Banking integration in the EMU: Let’s get real!

As the euro approaches its 20th birthday, it has been a catalyst for banking integration among its members, but this integration has remained incomplete. The euro has created an integrated European interbank market, but not ‘deep’ or ‘real’ cross-border banking integration. Bank-to-bank lending has surged between euro area countries but direct cross-border lending of banks to the real sector, cross-border branching, and cross-border consolidation of banks have not.

This lopsided banking integration in the EMU had real consequences during the Great Recession. Real outcomes in crisis-hit countries were worse than they would otherwise have been, and there was a breakdown in macroeconomic risk-sharing at the precise moment it was urgently needed.

Europe's great retrenchment

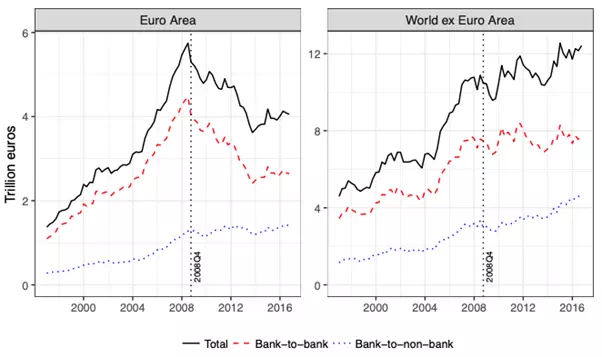

Figure 1 illustrates this pattern of banking integration. After 1999, there was a surge in cross-border interbank lending among euro area countries that quickly reversed during the crisis. In contrast, cross-border lending of banks to the real (non-bank) sector increased much less before 2008, but remained remarkably stable during the crisis. Allen et al. (2011) and Emter et al. (2018) have pointed out that this `great retrenchment’ in cross-border interbank integration was specific to Europe. The right-hand panel of Figure 1 shows that interbank lending among non-EMU industrialised countries did not suffer a setback during the crisis.

Figure 1 Cross-border bank lending in the euro area and other advanced countries

Source: Hoffmann et al. (2018), based on BIS locational banking

statistics database.

Notes: The figure plots

cross-border lending by foreign banks to 19 euro area economies (euro area) and

a sample of 118 other advanced and developing countries (world ex euro area).

The black solid line shows total lending, the red dashed line shows lending by

foreign banks to domestic banks, and the blue dotted line shows lending by

foreign banks to the domestic non-bank sector (including governments). All

values are in trillions of euros.

Domestic bank dependence

We argue that the situation in the euro area today is reminiscent of banking in the US pre-1980, where there was a common interbank market but little deep interstate banking integration due to restrictive banking laws. The removal of barriers to entry for out-of-state banks considerably improved access to finance, in particular for small firms, and contributed to higher growth, lower state-level business cycle volatility (Jayaratne and Strahan 1996, Morgan et al. 2004, Rice and Strahan 2010, Kroszner and Strahan 2014), and better and more resilient interstate risk-sharing (Demyanyk et al. 2007, Hoffmann and Shcherbakova-Stewen 2011).

In Europe today there are no formal barriers to entry for banks from other member countries, but there are many de facto barriers to cross-border branching or to the cross-border consolidation of banks. These include the absence of a common resolution mechanism for banks, the absence of a common deposit insurance scheme, and the tendency of national governments to promote domestic banks as ‘national champions’.

We argue that these barriers lead to a lack of real, direct banking integration in the euro area. This created high macroeconomic costs during the global crisis.

In Hoffmann et al. (2018a), we show that, across the EMU, sectors with many small firms were particularly dependent on the domestic banking system for credit, making them exposed to the collapse in cross-border interbank lending during the financial crisis.

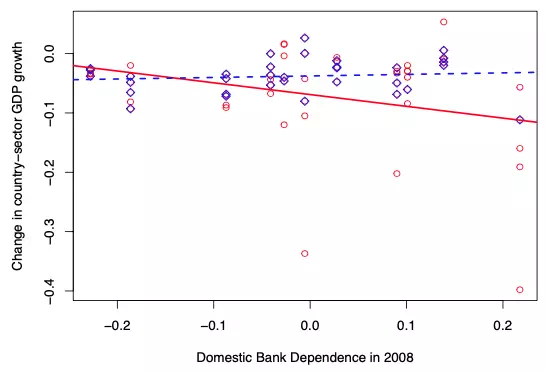

Figure 2 illustrates the main empirical findings from this paper. It plots the drop in GDP growth for more than 60 country-sectors in 11 EMU countries against the share of domestic credit to the real sector originated by domestic banks (‘domestic bank dependence’). While there is essentially no link between post-2008 sector-level growth and domestic bank dependence for sectors with below median shares of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), there is a significantly negative link for the high-SME sectors.

