Adaptive Immune Response

The adaptive, or acquired, immune response takes days or even weeks to become established—much longer than the innate response; however, adaptive immunity is more specific to pathogens and has memory. Adaptive immunity is an immunity that occurs after exposure to an antigen either from a pathogen or a vaccination. This part of the immune system is activated when the innate immune response is insufficient to control an infection. In fact, without information from the innate immune system, the adaptive response could not be mobilized. There are two types of adaptive responses: the cell-mediated immune response, which is carried out by T cells, and the humoral immune response, which is controlled by activated B cells and antibodies. Activated T cells and B cells that are specific to molecular structures on the pathogen proliferate and attack the invading pathogen. Their attack can kill pathogens directly or secrete antibodies that enhance the phagocytosis of pathogens and disrupt the infection. Adaptive immunity also involves a memory to provide the host with long-term protection from reinfection with the same type of pathogen; on re-exposure, this memory will facilitate an efficient and quick response.

Antigen-presenting Cells

Unlike NK cells of the innate immune system, B cells (B lymphocytes) are a type of white blood cell that gives rise to antibodies, whereas T cells (T lymphocytes) are a type of white blood cell that plays an important role in the immune response. T cells are a key component in the cell-mediated response—the specific immune response that utilizes T cells to neutralize cells that have been infected with viruses and certain bacteria. There are three types of T cells: cytotoxic, helper, and suppressor T cells. Cytotoxic T cells destroy virus-infected cells in the cell-mediated immune response, and helper T cells play a part in activating both the antibody and the cell-mediated immune responses. Suppressor T cells deactivate T cells and B cells when needed, and thus prevent the immune response from becoming too intense.

An antigen is a foreign or “non-self” macromolecule that reacts with cells of the immune system. Not all antigens will provoke a response. For instance, individuals produce innumerable “self” antigens and are constantly exposed to harmless foreign antigens, such as food proteins, pollen, or dust components. The suppression of immune responses to harmless macromolecules is highly regulated and typically prevents processes that could be damaging to the host, known as tolerance.

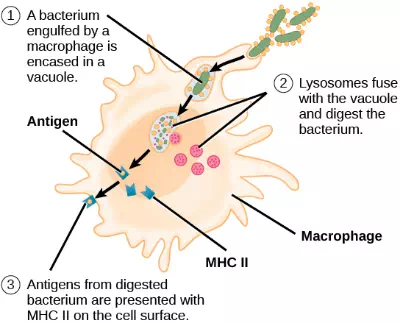

The innate immune system contains cells that detect potentially harmful antigens, and then inform the adaptive immune response about the presence of these antigens. An antigen-presenting cell (APC) is an immune cell that detects, engulfs, and informs the adaptive immune response about an infection. When a pathogen is detected, these APCs will phagocytose the pathogen and digest it to form many different fragments of the antigen. Antigen fragments will then be transported to the surface of the APC, where they will serve as an indicator to other immune cells. Dendritic cells are immune cells that process antigen material; they are present in the skin (Langerhans cells) and the lining of the nose, lungs, stomach, and intestines. Sometimes a dendritic cell presents on the surface of other cells to induce an immune response, thus functioning as an antigen-presenting cell. Macrophages also function as APCs. Before activation and differentiation, B cells can also function as APCs.

After phagocytosis by APCs, the phagocytic vesicle fuses with an intracellular lysosome forming phagolysosome. Within the phagolysosome, the components are broken down into fragments; the fragments are then loaded onto MHC class I or MHC class II molecules and are transported to the cell surface for antigen presentation, as illustrated in Figure 23.8. Note that T lymphocytes cannot properly respond to the antigen unless it is processed and embedded in an MHC II molecule. APCs express MHC on their surfaces, and when combined with a foreign antigen, these complexes signal a “non-self” invader. Once the fragment of antigen is embedded in the MHC II molecule, the immune cell can respond. Helper T- cells are one of the main lymphocytes that respond to antigen-presenting cells. Recall that all other nucleated cells of the body expressed MHC I molecules, which signal “healthy” or “normal.”

