The master road builders

In Europe, gradual technological improvements in the 17th and 18th centuries saw increased commercial travel, improved vehicles, and the breeding of better horses. These factors created an incessant demand for better roads, and supply and invention both rose to meet that demand. In 1585 the Italian engineer Guido Toglietta wrote a thoughtful treatise on a pavement system using broken stone that represented a marked advance on the heavy Roman style. In 1607 Thomas Procter published the first English-language book on roads. The first highway engineering school in Europe, the School of Bridges and Highways, was founded in Paris in 1747. Late in the 18th century the Scottish political economist Adam Smith, in discussing conditions in England, wrote,

Good roads, canals, and navigable rivers, by diminishing the expense of carriage, put the remote parts of the country more nearly upon a level with those in the neighbourhood of a town. They are upon that account the greatest of all improvements.

Up to this time roads had been built, with minor modifications, to the heavy Roman cross section, but in the last half of the 18th century the fathers of modern road building and road maintenance appeared in France and Britain.

Trésaguet

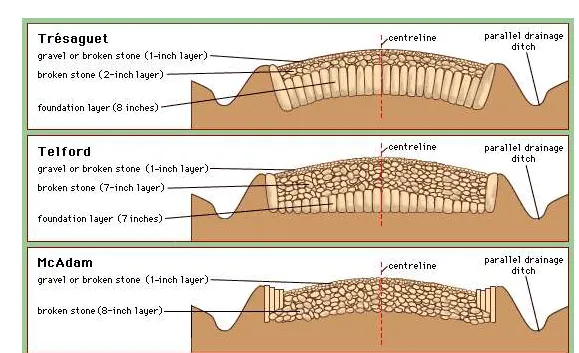

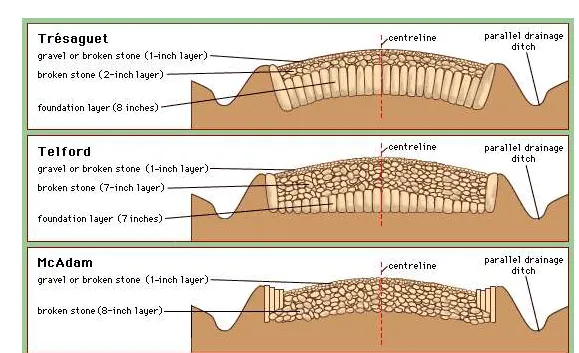

In France, Pierre-Marie-Jérôme Trésaguet, an engineer from an engineering family, became in 1764 engineer of bridges and roads at Limoges and in 1775 inspector general of roads and bridges for France. In that year he developed an entirely new type of relatively light road surface, based on the theory that the underlying natural formation, rather than the pavement, should support the load. His standard cross section (shown in the figure, top) was 18 feet wide and consisted of an eight-inch-thick course of uniform foundation stones laid edgewise on the natural formation and covered by a two-inch layer of walnut-sized broken stone. This second layer was topped with a one-inch layer of smaller gravel or broken stone. In order to maintain surface levels, Trésaguet’s pavement was placed in an excavated trench—a technique that made drainage a difficult problem.

Cross sections of three 18th-century European roads, as designed by (top) Pierre Trésaguet, (middle) Thomas Telford, and (bottom) John McAdam.

Thomas Telford, born of poor parents in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, in 1757, was apprenticed to a stone mason. Intelligent and ambitious, Telford progressed to designing bridges and building roads. He placed great emphasis on two features: (1) maintaining a level roadway with a maximum gradient of 1 in 30 and (2) building a stone surface capable of carrying the heaviest anticipated loads. His roadways were 18 feet wide and built in three courses: (1) a lower layer, seven inches thick, consisting of good-quality foundation stone carefully placed by hand (this was known as the Telford base), (2) a middle layer, also seven inches thick, consisting of broken stone of two-inch maximum size, and (3) a top layer of gravel or broken stone up to one inch thick. (See figure, middle.)

The greatest advance came from John Loudon McAdam, born in 1756 at Ayr in Scotland. McAdam began his road-building career in 1787 but reached major heights after 1804, when he was appointed general surveyor for Bristol, then the most important port city in England. The roads leading to Bristol were in poor condition, and in 1816 McAdam took control of the Bristol Turnpike. There he showed that traffic could be supported by a relatively thin layer of small, single-sized, angular pieces of broken stone placed and compacted on a well-drained natural formation and covered by an impermeable surface of smaller stones. He had no use for the masonry constructions of his predecessors and contemporaries.

Drainage was essential to the success of McAdam’s method, and he required the pavement to be elevated above the surrounding surface. The structural layer of broken stone (as shown in the figure, bottom) was eight inches thick and used stone of two to three inches maximum size laid in layers and compacted by traffic—a process adequate for the traffic of the time. The top layer was two inches thick, using three-fourths- to one-inch stone to fill surface voids between the large stones. Continuing maintenance was essential.

Although McAdam drew on the successes and failures of others, his total structural reliance on broken stone represented the largest paradigm shift in the history of road pavements. The principles of the “macadam” road are still used today. McAdam’s success was also due to his efficient administration and his strong view that road managers needed skill and motivation.