Monopoly and pricing

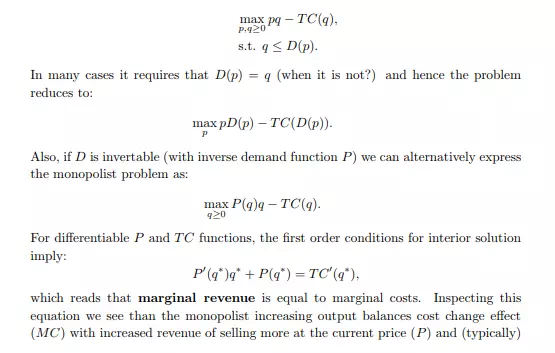

A monopoly is a firm with market power, i.e. it observes impact of own quantity change on the market price. Hence we say that monopoly is a price maker. Observe that in order to determine, whether a company is a monopolist or not, one needs an appropriate definition / boundaries of a market. Monopolists face two constraints: technological summarized by a cost function T C, and market summarized by demand D. The problem of monopolists is to choose price and quantity to maximize profits under these two constraints:

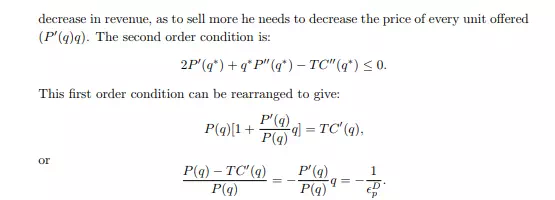

The right hand side term is a (minus) inverse of price elasticity of demand and gives the simple rule for monopoly pricing. The left hand side is sometimes referred to as the Lerner index, measuring the % of price that finances markup (difference between price and marginal costs). Also, it follows that at the optimal level of quantity the price elasticity of demand must be greater than one in absolute values. To challenge your thinking try to analyze the following case. Suppose marginal costs of production increase as a result of technological change, or market regulations. When is it a case that the monopoly will increase its absolute markup? How about its relative markup? We now present few examples or deriving the optimal monopoly price:

interior choice of l ∗ is pf0 (l ∗ ) = w(l ∗ ) + w 0 (l ∗ )l ∗ or rewriting w(l ∗ )−pMPL w(l ∗) = − 1 L w , where L w is a wage elasticity of labor supply. Observe that mixed cases are also possible allowing for company that has market power at both the input and output markets for example. Typically P 0 (q) < 0 and together with increasing marginal costs, a monopoly pricing rule implies that monopolist would produce less than a perfectly competitive firm. It also implies higher prices set by monopolist. This indicates that monopolistic solution is not socially efficient. To see that clearly, consider a single consumer economy with quasilinear utility u(x)+y giving an inverse demand function p(x) = u 0 (x). There is also a monopolist with differentiable cost function T C. The social objective is to maximize W(x) := u(x)−T C(x) which gives the first order condition u 0 (x ∗ ) = p(x ∗ ) = MC(x ∗ ). On the other hand the monopolist chooses p(xm) + p 0 (xm)xm = MC(xm) and hence W0 (xm) = u 0 (xm) − MC(xm) = −p 0 (xm)xm = −u 00(xm)xm > 0 if u 00 is negative. The inefficiency of a monopoly is sometimes called a deadweight loss. The next question we consider is: why (generally inefficient) organizations as monopolists are present in the market.

The starting point concerns the so called natural monopolies. That is the case, where a single firm is more efficient (has lower average costs for all production levels at which inverse demand is higher than average costs), than two or more firms operating separately. The typical example is a company with decreasing average costs function that is characterized by economies of scale for all relevant output levels (i.e. output levels such that inverse demand is higher than average costs). More generally there are barriers to entry that restrict new companies to enter the market and to challenge the monopolist. Following a classification introduced by Bain we consider structural and strategic barriers to entry. Structural barriers to the entry exist, when incumbent firms have cost or demand advantages that would make it unattractive for a new firm to enter the industry. One reason for that could be some form of technological effects, like natural monopoly, but it may also include some legal regulations making it very costly to enter.

Alternatively strategic barriers to entry include incumbent firm taking explicit steps to deter the entry. The examples include limit pricing (decreasing own price to signal low markups and deter entry), increasing production to move down the experience curve (learning-by-doing effect), deliberately increasing customers’ switching costs or developing networking effects via lowering costs of within network consumption. Although inefficient a monopoly makes a higher profit, than a perfectly competitive firm, hence monopolistic firms often engage in rent-seeking activities to protect their market power and increase profit (fortunately not always at the costs of efficiency) (see Stigler (1971) for an early introduction to the economics of regulation or Pepall, Richards, and Norman (2008) for some more recent developments).