Figure 23.8. An APC, such as a macrophage, engulfs and digests a foreign bacterium. An antigen from the bacterium is presented on the cell surface in conjunction with an MHC II molecule Lymphocytes of the adaptive immune response interact with antigen-embedded MHC II molecules to mature into functional immune cells.

T and B Lymphocytes

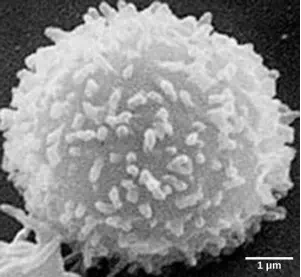

Lymphocytes in human circulating blood are approximately 80 to 90 percent T cells, shown in Figure 23.9, and 10 to 20 percent B cells. Recall that the T cells are involved in the cell-mediated immune response, whereas B cells are part of the humoral immune response.

T cells encompass a heterogeneous population of cells with extremely diverse functions. Some T cells respond to APCs of the innate immune system, and indirectly induce immune responses by releasing cytokines. Other T cells stimulate B cells to prepare their own response. Another population of T cells detects APC signals and directly kills the infected cells. Other T cells are involved in suppressing inappropriate immune reactions to harmless or “self” antigens.

Figure 23.9. This scanning electron micrograph shows a T lymphocyte, which is responsible for the cell-mediated immune response. T cells are able to recognize antigens. (credit: modification of work by NCI; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

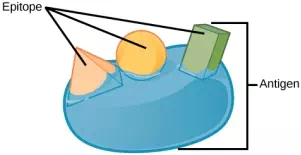

T and B cells exhibit a common theme of recognition/binding of specific antigens via a complementary receptor, followed by activation and self-amplification/maturation to specifically bind to the particular antigen of the infecting pathogen. T and B lymphocytes are also similar in that each cell only expresses one type of antigen receptor. Any individual may possess a population of T and B cells that together express a near limitless variety of antigen receptors that are capable of recognizing virtually any infecting pathogen. T and B cells are activated when they recognize small components of antigens, called epitopes, presented by APCs, illustrated in Figure 23.10. Note that recognition occurs at a specific epitope rather than on the entire antigen; for this reason, epitopes are known as “antigenic determinants.” In the absence of information from APCs, T and B cells remain inactive, or naïve, and are unable to prepare an immune response. The requirement for information from the APCs of innate immunity to trigger B cell or T cell activation illustrates the essential nature of the innate immune response to the functioning of the entire immune system.

Figure 23.10. An antigen is a macromolecule that reacts with components of the immune system. A given antigen may contain several motifs that are recognized by immune cells. Each motif is an epitope. In this figure, the entire structure is an antigen, and the orange, salmon and green components projecting from it represent potential epitopes.