Figure 2 Post-2008 sector-level growth and domestic bank dependence: Sectors with low versus high SME shares

Source: Hoffmann et al. (2018a).

Notes: The graph plots

the change in output from pre-2008 to post-2008 average growth rates at the

country-sector level against the average pre-2008 level of domestic bank

dependence in each country. Blue (red) diamonds (circles) indicate sectors in

countries with below (above) median SME shares. The blue, dashed (red, solid)

lines indicate the regression relationship between growth and domestic bank

dependence for the sample of blue (red) diamonds (circles). The observation

period is 1999-2013 for the 11 EMU countries Austria, Belgium, Finland, France,

Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain.

Our results suggest that the EMU economies most severely hit by the crisis – notably Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Italy – were the ones with the highest levels of domestic bank dependence and the highest shares of SMEs. The high levels of domestic bank dependence ultimately exposed these economies to the collapse in interbank lending, with particularly adverse effects due the high prevalence of bank-dependent small firms.

The lack of real banking integration contributed to low output growth in the countries most affected by the crisis. Our companion paper (Hoffmann et al. 2018b) illustrates also that the lack of real banking integration further contributed to a high pass-through of output declines to household consumption.

The benefits of risk sharing

The ability of households or entire countries to shield their consumption from fluctuations in output is often referred to as risk sharing. Financial markets play a key role in sharing risk because they allow firms to distribute good and bad output shocks across countries, so that (positive or negative) financial returns partly go to stakeholders in other countries. Despite a recent push towards capital market union, the level of financial integration in the euro area still lags far behind the level between US states (Hoffmann and Sørensen 2012). Government and consumers can further soften income fluctuations through counter-cyclical borrowing and lending, but the ability to keep consumption stable in a recession ultimately depends on the continued availability of credit, and so the nature of banking integration matters.

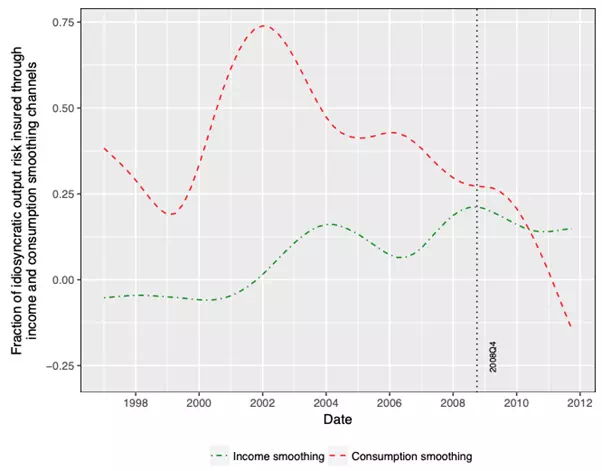

Figure 3 illustrates how risk sharing between EMU countries evolved over the first 10 years of the euro, and during the financial crisis. The vertical axis shows the fraction of output risk that is shared in the two broad channels of risk-sharing (with total risk-sharing being the sum of the two): the green line measures risk sharing through cross-border flows of capital income – usually referred to as income smoothing – while the red line focuses on consumer’s ability to smooth consumption given income, using saving and dissaving or access to consumer credit. This channel is generally referred to as consumption smoothing.

Figure 3 Income and consumption smoothing in the euro area, 1997-2013

Source: Hoffmann et al. (2018b).

Notes: The figure plots

the degree of income smoothing (green line) and consumption smoothing (red

line) for the euro area economies from the first quarter of 1997 to the fourth

quarter of 2013.

The figure shows that there is a marked decline in consumption smoothing during the financial crisis, while income smoothing remains stable. Direct banking integration is associated with better income smoothing, while interbank integration, exactly because it is unstable in periods of financial stress, is a key factor behind the fall in consumption smoothing – and thus risk sharing overall – during the crisis.

So we conclude that crisis periods, interbank integration does not provide the same level of benefits as more direct forms of banking integration. Compared to direct banking integration it increases the exposure of local banking sectors to global banking shocks. At the same time, it does not lessen the impact of local banking shocks on the domestic economy.

From model simulations, we find that countries with high domestic banking dependence and an economy dominated by SMEs would be particularly vulnerable to crises whether they occurred due to local shocks (such as sovereign-bank doom loops or bursting housing bubbles) or global banking shocks. Interbank integration does not insulate the domestic economy against either form of shock.