Female Economists Push Their Field Toward a #MeToo Reckoning

ATLANTA — The economics profession is facing a mounting crisis of sexual harassment, discrimination and bullying that women in the field say has pushed many of them to the sidelines — or out of the field entirely.

Those issues took center stage at the American Economic Association’s annual meeting, the largest gathering of the profession, last weekend in Atlanta. Spurred by substantiated allegations of harassment against one of the most prominent young economists in the country, top women in the field shared stories of their own struggles with discrimination. Graduate students and junior professors demanded immediate steps by the A.E.A. to help victims of harassment and discipline economists who violate the group’s newly adopted code of conduct.

Leading male economists offered an unprecedented acknowledgment of harassment and discrimination in the field. “Economics certainly has a problem,” Ben Bernanke, the former Federal Reserve chairman, who took over as A.E.A. president this year, said during a panel discussion. The profession has, “unfortunately, a reputation for hostility toward women and minorities,” he said.

Janet L. Yellen, who was the first chairwoman of the Fed and will head the A.E.A. next year, said that addressing the issue “should be the highest priority” for economists in the years to come.

During a panel discussion on gender issues, Ms. Yellen was one of several women who shared stories of discrimination and bullying. Her fellow panelists described a list of “known” male predators in academic departments who have never been punished for behavior that included repeatedly making unwanted sexual advances toward junior colleagues.

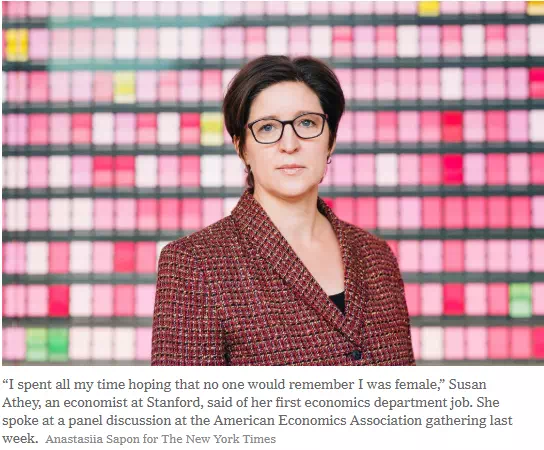

One of the panelists, Susan Athey, a Stanford economist, said she had bought “khakis and loafers” to fit in with the men in the lunchroom of her first economics department, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She did so even though the department was the “most supportive environment” she has encountered in her career.

“I spent all my time hoping that no one would remember I was female,” said Ms. Athey, a past winner of a prestigious award for young economists. “I didn’t want to remind people that I’m a sexual being.”

Economics has long struggled with diversity. Only about a third of economics doctorates go to women, and the gender gap is wider at senior levels of the profession. Racial and ethnic minorities — particularly African-Americans and Latinos — are even more underrepresented. And notably, the gender gap in economics is wider than in other social sciences and, at least by some measures, traditionally male-dominated fields such as science and math.

Certain subfields, like finance, have a particularly poor record of advancing women. A branch of the American Finance Association presented survey results in Atlanta that show barely 10 percent of tenured finance professors, and 16 percent of tenure-track faculty, are women. In economics as a whole, women accounted for about 23 percent of tenured and tenure-track faculty in 2015.

Stories of harassment and discrimination, long shared in private conversations and email chains, began to be aired more publicly last year with allegations that Roland G. Fryer, a prominent Harvard economist, had harassed and bullied women in his university-affiliated research lab. The New York Times reported last month that a Harvard investigation had substantiated some of those claims while other investigations are continuing.

The economics association last year approved its first code of professional conduct, which calls for “equal opportunity and fair treatment for all economists” regardless of sex, race or other characteristics. The association also created a standing committee to address diversity, and is surveying its members about harassment and discrimination.

But many economists, particularly younger ones, pushed leaders here for more aggressive action. Hundreds of graduate students and research assistants have signed an open letter calling for more explicit codes of conduct, stronger enforcement and better systems for reporting abuses, among other reforms.

“We shouldn’t have to rely on whisper networks to protect us from abuse and inappropriate behavior,” they wrote. “And we don’t have the power to discipline our supervisors, or even our peers. You do. Please, listen to us.”

Some of that frustration bubbled over in the A.E.A.’s formal business meeting Friday evening, a usually dry affair in which members hear reports on the association’s finances and similar matters.

“There’s just a ton of anger and resentment around how the profession has been,” Elisabeth Perlman, 34, an economist with the Census Bureau, said at the meeting. She added that the profession must also address the misconduct that was allowed to go unchecked for decades.

Meeting attendees also expressed frustration with what they said was the association’s response to the allegations against Mr. Fryer, who had been due to join the A.E.A.’s executive committee this month. After the Times article was published, the association issued a two-sentence announcement that Mr. Fryer had resigned, but made no other public statement.

“The silence from the executive committee has really been deafening,” Jennifer Doleac, a professor at Texas A&M, said at Friday’s business meeting. “A lot of the profession is really waiting to hear from you, and for some semblance of leadership about the direction of the profession and what will be tolerated and what won’t be.”

Olivier Blanchard, the association’s departing president, said for the first time Friday that the executive committee had asked Mr. Fryer to resign. He called that request “the best way out” because the association had no formal procedure to remove an elected officer. The committee, Mr. Blanchard said, is now working to develop such rules.

Some members of the executive committee wanted to go further and establish procedures to punish or expel members for violations of the code of conduct. There are currently no such penalties.

Other members seemed more skeptical of that idea when it was raised in a closed-door session last Thursday, according to several people who were there. Mr. Blanchard cut off discussion, saying he was hungry and it was time for lunch, these people said. The committee will take up the issue again in April.

Mr. Blanchard, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, did not dispute that account. “The job of the person in charge of the meeting is to make sure that all issues on the agenda are taken up and discussed,” he wrote in an email on Wednesday, adding a parenthetical: “and yes, that people, including me, have time to eat.”

He also said that he was “happy” that the profession was taking women’s concerns seriously, and that “I think the A.E.A. is playing a strong role” on the issue.

Lisa D. Cook, a Michigan State University economist who is one of the most prominent black women in the field, credited younger women with forcing the A.E.A. to move more quickly.

“I told them they have more power than they know,” Ms. Cook said of graduate students and other young people pushing for change. “This is the possible beginnings of a sea change.”

Many male economists long dismissed claims of bias and discrimination, arguing that gender disparities must reflect differences in preference or ability. They pointed to theories that predict that, in the simplified world of economic models, discrimination on the basis of characteristics like gender and race would disappear because of competition.

In recent years, however, a growing body of research has found evidence of discrimination at virtually every stage of the profession, from undergraduate enrollment to tenure decisions. Erin Hengel, a University of Liverpool economist, has found that women are held to higher standards of writing and research than their male colleagues. Alice Wu, then an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley, made waves two years ago with a paper documenting rampant misogyny and hostility toward women on a popular online forum for graduate students.

One provocatively titled paper presented in Atlanta asked “Does Economics Make You Sexist?” It found that undergraduate students in Chile exhibited more implicit and explicit gender bias after studying economics. The effect was particularly strong among male students — and weaker in departments with more female faculty members.

Shelly Lundberg, a University of California, Santa Barbara, economist who has long pushed the field to include more women, said that each study had faced “an unusual level of scrutiny and skepticism,” but that taken together, they were hard to dismiss.

“The realization that this is real, that there is bias, is starting to sink in,” Ms. Lundberg said. “I really think this may have been the breakthrough.”