Animal Cells versus Plant Cells

Despite their fundamental similarities, there are some striking differences between animal and plant cells (see Table 3.1). Animal cells have centrioles, centrosomes (discussed under the cytoskeleton), and lysosomes, whereas plant cells do not. Plant cells have a cell wall, chloroplasts, plasmodesmata, and plastids used for storage, and a large central vacuole, whereas animal cells do not.

The Cell Wall

In Figure 3.8 b, the diagram of a plant cell, you see a structure external to the plasma membrane called the cell wall. The cell wall is a rigid covering that protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell. Fungal and protist cells also have cell walls.

While the chief component of prokaryotic cell walls is peptidoglycan, the major organic molecule in the plant cell wall is cellulose, a polysaccharide made up of long, straight chains of glucose units. When nutritional information refers to dietary fiber, it is referring to the cellulose content of food.

Chloroplasts

Like mitochondria, chloroplasts also have their own DNA and ribosomes. Chloroplasts function in photosynthesis and can be found in eukaryotic cells such as plants and algae. In photosynthesis, carbon dioxide, water, and light energy are used to make glucose and oxygen. This is the major difference between plants and animals: Plants (autotrophs) are able to make their own food, like glucose, whereas animals (heterotrophs) must rely on other organisms for their organic compounds or food source.

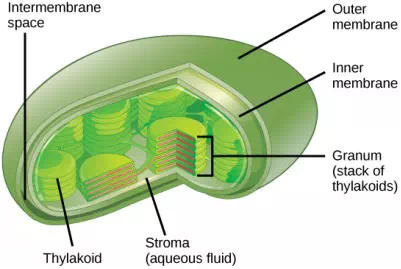

Like mitochondria, chloroplasts have outer and inner membranes, but within the space enclosed by a chloroplastís inner membrane is a set of interconnected and stacked, fluid-filled membrane sacs called thylakoids (Figure 3.18). Each stack of thylakoids is called a granum (plural = grana). The fluid enclosed by the inner membrane and surrounding the grana is called the stroma.

†

†

†

Figure 3.18 This simplified diagram of a chloroplast shows the outer membrane, inner membrane, thylakoids, grana, and stroma.

The chloroplasts contain a green pigment called chlorophyll, which captures the energy of sunlight for photosynthesis. Like plant cells, photosynthetic protists also have chloroplasts. Some bacteria also perform photosynthesis, but they do not have chloroplasts. Their photosynthetic pigments are located in the thylakoid membrane within the cell itself.

Endosymbiosis

We have mentioned that both mitochondria and chloroplasts contain DNA and ribosomes. Have you wondered why? Strong evidence points to endosymbiosis as the explanation.

Symbiosis is a relationship in which organisms from two separate species live in close association and typically exhibit specific adaptations to each other. Endosymbiosis (endo-= within) is a relationship in which one organism lives inside the other. Endosymbiotic relationships abound in nature. Microbes that produce vitamin K live inside the human gut. This relationship is beneficial for us because we are unable to synthesize vitamin K. It is also beneficial for the microbes because they are protected from other organisms and are provided a stable habitat and abundant food by living within the large intestine.

Scientists have long noticed that bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts are similar in size. We also know that mitochondria and chloroplasts have DNA and ribosomes, just as bacteria do and they resemble the types found in bacteria. Scientists believe that host cells and bacteria formed a mutually beneficial endosymbiotic relationship when the host cells ingested aerobic bacteria and cyanobacteria but did not destroy them. Through evolution, these ingested bacteria became more specialized in their functions, with the aerobic bacteria becoming mitochondria and the photosynthetic bacteria becoming chloroplasts.

