Electrochemical Gradient

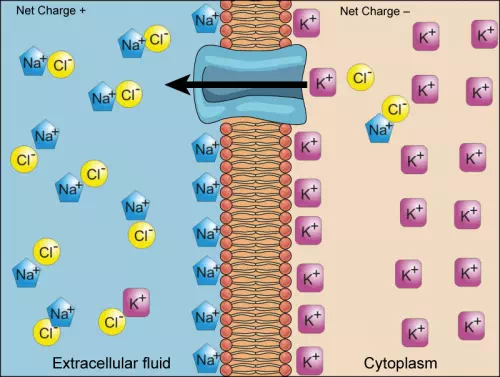

We have discussed simple concentration gradients—differential concentrations of a substance across a space or a membrane—but in living systems, gradients are more complex. Because cells contain proteins, most of which are negatively charged, and because ions move into and out of cells, there is an electrical gradient, a difference of charge, across the plasma membrane. The interior of living cells is electrically negative with respect to the extracellular fluid in which they are bathed; at the same time, cells have higher concentrations of potassium (K+) and lower concentrations of sodium (Na+) than does the extracellular fluid. Thus, in a living cell, the concentration gradient and electrical gradient of Na+ promotes diffusion of the ion into the cell, and the electrical gradient of Na+ (a positive ion) tends to drive it inward to the negatively charged interior. The situation is more complex, however, for other elements such as potassium. The electrical gradient of K+ promotes diffusion of the ion into the cell, but the concentration gradient of K+ promotes diffusion out of the cell (Figure 3.28). The combined gradient that affects an ion is called its electrochemical gradient, and it is especially important to muscle and nerve cells.

Figure 3.28 Electrochemical gradients arise from the combined effects of concentration gradients and electrical gradients. (credit: modification of work by “Synaptitude”/Wikimedia Commons)

Moving Against a Gradient

To move substances against a concentration or an electrochemical gradient, the cell must use energy. This energy is harvested from ATP that is generated through cellular metabolism. Active transport mechanisms, collectively called pumps or carrier proteins, work against electrochemical gradients. With the exception of ions, small substances constantly pass through plasma membranes. Active transport maintains concentrations of ions and other substances needed by living cells in the face of these passive changes. Much of a cell’s supply of metabolic energy may be spent maintaining these processes. Because active transport mechanisms depend on cellular metabolism for energy, they are sensitive to many metabolic poisons that interfere with the supply of ATP.

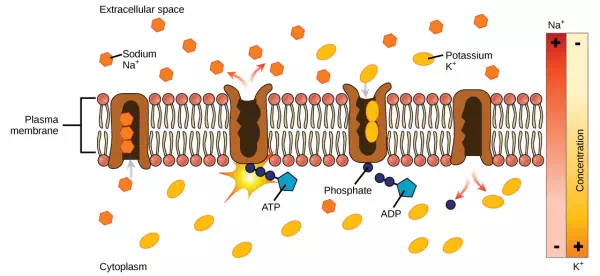

Two mechanisms exist for the transport of small-molecular weight material and macromolecules. Primary active transport moves ions across a membrane and creates a difference in charge across that membrane. The primary active transport system uses ATP to move a substance, such as an ion, into the cell, and often at the same time, a second substance is moved out of the cell. The sodium-potassium pump, an important pump in animal cells, expends energy to move potassium ions into the cell and a different number of sodium ions out of the cell (Figure 3.29). The action of this pump results in a concentration and charge difference across the membrane.

Figure 3.29 The sodium-potassium pump move potassium and sodium ions across the plasma membrane. (credit: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal)

Secondary active transport describes the movement of material using the energy of the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport. Using the energy of the electrochemical gradient created by the primary active transport system, other substances such as amino acids and glucose can be brought into the cell through membrane channels. ATP itself is formed through secondary active transport using a hydrogen ion gradient in the mitochondrion.