Is the U.S. budget deficit sustainable?

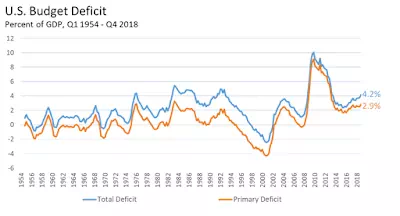

The U.S. federal budget deficit for 2018 came in just shy of $800 billion, or about 4% of the gross domestic product (the primary deficit, which excludes the interest expense of the debt, was about 3% of GDP).

As the figure above

shows, the present level of deficit spending (as a ratio of GDP) is not too far

off from where has been in the 1970s and 1980s. It's also not too far off from

where it was in the early 2000s (although, the peaks back then were associated

with recessions).

Of course, the question people are asking is whether deficits of this magnitude

can be sustained into the foreseeable future without economic consequences

(like higher inflation). In this post, I suggest that the answer to this

question is yes, but just barely. If I am correct, then any new government

expenditure program will have to come at the expense of some other program, or

be funded through higher taxes. Let me explain my reasoning.

The Arithmetic of Government Spending and Finance

I begin with some basic arithmetic (I describe here where theory

comes in). Let G denote government expenditures and

let T denote government tax revenue. Then the primary

deficit is defined as S = G - T ( if S < 0,

then we have a primary surplus ). The absolute magnitudes involved

have little meaning--it turns out to be more useful to measure a growing

deficit relative to the size of a growing economy. Let Y denote the

gross domestic product (the total income generated in the economy). The

deficit-to-GDP ratio is then given by (S/Y). In what follows, I will

assume that this ratio is expected to remain constant over the indefinite

future (this is what a "sustainable" budget deficit means.)

Let D denote the outstanding stock of government "debt."

For countries that issue debt representing claims to their own currency and

permit their currency to float in foreign exchange markets, attaching the label

"debt" to these objects--like U.S. Treasury securities--is somewhat

misleading. The better analog in this case is equity. Companies that finance acquisitions

or expenditure through equity do not have to worry about bankruptcy. They may

have to worry about diluting the value of existing shareholders if they

over-issue equity, or use it to finance negative NPV projects. The same is true

of the U.S. federal government (but not state or local governments). The risk

of over-issuing treasury debt is not default--it is share dilution (i.e.,

inflation).

Let R denote the gross yield on debt (so that R -

1 is the net interest rate). If we interpret D as

currency, then R = 1 (currency has a zero net yield). If we

interpret D as U.S. Treasury debt, then R = 1.025 (UST debt

has an average net yield of around 2.5%). Note that in some jurisdictions

today, government debt has a negative yield (so, R < 1 )

-- that is, government "debt" is in this case an income-generating

asset!

Alright, back to the arithmetic. Let D' denote the stock of debt

inherited from the previous period that is due interest today. The interest

expense of this debt is given by (R - 1)D' (the interest expense of

currency is zero). The primary deficit plus interest expense must be financed

with new debt D - D', where D represents the stock of debt today

and D' represents the stock of debt yesterday. Our simple arithmetic

tells us that the following must be true:

[1] S + (R - 1)D' = D - D'

Let me rewrite [1] as:

[2] S = D - RD'

Now, let's divide through by Y in [2] to get:

[3] (S/Y) = (D/Y) - R(D'/Y)

We're almost there. Notice that (D'/Y) = (D'/Y')(Y'/Y). [I want to say

that this is just high school math...except that my son came to me the

other night with a homework question I could not answer. If you're not good at

math, I understand your pain. But if you need some help, don't be afraid to ask

someone. Like my son, for example.]

Define n = (Y/Y'), the (gross) rate at which the nominal GDP grows over

time. In my calculations below, I'm going to assume n = 1.05, that is 5%

growth. Implicitly, I'm assuming 2-3% real growth and 2-3% inflation, but I

don't think what I have to say below depends on what is driving NGDP growth. In

any case, let's combine (D'/Y) = (D'/Y')(Y'/Y) and n =

(Y/Y') with [3] to form:

[4] (S/Y) = (D/Y) - (R/n)(D'/Y')

One last step: assume that the debt-to-GDP ratio remains constant over time;

i.e., (D'/Y') = (D/Y). Again, I impose this condition to

characterize what is "sustainable." Combining this stationarity

condition with [4] yields:

[*] (S/Y) = [1 - R/n ](D/Y)

Condition [*] says that the deficit-to-GDP ratio is proportional to the the

debt-to-GDP ratio, with the factor of proportionality given by [1 - R/n

]. This latter object is positive if R < n and negative

if R > n.

The Mainstream View

There is no such thing as "the" mainstream view, of course. But I

think it's fair to say that in thinking about the sustainability of government

budget deficits, many economists implicitly assume that R > n. In this

case, condition [*] says that if the outstanding stock of government debt is

positive (D > 0), then sustainable deficits are impossible. Indeed, what is

needed is a sustainable primary budget surplus to service the

interest expense of the debt.

The condition R > n is a perfectly reasonable assumption for any

entity that does not control or influence the money supply: state and local

governments, emerging economies that issue dollar-denominated debt, EMU

countries that issue debt in euros, federal governments that abide by the gold

standard or delegate control of the money supply to an independent central bank

with a preference for tight monetary policy.

