, but the amplitude values for the waveforms are the same. To provide

different frequencies, values from the phase-amplitude table are output in a

given time cycle. Any frequency can be generated depending on how many times

the values in the phase-amplitude table are cycled through in a given time

frame.

Figure 3.

Different Frequencies, Same Values

In the DDS context, the

tuning register and accumulator act to 'simulate' the phase rotation of the

waveform. As the accumulator counts through and resets, another cycle is

generated. Setting the tuning word to higher values clock through the table

quicker to provide higher output frequencies. By changing the tuning word, the

phase increment and therefore the frequency can be quickly changed since

there's no settling time required with DDS.

Issues

As noted above, the

phase-amplitude table is a big part of DDS. If the original waveforms were

sampled at a rate that was too low for a desired frequency, an alias distortion

may be seen in the output, with additional frequency components seen around the

desired frequency or the clock frequency. The sampling rate should be at or

above the Nyquist Frequency. If the sampled frequency can't be raised, extra

filtering may be required to remove excessive outputs.

If the precision of the

accumulator is too low, a jitter may be seen in the output, a result of the

jumping from one point on the waveform to another not being smooth enough.

Using the highest possible precision for the accumulator, tuning register and

phase-amplitude table can help minimize jitter, with filtering and digital

processing techniques used for remaining signal definition.

Summary

DDS provides a way to

generate analog signals from values stored

in memory using digital techniques. By changing a tuning register value,

frequencies can be changed quickly without settling time, making it ideal for

testing, communications and frequency sweep applications.