Mucosal Surfaces and Immune Tolerance

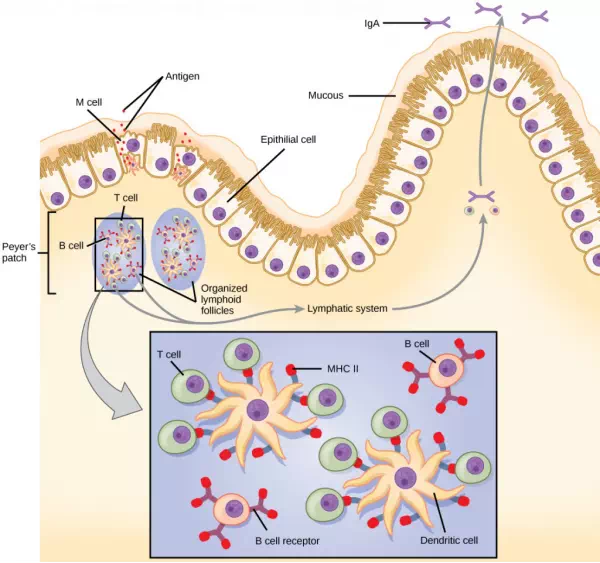

The innate and adaptive immune responses discussed thus far comprise the systemic immune system (affecting the whole body), which is distinct from the mucosal immune system. Mucosal immunity is formed by mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, which functions independently of the systemic immune system, and which has its own innate and adaptive components. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), illustrated in Figure 23.15, is a collection of lymphatic tissue that combines with epithelial tissue lining the mucosa throughout the body. This tissue functions as the immune barrier and response in areas of the body with direct contact to the external environment. The systemic and mucosal immune systems use many of the same cell types. Foreign particles that make their way to MALT are taken up by absorptive epithelial cells called M cells and delivered to APCs located directly below the mucosal tissue. M cells function in the transport described, and are located in the Peyer’s patch, a lymphoid nodule. APCs of the mucosal immune system are primarily dendritic cells, with B cells and macrophages having minor roles. Processed antigens displayed on APCs are detected by T cells in the MALT and at various mucosal induction sites, such as the tonsils, adenoids, appendix, or the mesenteric lymph nodes of the intestine. Activated T cells then migrate through the lymphatic system and into the circulatory system to mucosal sites of infection.

Figure 23.15. The topology and function of intestinal MALT is shown. Pathogens are taken up by M cells in the intestinal epithelium and excreted into a pocket formed by the inner surface of the cell. The pocket contains antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells, which engulf the antigens, then present them with MHC II molecules on the cell surface. The dendritic cells migrate to an underlying tissue called a Peyer’s patch. Antigen-presenting cells, T cells, and B cells aggregate within the Peyer’s patch, forming organized lymphoid follicles. There, some T cells and B cells are activated. Other antigen-loaded dendritic cells migrate through the lymphatic system where they activate B cells, T cells, and plasma cells in the lymph nodes. The activated cells then return to MALT tissue effector sites. IgA and other antibodies are secreted into the intestinal lumen.

MALT is a crucial component of a functional immune system because mucosal surfaces, such as the nasal passages, are the first tissues onto which inhaled or ingested pathogens are deposited. The mucosal tissue includes the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus, and the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and urogenital tracts.

The immune system has to be regulated to prevent wasteful, unnecessary responses to harmless substances, and more importantly so that it does not attack “self.” The acquired ability to prevent an unnecessary or harmful immune response to a detected foreign substance known not to cause disease is described as immune tolerance. Immune tolerance is crucial for maintaining mucosal homeostasis given the tremendous number of foreign substances (such as food proteins) that APCs of the oral cavity, pharynx, and gastrointestinal mucosa encounter. Immune tolerance is brought about by specialized APCs in the liver, lymph nodes, small intestine, and lung that present harmless antigens to an exceptionally diverse population of regulatory T (Treg) cells, specialized lymphocytes that suppress local inflammation and inhibit the secretion of stimulatory immune factors. The combined result of Treg cells is to prevent immunologic activation and inflammation in undesired tissue compartments and to allow the immune system to focus on pathogens instead. In addition to promoting immune tolerance of harmless antigens, other subsets of Treg cells are involved in the prevention of the autoimmune response, which is an inappropriate immune response to host cells or self-antigens. Another Treg class suppresses immune responses to harmful pathogens after the infection has cleared to minimize host cell damage induced by inflammation and cell lysis.

Immunological Memory

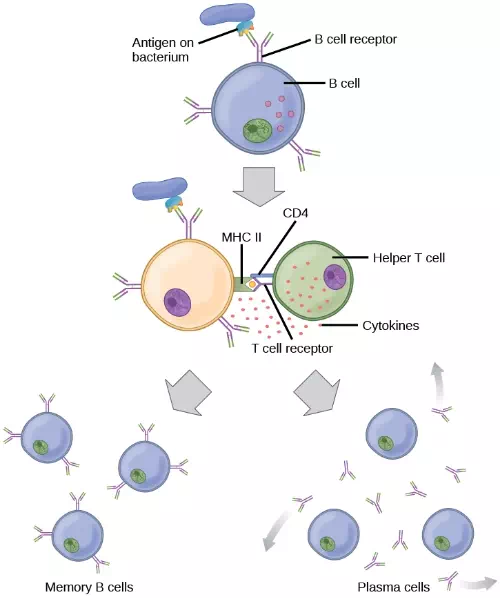

The adaptive immune system possesses a memory component that allows for an efficient and dramatic response upon reinvasion of the same pathogen. Memory is handled by the adaptive immune system with little reliance on cues from the innate response. During the adaptive immune response to a pathogen that has not been encountered before, called a primary response, plasma cells secreting antibodies and differentiated T cells increase, then plateau over time. As B and T cells mature into effector cells, a subset of the naïve populations differentiates into B and T memory cells with the same antigen specificities, as illustrated in Figure 23.16.

