The Consumer

Consumer : A person who is capable of choosing a president but incapable of choosing a bicycle without help from a government agency. ˝Herbert Stein, Washington Bedtime Stories (1979)

It is now time to introduce the second of the principal economic actors in the economic system ˝the consumer. In a sense this is the heart of the microeconomics. Why else speak about ýconsumer sovereigntyţ? For what else, ultimately, is the economyÝs productive activity organised? We will tackle the economic principles that apply to the analysis of the consumer in the following broad areas:

áAnalysis of preferences.

Consumer optimisation in perfect markets.

ConsumerÝs welfare.

This, of course, is just an introduction to the economics of individual consumers and households; in this chapter we concentrate on just the consumer in isolation. Issues such as the way consumers behave en masse in the market, the issues concerning the supply by households of factors such as labour and savings to the market and whether consumers ýsubstituteţ for the market by producing at home are deferred until chapter 5. The big topic of consumer behaviour under uncertainty forms a large part of chapter 8. In developing the analysis we will see several points of analogy where we can compare the theory of consumer with the theory of the Írm. This can make life much easier analytically and can give us several useful insights into economic problems in both Íelds of study.

The consumerÝs environment

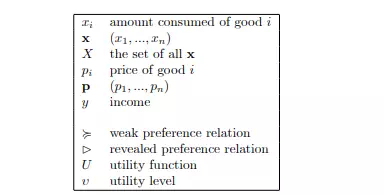

As with the Írm we begin by setting out the basic ingredients of the problem. First, a preliminary a word about who is doing the consuming. I shall sometimes refer to ýthe individual,ţ sometimes to ýthe householdţ and sometimes ˝more vaguely ˝ to ýthe consumer,ţ as appropriate. The distinction does not matter as long as (a) if the consumer is a multiperson household, that householdÝs membership is taken as given and (b) any multiperson household acts as though it were a single unit. However, in later work the distinction will indeed matter ˝see chapter 9. Having set aside the issue of the consumer we need to characterise and discuss three ingredients of the basic optimisation problem:

the commodity space;

the market;

motivation.

Revealed preference

We shall tackle Írst the dió cult problem of the consumerÝs motivation. To some extent it is possible to deduce a lot about a ÍrmÝs objectives, technology and other constraints from external observation of how it acts. For example from data on prices and on ÍrmsÝ costs and revenue we could investigate whether ÍrmsÝinput and output decisions appear to be consistent with proÍt maximisation. Can the same sort of thing be done with regard to consumers? The general approach presupposes that individualsÝor householdsÝactions in the market reßect the objectives that they were actually pursuing, which might be summarised as ýwhat-you-see-is-what-they-wantedţ.

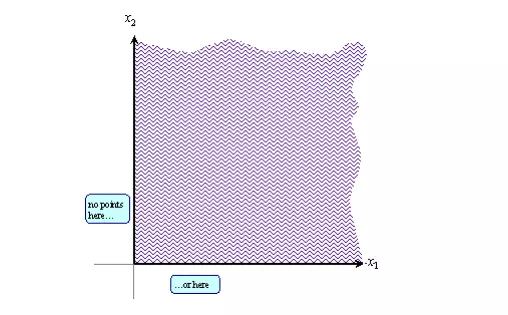

You can get a long way in consumption theory with just this. Indeed with a little experimentation it seems as though we are almost sketching out the result of the kind of cost-minimisation experiment that we performed for the Írm, in which we traced out a portion of a contour of the production function. Perhaps we might even suspect that we are on the threshold of discovering a counterpart to isoquants by the back door (we come to a discussion of ýindižerence curvesţ on page 77 below). For example, examine Figure 4.4: let x B x 0 , and x 0B x 00 , and let N(x) denote the set of points to which x is not revealed-preferred. Now consider the set of consumptions represented by the unshaded area: this is N(x) \ N(x 0 )\N(x 00) and since x is revealed preferred to x 0 (which in turn is revealed preferred to x 00 we might think of this unshaded area as the set of points which are ˝ directly or indirectly ˝ revealed to be at least as good as x 00: the set is convex and the boundary does look a bit like the kind of contour we discussed in production theory. However, there are quite narrow limits to the extent that we can push the analysis. For example, it would be possible to have the following kind of behaviour: x B x 0 , x 0 B x 00 , x 00B x 000 and yet also x 000 B x. To avoid this problem actually you need an additional axiom ˝the Strong Axiom of Revealed Preference which explicitly rules out cyclical preferences.