The Central Vacuole

Previously, we mentioned vacuoles as essential components of plant cells. If you look at Figure 3.8 b, you will see that plant cells each have a large, central vacuole that occupies most of the cell. The central vacuole plays a key role in regulating the cellís concentration of water in changing environmental conditions. In plant cells, the liquid inside the central vacuole provides turgor pressure, which is the outward pressure caused by the fluid inside the cell. Have you ever noticed that if you forget to water a plant for a few days, it wilts? That is because as the water concentration in the soil becomes lower than the water concentration in the plant, water moves out of the central vacuoles and cytoplasm and into the soil. As the central vacuole shrinks, it leaves the cell wall unsupported. This loss of support to the cell walls of a plant results in the wilted appearance. Additionally, this fluid has a very bitter taste, which discourages consumption by insects and animals. The central vacuole also functions to store proteins in developing seed cells.

Extracellular Matrix of Animal Cells

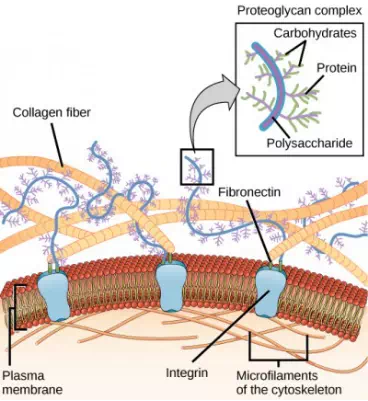

Most animal cells release materials into the extracellular space. The primary components of these materials are glycoproteins and the protein collagen. Collectively, these materials are called the extracellular matrix (Figure 3.19). Not only does the extracellular matrix hold the cells together to form a tissue, but it also allows the cells within the tissue to communicate with each other.

†

†

†

Figure 3.19 The extracellular matrix consists of a network of substances secreted by cells.

Blood clotting provides an example of the role of the extracellular matrix in cell communication. When the cells lining a blood vessel are damaged, they display a protein receptor called tissue factor. When tissue factor binds with another factor in the extracellular matrix, it causes platelets to adhere to the wall of the damaged blood vessel, stimulates adjacent smooth muscle cells in the blood vessel to contract (thus constricting the blood vessel), and initiates a series of steps that stimulate the platelets to produce clotting factors.

Intercellular Junctions

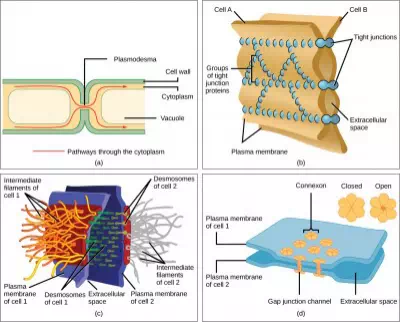

Cells can also communicate with each other by direct contact, referred to as intercellular junctions. There are some differences in the ways that plant and animal cells do this. Plasmodesmata (singular = plasmodesma) are junctions between plant cells, whereas animal cell contacts include tight and gap junctions, and desmosomes.

In general, long stretches of the plasma membranes of neighboring plant cells cannot touch one another because they are separated by the cell walls surrounding each cell. Plasmodesmata are numerous channels that pass between the cell walls of adjacent plant cells, connecting their cytoplasm and enabling signal molecules and nutrients to be transported from cell to cell (Figure 3.20 a).

†

†

†

Figure 3.20 There are four kinds of connections between cells. (a) A plasmodesma is a channel between the cell walls of two adjacent plant cells. (b) Tight junctions join adjacent animal cells. (c) Desmosomes join two animal cells together. (d) Gap junctions act as channels between animal cells. (credit b, c, d: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

A tight junction is a watertight seal between two adjacent animal cells (Figure 3.20 b). Proteins hold the cells tightly against each other. This tight adhesion prevents materials from leaking between the cells. Tight junctions are typically found in the epithelial tissue that lines internal organs and cavities, and composes most of the skin. For example, the tight junctions of the epithelial cells lining the urinary bladder prevent urine from leaking into the extracellular space.

Also found only in animal cells are desmosomes, which act like spot welds between adjacent epithelial cells (Figure 3.20 c). They keep cells together in a sheet-like formation in organs and tissues that stretch, like the skin, heart, and muscles.