The only exception to this that a mainstream economist might make is for the

case of "debt" in the form of currency. The seigniorage revenue

generated by currency (zero-interest debt), however, is typically considered to

be small potatoes. Consider the United States, for example. Let's

interpret Das currency. Currency in circulation is presently around $1.7

trillion, almost 10% of GDP. So let's set (D/Y) = 0.10, R = 1,

and n = 1.05 in equation [*]. If I've done my math correctly, I

get (S/Y) = 0.0025, or (1/4)% of GDP. That's about $100 billion. This

may not sound like "small potatoes" to you and me, but it is for a

government whose expenditures in 2018 totaled about $4 trillion.

The New and Modern Monetarist View

I think of "monetarists" as those who view money and banking as critical

factors in determining macroeconomic activity. I'm thinking, for example, of

people like Friedman, Tobin, Wallace, Williamson and Wright (old and

new monetarists) on the mainstream side and, for example, Godley, Minksy, Wray,

Fullwiler on the MMT (and other heterodox) side. A common ground

shared by new/modern monetarists is the view of treasury debt as a form of

money; i.e., the difference between (say) U.S. Treasury debt and Federal

Reserve money is more of degree than in kind. Consider, for example, the

following two objects:

Can you spot the

difference? The first one was issued by the U.S. Treasury and the second

one by the Federal Reserve (the promised redemption for silver has long since

been suspended). The Fed is said to "monetize the debt" when it

replaces the top bill with the bottom bill. Is it any wonder why the BoJ cannot

create inflation by swapping zero-interest BoJ reserves for zero-interest JGBs?

(In case you're interested, see my piece here.)

In any case, rightly or wrongly, U.S. government policy presently renders the

treasury bill illiquid (in the sense that it cannot easily be used to make

payments). Of course, while the treasury bill no longer exists in physical

form, every U.S. person can acquire the electronic version of (interest-bearing)

T-bills at www.treasurydirect.gov. Just don't expect to be able to pay

your rent or groceries with your treasury accounts any time soon. (Though, as I

have argued elsewhere, it would be a simple matter to integrate treasury direct

accounts with a real-time gross settlement payment system.)

But even if treasury securities cannot be used to make everyday payments, they

are still liquid in the sense of being readily convertible into money on

secondary markets (and maybe one day, on a Fed standing repo facility, as Jane

Ihrig and I suggest here and here). USTs are used widely as

collateral in credit derivative and repo markets -- they constitute a form of

wholesale money. Because they are safe and liquid securities, they can trade at

a premium. A high price means a low yield and, in particular, R <

n is a distinct possibility for these types of securities.

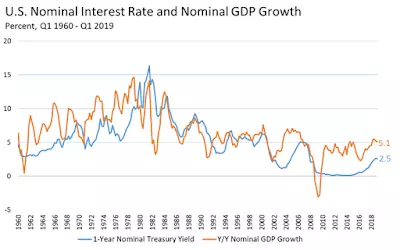

In fact, R < n seems to be the typical case for the United States.

The only exception in

this sample is in the early 1980s -- the consequence of Volcker's attempt to

reign in inflation.

But if this is the case, then the mainstream view has long neglected a source

of seigniorage revenue beyond that generated by currency. Low-yielding debt can

also serve as a revenue device, as made clear by condition [*] above. How much

is this added seigniorage revenue worth to the U.S. government?

Let's do the arithmetic. For the United States, the (gross) debt-to-GDP ratio

is now about 105%, so let's set (D/Y) = 1.0. Let's be optimistic

here and assume that the average yield on USTs going forward will average

around 2%, so R = 1.02. As before, assume NGDP growth of 5%, or n =

1.05. Condition [*] then yields (S/Y) = 0.03, or 3% of GDP. That's

about $600 billion.

$600 billion is considerably more than $100 billion, but it's still small

relative to an expenditure of $4 trillion. And, indeed, since the budget

deficit is presently running at around $800 billion, there seems little scope

to increase it without inducing inflationary pressure. (Note: by "increase

it" I mean increase it relative to GDP. In the examples above, the

debt and deficit all grow with GDP at 5% per year).

Conclusion

What does this mean for fiscal policy going forward? The main conclusion is

that the present rate of deficit spending and high level of debt-to-GDP is not

something to be alarmed about (especially with inflation running below 2%). The

national debt can, will, and probably should continue to grow indefinitely

along with the economy. What matters more is how expenditures are directed and

how taxes are collected. Of course, this should be done with an eye to keeping

long-term inflation in check.

What deserves our immediate attention, in my view, is a re-examination of the

mechanisms through which government spending (when, where and how much) is

determined. This is not the place to get into details, but suffice it to say

that one should hope that our elected representatives have a capacity to reason

effectively, have a broad understanding of history, are willing to listen, and

do not view humility and compromise as four-letter words or signs of personal

weakness. If we don't have this, then we have much deeper problems to deal with

than the national debt or deficits.

Once the spending priorities have been established, the question of finance

needs to be addressed. If the level of spending is less than 2% of GDP, then

explicit taxes can be set to zero--seigniorage revenue should suffice. However,

if we're talking 20% of GDP then tax revenue is necessary (at least, if the

desired inflation target is to remain at 2%). If the tax system is inefficient

and cannot be changed, this may mean cutting back on desired programs. Ideally,

of course, the tax system could be redesigned to minimize inefficiencies and

distortions. But tax considerations are likely always to remain in some form

and, because this is the case, they should be taken into consideration when

evaluating the net social payoff to any new expenditure program.