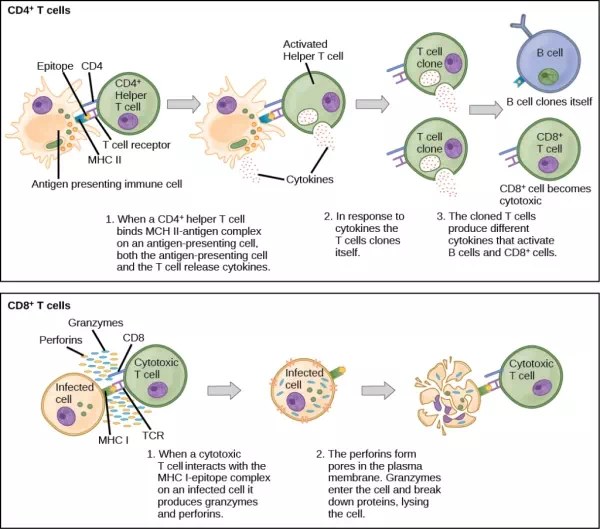

Naïve T cells can express one of two different molecules, CD4 or CD8, on their surface, as shown in Figure 23.11, and are accordingly classified as CD4+ or CD8+ cells. These molecules are important because they regulate how a T cell will interact with and respond to an APC. Naïve CD4+ cells bind APCs via their antigen-embedded MHC II molecules and are stimulated to become helper T (TH) lymphocytes, cells that go on to stimulate B cells (or cytotoxic T cells) directly or secrete cytokines to inform more and various target cells about the pathogenic threat. In contrast, CD8+ cells engage antigen-embedded MHC I molecules on APCs and are stimulated to become cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), which directly kill infected cells by apoptosis and emit cytokines to amplify the immune response. The two populations of T cells have different mechanisms of immune protection, but both bind MHC molecules via their antigen receptors called T cell receptors (TCRs). The CD4 or CD8 surface molecules differentiate whether the TCR will engage an MHC II or an MHC I molecule. Because they assist in binding specificity, the CD4 and CD8 molecules are described as coreceptors.

Figure 23.11. Naïve CD4+ T cells engage MHC II molecules on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and become activated. Clones of the activated helper T cell, in turn, activate B cells and CD8+ T cells, which become cytotoxic T cells. Cytotoxic T cells kill infected cells.

Which of the following statements about T cells is false?

1. Helper T cells release cytokines while cytotoxic T cells kill the infected cell.

2. Helper T cells are CD4+, while cytotoxic T cells are CD8+.

3. MHC II is a receptor found on most body cells, while MHC I is a receptor found on immune cells only.

4. The T cell receptor is found on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

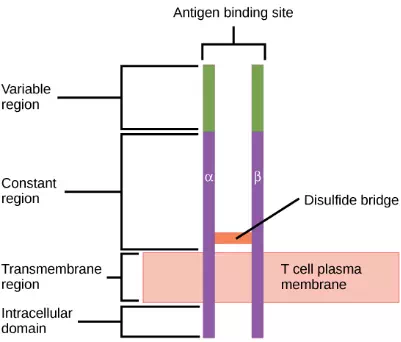

Consider the innumerable possible antigens that an individual will be exposed to during a lifetime. The mammalian adaptive immune system is adept in responding appropriately to each antigen. Mammals have an enormous diversity of T cell populations, resulting from the diversity of TCRs. Each TCR consists of two polypeptide chains that span the T cell membrane, as illustrated in Figure 23.12; the chains are linked by a disulfide bridge. Each polypeptide chain is comprised of a constant domain and a variable domain: a domain, in this sense, is a specific region of a protein that may be regulatory or structural. The intracellular domain is involved in intracellular signaling. A single T cell will express thousands of identical copies of one specific TCR variant on its cell surface. The specificity of the adaptive immune system occurs because it synthesizes millions of different T cell populations, each expressing a TCR that differs in its variable domain. This TCR diversity is achieved by the mutation and recombination of genes that encode these receptors in stem cell precursors of T cells. The binding between an antigen-displaying MHC molecule and a complementary TCR “match” indicates that the adaptive immune system needs to activate and produce that specific T cell because its structure is appropriate to recognize and destroy the invading pathogen.

Figure 23.12. A T cell receptor spans the membrane and projects variable binding regions into the extracellular space to bind processed antigens via MHC molecules on APCs.

Helper T Lymphocytes

The TH lymphocytes function indirectly to identify potential pathogens for other cells of the immune system. These cells are important for extracellular infections, such as those caused by certain bacteria, helminths, and protozoa. TH lymphocytes recognize specific antigens displayed in the MHC II complexes of APCs. There are two major populations of TH cells: TH1 and TH2. TH1 cells secrete cytokines to enhance the activities of macrophages and other T cells. TH1 cells activate the action of cyotoxic T cells, as well as macrophages. TH2 cells stimulate naïve B cells to destroy foreign invaders via antibody secretion. Whether a TH1 or a TH2 immune response develops depends on the specific types of cytokines secreted by cells of the innate immune system, which in turn depends on the nature of the invading pathogen.

