Migration

Migration is the movement by people from one place to another.

Migration is the physical movement by people from one place to another; it may be over long distances, such as from one country to another, and can occur as individuals, family units, or large groups. When referring to international movement, migration is generally called immigration.

Lee’s laws divide factors causing migrations into two groups of factors: push and pull factors. Push factors are things that are unfavorable about the area that an immigrant is coming from; pull factors are things that attract the immigrant to the new location.Historically, migration has been nomadic, meaning people sustained movement from place to place over their lifetimes. Although only a few nomadic people have retained this lifestyle in modern times, migration continues as both involuntary migration (such as the slave trade, human trafficking, and ethnic cleansing) and voluntary migration within a region, country, or beyond. Specific types of migrants can include colonizers (who forcefully enter into a country or territory), refugees (who are forced to flee their country), and temporary migrants (who travel to a new place temporarily, such as business travelers, tourists, or seasonal farm workers).

Along with fertility and mortality, migration is one of three major variables studied by demographers to measure population change.

Seasonal migration is generally associated with agriculture and tourism. Seasonal agricultural migrants follow crop cycles, moving from place to place to plant or harvest crops. Some countries, including the United States, allow special permits for seasonal agricultural workers to temporarily work in the country without granting full citizenship rights. Seasonal tourists seek out certain natural amenities, like snow-capped mountains for skiing and winter sports or desert sunshine for a break from oppressive winters.

Urbanization refers to migration from rural to urban areas. Since the 1970s, urbanization has become more common in developing countries, where industrialization has made agriculture more efficient and has increased the demand for urban labor. Previously, massive urbanization also took place in developed countries; beginning in Britain in the late eighteenth century, millions of agricultural workers left the countryside and moved to the cities.

Industrialization also sparked transnational labor migration that has further swelled urban populations. In the early twentieth century, transnational labor migration reached a peak of three million migrants per year. During this period, emigration rates were especially high in Italy, Norway, Ireland and the Guangdong region of China.

In the United States, industrialization also led to considerable internal migration (or human migration within a nation) of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North. From 1910-1970, approximately seven million African Americans migrated north to escape both poor economic opportunities and considerable political and social prejudice in the South. They settled in the industrial cities of the Northeast, Midwest, and West, where relatively well-paid jobs were available. This phenomenon came to be known in the United States as the Great Migration.

In many developed countries, urbanization has slowed and the population has begun to move out of cities — in some cases back to rural areas, but most frequently, to newly-built suburbs. The movement from cities to surrounding suburbs is called suburbanization and represents yet another form of internal migration.

Yet another kind of migration, forced migration refers to the coerced movement of a person or persons away from their home or home region. It has been a means of social control under authoritarian regimes, taking the form of ethnic cleansing, slave trades, human trafficking, and forced displacement.

According to neoclassical economic theory, labor migration is motivated primarily by wage differences between two geographic locations. These differences can usually be explained by differences in the supply of and demand for labor. Areas with a shortage of labor but an excess of capital will have a high relative wage, whereas areas with a high labor supply and a dearth of capital will have a low relative wage. Following neoclassical principles, migrants tend to move from low-wage areas to high-wage areas where their labor is in higher demand.

The new economics of labor migration theory criticizes neoclassical economic theory for its narrow focus on individual decisions. According to the new economics theory, migration flows and patterns cannot be explained solely at the level of individual workers and their economic incentives. Instead, wider social entities must be considered as well. One such social entity is the household. Migrants may choose to move in order to reduce the social and economic risk that a household experiences as a result of having insufficient income. The household, in this case, needs extra capital, which can be attained by family members who participate in migrant labor abroad and send money back home as remittances. These remittances can also have a broader effect on the economy of the receiving country as a whole as they bring in capital.

World systems theory looks at migration from a global perspective.It explains that interaction between different societies can be an important factor in social change within societies. Trade with one country, which causes economic decline in another, may create incentives to migrate to a country with a more vibrant economy. It can be argued that even after decolonization, the economic dependence of former colonies still remains.

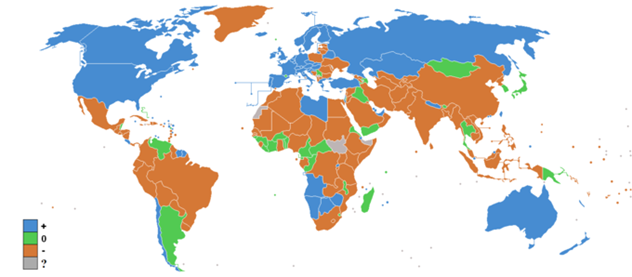

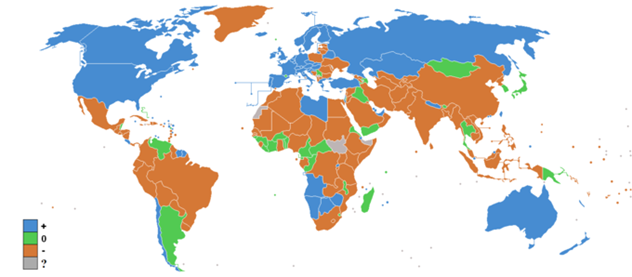

Net Migration Rates by Country: Social, economic, and environmental conditions (such as unemployment, drought, or conflict) can drive large numbers of people to migrate across national borders, as shown by this map. Positive migration rates are indicated in blue; negative migration rates in orange; stable in green; and no data in gray.