Acceptance Of An Offer

Acceptance “occurs when an offeree agrees to enter into the contract proposed by the offeror.”88 The moment an offer is accepted, a contract is formed and each party is bound to comply with its terms.

To be valid, acceptance must be:

1. In a positive form, whether oral or by act;

2. Unequivocal – It must be complete and unconditional;

3. Without any variation in the terms of the offer or, as noted above, it will constitute a counter-offer and terminate the original offer; and

4. Communicated to the offeror – Some contracts may specify that notice of acceptance is not necessary and that the contract will be binding as soon as the offeree has performed whatever was required of him in the offer. Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. established that an offer may be made to an indefinite number of people who remain unknown to the offeree even after they have accepted.

Bilateral Contracts and Unilateral Contracts

How an offer is accepted depends on the type of contract. A bilateral contract occurs when a promise is exchanged for a promise. In that case, acceptance may occur through written or spoken words or by conduct (e.g., shaking hands or nodding agreeably). Silence will be viewed as a manner of acceptance only in very limited circumstances. When there is no face-to-face contact, it may be necessary to determine where and when a contract was formed or, if the lines of communication have broken down, whether a contract was even formed.

The general rule is that acceptance by instantaneous communication (where there is little or no delay in the interaction between the parties) is effective when and where it is received by the offeror. Otherwise, according to the postal rule, acceptance by non-instantaneous communication is effective where and when the offeree sends it.

The format of communication may be detailed in the offer. However, as long as the way in which acceptance is communicated results in the acceptance being received within the same time frame as if it had been done using the method specified in the offer, and as long as industry practice is followed, the court will deem it proper communication. More specifically, acceptance by mail is deemed to be effective when a properly addressed and stamped letter of acceptance is dropped in the mail unless the offer indicates that acceptance should be by means other than post; in that case, acceptance is not effective until the offeror receives the letter.

In a unilateral contract, the offer is accepted by performing one or more acts required by the terms of the offer. For example, the purchaser of a preventive medicine accepts the manufacturer’s offer of a money-back guarantee simply by purchasing the product. There is no expectation of formally communicating an acceptance to the manufacturer. The obligation now rests with the manufacturer to perform its part of the bargain.

Consideration

Consideration is the price for which the promise (or the act) of another is bought.91 It is an exchange of value that must move from each party of the contract but not necessarily to the other party. It is enough to promise a benefit to someone; it is not necessary to provide a benefit to the other party to the contract.

“The main goal of contract law is to enforce bargains. And as business people know, a bargain involves more than an offer and an acceptance. It also involves a mutual exchange of value.”92 Consideration offers a sure legal test for binding commercial relationships. Without consideration, a contract is simply a gratuitous promise that is not enforceable. There must be sufficient consideration, which is anything of value in the eyes of the law. However, consideration does not have to be adequate, meaning that it does not need to have the same value as the consideration given in exchange. The court will not assess the adequacy of the consideration unless there are special circumstances such as suspicions of fraud or undue influence. However, a person who requests goods or services from another is obligated by an implied promise to pay a reasonable price for the goods or services. Rather than seeking damages for breach of contract, the supplier of the goods or services would seek payment under the principle of quantum meruit (reasonable payment for services rendered).

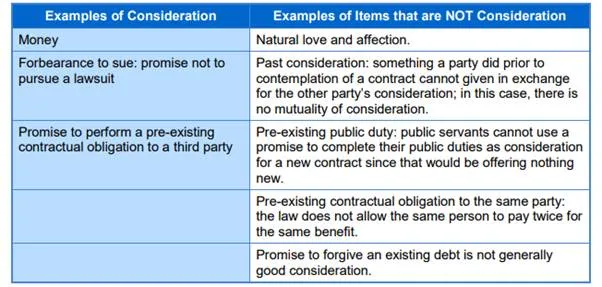

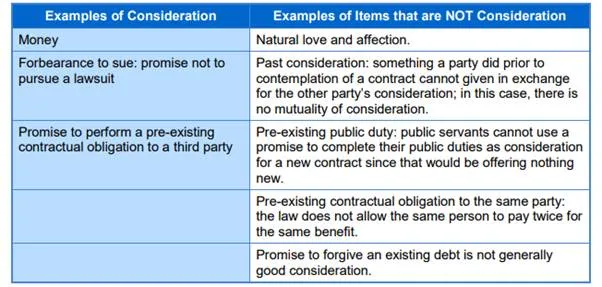

Figure helps to answer the question of what constitutes consideration in the eyes of the law.

Figure: What is consideration?

The rule that forgiving an existing debt is not consideration is often viewed as unjust and unrealistic. After all, a creditor may find it more beneficial to settle for a reduced amount than to insist on full payment if it would mean getting some cash sooner or avoiding pushing the debtor into bankruptcy. Therefore, the courts have ruled that a promise to accept less money is enforceable if the debtor gives something new in exchange, even if that only means paying one day earlier than required or accepting goods/services in exchange for cancelling the debt. Finally, in Ontario, the Mercantile Law Amendment Act binds a creditor who agrees to accept part performance of an obligation in settlement of a debt. Many other Canadian jurisdictions have similar acts.

Exceptions to the Requirement for Consideration

There are two situations where the law will enforce promises not supported by consideration.

Use of a Seal

The law recognizes and enforces agreements made under seal since the seal is accepted in lieu of consideration. A seal is a mark that is put on a written contract to indicate a party’s intention to be bound by the terms of the document even though the other party has not given consideration. An insignia used to be pressed into hot wax, but now a small red adhesive circle is used instead. It is even sufficient to write “seal” on the document as long as this is done at the same time as the party signs the document.

It may be that the click of a mouse will become the newest seal when it is tested in the court by the first party that tries to enforce a promised but undelivered Internet-based benefit.

Equitable Estoppel (Promissory Estoppel)

Under the principle of equitable estoppel, the courts have provided equitable relief when one person asserts certain facts as true or makes gratuitous promises, and another relies on the statement or gratuitous promise to his or her detriment. The maker of the statement or promise will be estopped or prevented from denying the truth of the original statement or claiming that he or she was not bound by the promise despite the fact that consideration has not flowed.

In Canada, equitable estoppel is limited to a defence against a claim by the promisor where the statement is made in the context of an existing legal relationship. It applies when 1) a promise or statement was made by one party—by words or conduct—that was intended to affect their relationship and be acted on; 2) the defendant relied on the statement in a way that makes it unfair for the other party to retract its promise; and 3) the defendant’s own conduct was beyond reproach.

Recent cases have raised the question of whether Canadian courts are moving towards the American principle of injurious reliance as a cause of action, which allows an injured party to force the promisor to perform the promise. In 2008, for example, the Ontario Superior Court upheld an employee’s claim for a promised wage increase on a number of grounds including promissory estoppe.