Cancer and the Cell Cycle

Cancer is a collective name for many different diseases caused by a common mechanism: uncontrolled cell division. Despite the redundancy and overlapping levels of cell-cycle control, errors occur. One of the critical processes monitored by the cell-cycle checkpoint surveillance mechanism is the proper replication of DNA during the S phase. Even when all of the cell-cycle controls are fully functional, a small percentage of replication errors (mutations) will be passed on to the daughter cells. If one of these changes to the DNA nucleotide sequence occurs within a gene, a gene mutation results. All cancers begin when a gene mutation gives rise to a faulty protein that participates in the process of cell reproduction. The change in the cell that results from the malformed protein may be minor. Even minor mistakes, however, may allow subsequent mistakes to occur more readily. Over and over, small, uncorrected errors are passed from parent cell to daughter cells and accumulate as each generation of cells produces more non-functional proteins from uncorrected DNA damage. Eventually, the pace of the cell cycle speeds up as the effectiveness of the control and repair mechanisms decreases. Uncontrolled growth of the mutated cells outpaces the growth of normal cells in the area, and a tumor can result.

Proto-oncogenes

The genes that code for the positive cell-cycle regulators are called proto-oncogenes. Proto-oncogenes are normal genes that, when mutated, become oncogenes—genes that cause a cell to become cancerous. Consider what might happen to the cell cycle in a cell with a recently acquired oncogene. In most instances, the alteration of the DNA sequence will result in a less functional (or non-functional) protein. The result is detrimental to the cell and will likely prevent the cell from completing the cell cycle; however, the organism is not harmed because the mutation will not be carried forward. If a cell cannot reproduce, the mutation is not propagated and the damage is minimal. Occasionally, however, a gene mutation causes a change that increases the activity of a positive regulator. For example, a mutation that allows Cdk, a protein involved in cell-cycle regulation, to be activated before it should be could push the cell cycle past a checkpoint before all of the required conditions are met. If the resulting daughter cells are too damaged to undertake further cell divisions, the mutation would not be propagated and no harm comes to the organism. However, if the atypical daughter cells are able to divide further, the subsequent generation of cells will likely accumulate even more mutations, some possibly in additional genes that regulate the cell cycle.

The Cdk example is only one of many genes that are considered proto-oncogenes. In addition to the cell-cycle regulatory proteins, any protein that influences the cycle can be altered in such a way as to override cell-cycle checkpoints. Once a proto-oncogene has been altered such that there is an increase in the rate of the cell cycle, it is then called an oncogene.

Tumor Suppressor Genes

Like proto-oncogenes, many of the negative cell-cycle regulatory proteins were discovered in cells that had become cancerous. Tumor suppressor genes are genes that code for the negative regulator proteins, the type of regulator that—when activated—can prevent the cell from undergoing uncontrolled division. The collective function of the best-understood tumor suppressor gene proteins, retinoblastoma protein (RB1), p53, and p21, is to put up a roadblock to cell-cycle progress until certain events are completed. A cell that carries a mutated form of a negative regulator might not be able to halt the cell cycle if there is a problem.

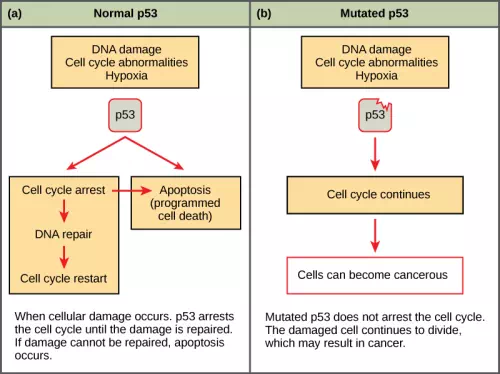

Mutated p53 genes have been identified in more than half of all human tumor cells. This discovery is not surprising in light of the multiple roles that the p53 protein plays at the G1 checkpoint. The p53 protein activates other genes whose products halt the cell cycle (allowing time for DNA repair), activates genes whose products participate in DNA repair, or activates genes that initiate cell death when DNA damage cannot be repaired. A damaged p53 gene can result in the cell behaving as if there are no mutations (Figure 6.8). This allows cells to divide, propagating the mutation in daughter cells and allowing the accumulation of new mutations. In addition, the damaged version of p53 found in cancer cells cannot trigger cell death.

Figure 6.8 (a) The role of p53 is to monitor DNA. If damage is detected, p53 triggers repair mechanisms. If repairs are unsuccessful, p53 signals apoptosis. (b) A cell with an abnormal p53 protein cannot repair damaged DNA and cannot signal apoptosis. Cells with abnormal p53 can become cancerous. (credit: modification of work by Thierry Soussi)

Cancer is the result of unchecked cell division caused by a breakdown of the mechanisms regulating the cell cycle. The loss of control begins with a change in the DNA sequence of a gene that codes for one of the regulatory molecules. Faulty instructions lead to a protein that does not function as it should. Any disruption of the monitoring system can allow other mistakes to be passed on to the daughter cells. Each successive cell division will give rise to daughter cells with even more accumulated damage. Eventually, all checkpoints become nonfunctional, and rapidly reproducing cells crowd out normal cells, resulting in tumorous growth.