Gap junctions in animal cells are like plasmodesmata in plant cells in that they are channels between adjacent cells that allow for the transport of ions, nutrients, and other substances that enable cells to communicate (Figure 3.20 d). Structurally, however, gap junctions and plasmodesmata differ.

Table 3.1 This table provides the components of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells and their respective functions.

|

Components of Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells and Their Functions |

||||

|

Cell Component |

Function |

Present in Prokaryotes? |

Present in Animal Cells? |

Present in Plant Cells? |

|

Plasma membrane |

Separates cell from external environment; controls passage of organic molecules, ions, water, oxygen, and wastes into and out of the cell |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Cytoplasm |

Provides structure to cell; site of many metabolic reactions; medium in which organelles are found |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Nucleoid |

Location of DNA |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Nucleus |

Cell organelle that houses DNA and directs synthesis of ribosomes and proteins |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Ribosomes |

Protein synthesis |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mitochondria |

ATP production/cellular respiration |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Peroxisomes |

Oxidizes and breaks down fatty acids and amino acids, and detoxifies poisons |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Vesicles and vacuoles |

Storage and transport; digestive function in plant cells |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Centrosome |

Unspecified role in cell division in animal cells; organizing center of microtubules in animal cells |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Lysosomes |

Digestion of macromolecules; recycling of worn-out organelles |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Cell wall |

Protection, structural support and maintenance of cell shape |

Yes, primarily peptidoglycan in bacteria but not Archaea |

No |

Yes, primarily cellulose |

|

Chloroplasts |

Photosynthesis |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Endoplasmic reticulum |

Modifies proteins and synthesizes lipids |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Golgi apparatus |

Modifies, sorts, tags, packages, and distributes lipids and proteins |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Cytoskeleton |

Maintains cellís shape, secures organelles in specific positions, allows cytoplasm and vesicles to move within the cell, and enables unicellular organisms to move independently |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Flagella |

Cellular locomotion |

Some |

Some |

No, except for some plant sperm. |

|

Cilia |

Cellular locomotion, movement of particles along extracellular surface of plasma membrane, and filtration |

No |

Some |

No |

Summary

Like a prokaryotic cell, a eukaryotic cell has a plasma membrane, cytoplasm, and ribosomes, but a eukaryotic cell is typically larger than a prokaryotic cell, has a true nucleus (meaning its DNA is surrounded by a membrane), and has other membrane-bound organelles that allow for compartmentalization of functions. The plasma membrane is a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins. The nucleolus within the nucleus is the site for ribosome assembly. Ribosomes are found in the cytoplasm or are attached to the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane or endoplasmic reticulum. They perform protein synthesis. Mitochondria perform cellular respiration and produce ATP. Peroxisomes break down fatty acids, amino acids, and some toxins. Vesicles and vacuoles are storage and transport compartments. In plant cells, vacuoles also help break down macromolecules.

Animal cells also have a centrosome and lysosomes. The centrosome has two bodies, the centrioles, with an unknown role in cell division. Lysosomes are the digestive organelles of animal cells.

Plant cells have a cell wall, chloroplasts, and a central vacuole. The plant cell wall, whose primary component is cellulose, protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell. Photosynthesis takes place in chloroplasts. The central vacuole expands, enlarging the cell without the need to produce more cytoplasm.

The endomembrane system includes the nuclear envelope, the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, vesicles, as well as the plasma membrane. These cellular components work together to modify, package, tag, and transport membrane lipids and proteins.

The cytoskeleton has three different types of protein elements. Microfilaments provide rigidity and shape to the cell, and facilitate cellular movements. Intermediate filaments bear tension and anchor the nucleus and other organelles in place. Microtubules help the cell resist compression, serve as tracks for motor proteins that move vesicles through the cell, and pull replicated chromosomes to opposite ends of a dividing cell. They are also the structural elements of centrioles, flagella, and cilia.

Animal cells communicate through their extracellular matrices and are connected to each other by tight junctions, desmosomes, and gap junctions. Plant cells are connected and communicate with each other by plasmodesmata.