What is “average inflation targeting”?

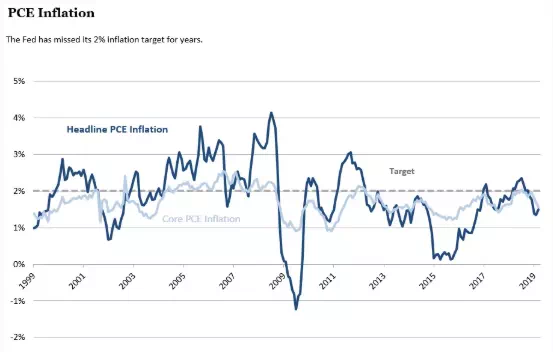

he Federal Reserve is charged by Congress with maintaining price stability and maximum sustainable employment. The Fed defines “price stability” as inflation at 2 percent. In its last annual statement on its goals and monetary policy strategy, the Federal Open Market Committee—the Fed’s policy-making body—said: “Inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate. The Committee would be concerned if inflation were running persistently above or below this objective.”

The groundwork to declare an inflation target and set it at 2 percent was laid in the 1980s when central banks around the world were eager to bring down inflation—then well above 2 percent—and saw advantages in adopting a clear, well-defined, and public objective. In 1996, when inflation was running at about 3 percent, Fed officials reached a rough consensus behind closed doors that 2 percent was a good definition of price stability. In 2012, the Fed made 2 percent the official, public target.

The Fed uses forecasts of inflation relative to the 2 percent target, along with measures of unemployment and other economic indicators, to help decide whether to raise or lower short-term interest rates. Under this framework, the Fed aims at 2 percent inflation in the future, and doesn’t compensate for periods where inflation is either above or (more relevant recently) below 2 percent. It lets bygones be bygones. (For more on the 2 percent target and alternatives to it, see “Rethinking the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target,” a report on a Hutchins Center January 2018 conference.)

The Fed is now conducting a review of its monetary policy strategy, tools, and communications practice. That review will not consider changing the Fed’s statutory mandate nor will it consider changing the 2 percent inflation objective. “It will,” the Fed says, consider whether the Fed can best meet its mandate “with its existing monetary policy strategy, whether the existing monetary policy tools are adequate to achieve and maintain the dual mandate, and whether the communications about the policy strategy and tools can be improved.”

WHAT PROMPTED THE FED TO EVALUATE THIS FRAMEWORK?

One, inflation has been mostly below the 2 percent target for several years.

Two, there is widespread agreement that the neutral interest rate— the short-term real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate consistent with an economy operating at full employment with low and stable inflation – has fallen over the past couple of decades. In the 1990s, a typical estimate of the neutral rate was 2 percent or 2.5 percent. Today, Fed officials put it somewhere between 0.5 percent and 1.5 percent.

Add an inflation rate of 2 percent to that real neutral rate, and the nominal neutral rate is somewhere between 2.5 percent and 3.5 percent. That doesn’t give the Fed much room to cut interest rates by 4 or 5 percentage points as it often does in recessions. A persistently low neutral rate suggests that the Fed is likely to bump against the “zero lower bound” more often in the future than it has in the past. Once nominal rates hit zero, the Fed may not be able to cut real interest rates as much below zero as it usually does to spur borrowing and pull the economy out of recession. (At 2 percent inflation, a zero nominal interest rate is a minus 2 percent real rate.) Central bankers pay close attention not only to measures of current inflation, but also to inflation expectations. When inflation expectations are “well anchored,” as central bankers put it, the Fed can do a better job steering the economy through periods at which, for instance, oil prices rise or fall sharply; consumers, businesses, and markets will behave as if the Fed will keep inflation stable even if there are occasional ups and downs.