Introduction to economic methods

A traditional definition of economics, advocated by Lionel Robbins, says that Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses. Resources are typically limited but needs need not be, hence economists analyze trade-offs how to allocate their constrained resources towards alternative uses. The typical questions that can be addressed within this framework are: what goods and services to produce, how to produce them efficiently, how to allocate goods and services among consumers, how to allocate gains from production/trade among consumers etc. These questions can be analyzed at micro or macro level.

From perspective of economic theory this distinction is, to a large degree, irrelevant but for applied economics it is important, as microeconomics studies behavior of individuals (like consumers, producers, firms, managers etc.), while macroeconomics studies behavior of aggregate variables (like employment, gross domestic product, inflation etc.). Traditionally economic questions (or more precisely answers) are divided into positive and normative. Positive economics explains how economy works or predicts some future trends, while normative economics is more concerned in social welfare and policy recommendations. Some more modern definitions of economics stress that economics deals with incentives, or as Steven Landsburg puts it: Most of economics can be summarized in four words: people respond to incentives.

The rest is commentary. This means that the fundamental question in economics is the analysis of incentives that govern individual choices but also how to design or manipulate incentives so that responding individuals will behave in a desired way. To a large extend economics is an operational science, i.e. economists try to solve real life/economy problems. This does not mean that economists do not use formor theoretical tools. On the contrary much of economic research is based on abstract models.

This requires a comment. Real life economic problems are typically very complicated and it is difficult to analyze them in their full complexity. For this reason economists create models that are supposed to represent the main / important tradeoffs and problems of interest, but still abstract from other (non critical) elements. Hence, by construction models are not realistic and based on questionable assumptions. For this reason economists say that: All models are unreal but some are useful, stressing applicability of model’s results. This argument has been taken to extreme by Milton Friedman in his ”as if” methodological proposal. Friedman stressed that until model’s results fits the real data we can say that individual or economy behaves “as if” it was generated by the model. In such case we say that model represents reality. This is indeed appropriate in some applications, but still one shall be careful, when going with this hypothesis too far.

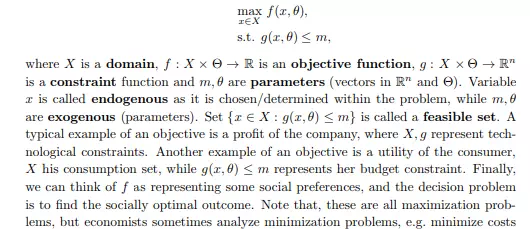

More on methodology of economics can be found in a book by Blaug (1992). There are three typical methods economists use: constrained optimization, equilibrium analysis and comparative statics. We now briefly describe each of them. Example of a constrained optimization problem is:

of producing at least x units of output. All in all, constrained optimization is part of a decision theory and is one of the most typical economic tools. As we mentioned before, economists use constrained optimization problems for various reasons. They (i) solve ’real life’ constrained optimization problems to find the best feasible solution; or (ii) assuming a family of optimization problems (for various θ) is given they estimate parameters θ from the observed data, such that solutions to the optimization problem are similar to the one observed in the real data. Finally, they also (iii) ’invent’ constrained optimization problems, whose solutions coincide with observed choices. In (i) they often create a recommendation for a decision maker, forecast some economic variables or explain incentive and trade-offs that decision maker must be aware of; in

(ii) they provide information about parameters θ that can be used for other economic considerations (comparisons, forecasts), or provide interpretation of identified θ in behavioral terms; finally in (iii) economists must invent X, f, g so that the solutions to constrained optimization problem represent (usually uniquely) an observed real life data. This is linked to revealed preference argument, as decision maker reveals his objective and constraints via actual choices.