Negligence

Negligence is a careless act that causes harm to another person. As with other torts, the victim is entitled to take legal action to be compensated for that loss or injury. In adjudicating tort cases, the goal is to find the right balance that appropriately compensates victims of negligence yet does not discourage legitimate activity or make the legal standards for businesses too onerous. While the term “professional negligence” is often used, there is no separate tort by that name; it merely refers to negligence committed by a professional person like an accountant or lawyer.

Burden of Proof

To succeed in a negligence action, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant: 1) owed a duty of care; 2) breached the standard of care; and 3) caused harm to the plaintiff. Each of these elements will be discussed in more detail in the following pages.

Step 1: Was a Duty of Care Owed?

According to the neighbour principle, “a defendant owes a duty of care to anyone who might be reasonably affected by the defendant’s conduct.”62 Based on Donoghue v. Stevenson, the Canadian courts have developed a unique test for whether a duty of care is owed. In the first place, the judge will ascertain whether or not the duty of care question has already been answered for the particular type of case being litigated. For example, a duty of care is owed by a beverage bottler to a consumer. If there is no existing precedent, a duty of care will be established only if 1) it is reasonably foreseeable that the plaintiff could be injured by the defendant’s carelessness, 2) there was a relationship of sufficient proximity, and 3) there are no public policy grounds for denying the duty of care.

Reasonable Foreseeability

This is an objective test of whether a reasonable person in the defendant’s position would have recognized the possibility that his activities might injure the plaintiff. The theory is that the plaintiff should not be denied compensation simply because the defendant was not paying attention; on the other hand, it would be impossible for any defendant to foresee all possible dangers.

Proximity or Causation

Put simply, “there must somehow be a close and direct connection between the parties.” Therefore, depending on the facts of the situation, a relationship of proximity may arise from:

· Physical proximity;

· A social relationship (e.g., parent and child);

· A commercial relationship (e.g., store and patron);

· A direct causal connection between the defendant’s carelessness and the plaintiff’s injury; and/or

· The plaintiff’s reliance on the fact that the defendant represented that it would act in a certain way.

In establishing proximity, the law treats careless statements differently from careless actions. This is because the risks associated with statements are often far less apparent than the risk associated with actions. As well, the impact of a careless statement can be almost limitless whereas the risks associated with physical actions are limited in time and space. Finally, careless statements generally result in a pure economic loss, and the courts are more reluctant to provide compensation for pure economic losses compared to property damage or personal injuries.

In Hercules Managements Ltd. v. Ernst & Young (1997), 146 DLR (4th) 577 (S.C.C.), the court established that a duty of care is more likely to be imposed with respect to a professional statement if the defendant:

· Possessed, or claimed to have, special knowledge;

· Made the statement during a serious occasion, such as a business meeting;

· Was responding to an inquiry made by the plaintiff;

· Received a financial benefit for making the statement;

· Communicated a statement of fact or an opinion based on fact (e.g., a professional evaluation) rather than a purely personal opinion; and/or

· Did not issue a disclaimer.

Moreover, to avoid “indeterminate liability,” a duty of care will be recognized only if:

· The defendant knew that the plaintiff, either individually or as a member of a defined group (e.g., shareholders), might rely on the statement; and

· The plaintiff relied on the statement for its intended purpose (e.g., management of the company vs. investment advice).

In summary, whether a duty of care is imposed on a professional depends both on the existence of a close relationship with the defendant and the extent to which the client relied on the professional.

Policy

Lastly, even if there was foreseeability and proximate cause, the court may deny liability on policy grounds for the wider benefit of the legal system and society. For example, the courts may be concerned that acknowledging a duty of care will flood the legal system with similar lawsuits (e.g., if a regulatory body was held liable for the actions of the professionals it governs), interfere with political decisions (e.g., how much money a municipality spends repairing potholes), or hurt a valuable relationship (one reason a mother does not owe a duty of care to her unborn child).

Step 2: Was the Standard of Care Breached?

The standard of care indicates how a defendant should act; it is breached when the defendant acts less carefully.

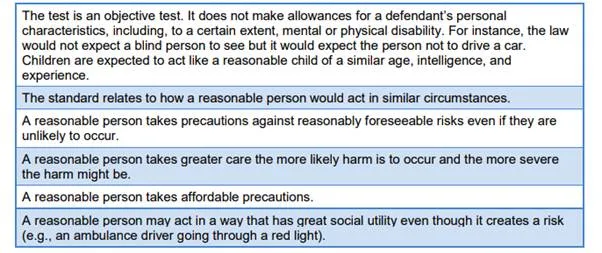

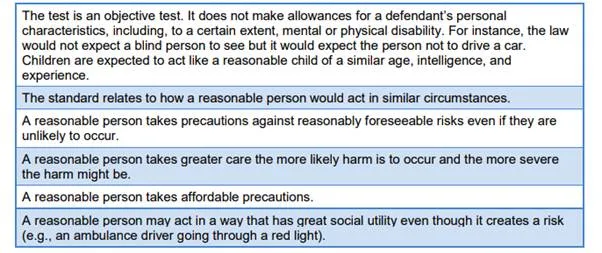

The standard of care is based on the mythical reasonable person, someone of “normal intelligence who makes prudence a guide to his conduct.”67 In other words, it is “someone of average intelligence who will prudently exercise reasonable care, considering all of the circumstances.”68 Some of the relevant factors pertaining to the reasonable person test are shown in Figure

Figure : Reasonable Person Test

Step 3: Did the Breach Cause the Harm?

The third and final element to be proved in a negligence case is that the defendant’s carelessness caused the plaintiff to suffer a loss. The test used is the “but-for test.” The question to be asked is: “‘but for’ the defendant’s actions, would the injury or damage not have occurred?”70 While an affirmative answer to this question would suggest that there is proximate cause, the facts of the situation can often make it difficult to tell whether there is proximity, especially when there are intervening events.

As was discussed under intentional torts, a loss may be held to be too remote. A loss is too remote if it was not reasonably foreseeable that the careless action could cause the loss.

Generally speaking, the closer in time the defendant’s conduct is to the injury suffered by the victim, the more likely it is to be found to be the cause of the injury.

The thin skull theory says that if it was reasonably foreseeable that a normal person would have suffered some damage from the defendant’s negligence, the plaintiff who is unusually vulnerable due to either physical or psychological infirmity is entitled to damages for all his or her losses. However, if a normal person would not have suffered any damages, the plaintiff would not be entitled to damages. Similarly, the thin wallet theory says that a defendant is generally not responsible for the fact that the plaintiff suffered to an unusual extent because he or she was poor.

The remoteness principle is also used to deal with intervening acts, events that occur after the defendant’s carelessness and that cause the plaintiff to suffer an additional injury. In view of an intervening act, the loss may be ruled to be too remote from the defendant’s carelessness and therefore save the defendant from liability.

As is the case with the other elements, the plaintiff has to prove causation on a balance of probabilities. The courts generally apply an all-or-nothing approach, meaning that if there is at least a 51% chance that the defendant’s carelessness caused the plaintiff’s loss, the defendant will be awarded damages for all of that loss. As well, the plaintiff has to prove only that the defendant’s carelessness was one cause, not the only cause.

In the case of multiple defendants, if different defendants cause the plaintiff to suffer different injuries, liability is apportioned accordingly. However, if different defendants cause a single injury, they will be held jointly and severally for the loss, meaning that the plaintiff can recover all of the damages from one defendant or some from each defendant.