A memory cell is an antigen-specific B or T lymphocyte that does not differentiate into effector cells during the primary immune response, but that can immediately become effector cells upon re-exposure to the same pathogen. During the primary immune response, memory cells do not respond to antigens and do not contribute to host defenses. As the infection is cleared and pathogenic stimuli subside, the effectors are no longer needed, and they undergo apoptosis. In contrast, the memory cells persist in the circulation.

Figure 23.16. After initially binding an antigen to the B cell receptor (BCR), a B cell internalizes the antigen and presents it on MHC II. A helper T cell recognizes the MHC II–antigen complex and activates the B cell. As a result, memory B cells and plasma cells are made.

The Rh antigen is found on Rh-positive red blood cells. An Rh-negative female can usually carry an Rh-positive fetus to term without difficulty. However, if she has a second Rh-positive fetus, her body may launch an immune attack that causes hemolytic disease of the newborn. Why do you think hemolytic disease is only a problem during the second or subsequent pregnancies?

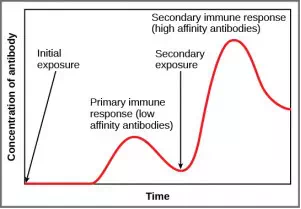

If the pathogen is never encountered again during the individual’s lifetime, B and T memory cells will circulate for a few years or even several decades and will gradually die off, having never functioned as effector cells. However, if the host is re-exposed to the same pathogen type, circulating memory cells will immediately differentiate into plasma cells and CTLs without input from APCs or TH cells. One reason the adaptive immune response is delayed is because it takes time for naïve B and T cells with the appropriate antigen specificities to be identified and activated. Upon reinfection, this step is skipped, and the result is a more rapid production of immune defenses. Memory B cells that differentiate into plasma cells output tens to hundreds-fold greater antibody amounts than were secreted during the primary response, as the graph in Figure 23.17illustrates. This rapid and dramatic antibody response may stop the infection before it can even become established, and the individual may not realize they had been exposed.

Figure 23.17. In the primary response to infection, antibodies are secreted first from plasma cells. Upon re-exposure to the same pathogen, memory cells differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells that output a greater amount of antibody for a longer period of time.

Vaccination is based on the knowledge that exposure to noninfectious antigens, derived from known pathogens, generates a mild primary immune response. The immune response to vaccination may not be perceived by the host as illness but still confers immune memory. When exposed to the corresponding pathogen to which an individual was vaccinated, the reaction is similar to a secondary exposure. Because each reinfection generates more memory cells and increased resistance to the pathogen, and because some memory cells die, certain vaccine courses involve one or more booster vaccinations to mimic repeat exposures: for instance, tetanus boosters are necessary every ten years because the memory cells only live that long.

Mucosal Immune Memory

A subset of T and B cells of the mucosal immune system differentiates into memory cells just as in the systemic immune system. Upon reinvasion of the same pathogen type, a pronounced immune response occurs at the mucosal site where the original pathogen deposited, but a collective defense is also organized within interconnected or adjacent mucosal tissue. For instance, the immune memory of an infection in the oral cavity would also elicit a response in the pharynx if the oral cavity was exposed to the same pathogen.

Vaccinologist

Vaccination (or immunization) involves the delivery, usually by injection as shown in Figure 23.18, of noninfectious antigen(s) derived from known pathogens. Other components, called adjuvants, are delivered in parallel to help stimulate the immune response. Immunological memory is the reason vaccines work. Ideally, the effect of vaccination is to elicit immunological memory, and thus resistance to specific pathogens without the individual having to experience an infection.

Figure 23.18. Vaccines are often delivered by injection into the arm. (credit: U.S. Navy Photographer’s Mate Airman Apprentice Christopher D. Blachly)

Vaccinologists are involved in the process of vaccine development from the initial idea to the availability of the completed vaccine. This process can take decades, can cost millions of dollars, and can involve many obstacles along the way. For instance, injected vaccines stimulate the systemic immune system, eliciting humoral and cell-mediated immunity, but have little effect on the mucosal response, which presents a challenge because many pathogens are deposited and replicate in mucosal compartments, and the injection does not provide the most efficient immune memory for these disease agents. For this reason, vaccinologists are actively involved in developing new vaccines that are applied via intranasal, aerosol, oral, or transcutaneous (absorbed through the skin) delivery methods. Importantly, mucosal-administered vaccines elicit both mucosal and systemic immunity and produce the same level of disease resistance as injected vaccines.

Figure 23.19. The polio vaccine can be administered orally. (credit: modification of work by UNICEF Sverige)

Currently, a version of intranasal influenza vaccine is available, and the polio and typhoid vaccines can be administered orally, as shown in Figure 23.19. Similarly, the measles and rubella vaccines are being adapted to aerosol delivery using inhalation devices. Eventually, transgenic plants may be engineered to produce vaccine antigens that can be eaten to confer disease resistance. Other vaccines may be adapted to rectal or vaginal application to elicit immune responses in rectal, genitourinary, or reproductive mucosa. Finally, vaccine antigens may be adapted to transdermal application in which the skin is lightly scraped and microneedles are used to pierce the outermost layer. In addition to mobilizing the mucosal immune response, this new generation of vaccines may end the anxiety associated with injections and, in turn, improve patient participation.