The TH1-mediated response involves macrophages and is associated with inflammation. Recall the frontline defenses of macrophages involved in the innate immune response. Some intracellular bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, have evolved to multiply in macrophages after they have been engulfed. These pathogens evade attempts by macrophages to destroy and digest the pathogen. When M. tuberculosis infection occurs, macrophages can stimulate naïve T cells to become TH1 cells. These stimulated T cells secrete specific cytokines that send feedback to the macrophage to stimulate its digestive capabilities and allow it to destroy the colonizing M. tuberculosis. In the same manner, TH1-activated macrophages also become better suited to ingest and kill tumor cells. In summary; TH1 responses are directed toward intracellular invaders while TH2 responses are aimed at those that are extracellular.

B Lymphocytes

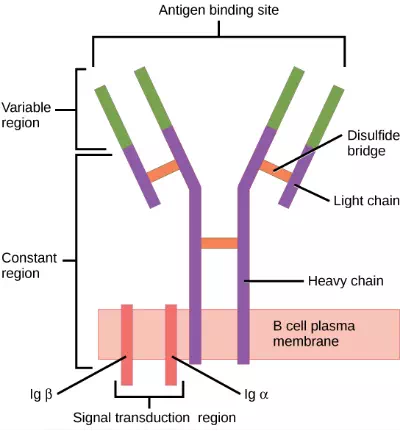

When stimulated by the TH2 pathway, naïve B cells differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells. A plasma cell is an immune cell that secrets antibodies; these cells arise from B cells that were stimulated by antigens. Similar to T cells, naïve B cells initially are coated in thousands of B cell receptors (BCRs), which are membrane-bound forms of Ig (immunoglobulin, or an antibody). The B cell receptor has two heavy chains and two light chains connected by disulfide linkages. Each chain has a constant and a variable region; the latter is involved in antigen binding. Two other membrane proteins, Ig alpha and Ig beta, are involved in signaling. The receptors of any particular B cell, as shown in Figure 23.13 are all the same, but the hundreds of millions of different B cells in an individual have distinct recognition domains that contribute to extensive diversity in the types of molecular structures to which they can bind. In this state, B cells function as APCs. They bind and engulf foreign antigens via their BCRs and then display processed antigens in the context of MHC II molecules to TH2 cells. When a TH2 cell detects that a B cell is bound to a relevant antigen, it secretes specific cytokines that induce the B cell to proliferate rapidly, which makes thousands of identical (clonal) copies of it, and then it synthesizes and secretes antibodies with the same antigen recognition pattern as the BCRs. The activation of B cells corresponding to one specific BCR variant and the dramatic proliferation of that variant is known as clonal selection. This phenomenon drastically, but briefly, changes the proportions of BCR variants expressed by the immune system, and shifts the balance toward BCRs specific to the infecting pathogen.

Figure 23.13. B cell receptors are embedded in the membranes of B cells and bind a variety of antigens through their variable regions. The signal transduction region transfers the signal into the cell.

T and B cells differ in one fundamental way: whereas T cells bind antigens that have been digested and embedded in MHC molecules by APCs, B cells function as APCs that bind intact antigens that have not been processed. Although T and B cells both react with molecules that are termed “antigens,” these lymphocytes actually respond to very different types of molecules. B cells must be able to bind intact antigens because they secrete antibodies that must recognize the pathogen directly, rather than digested remnants of the pathogen. Bacterial carbohydrate and lipid molecules can activate B cells independently from the T cells.

Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes

CTLs, a subclass of T cells, function to clear infections directly. The cell-mediated part of the adaptive immune system consists of CTLs that attack and destroy infected cells. CTLs are particularly important in protecting against viral infections; this is because viruses replicate within cells where they are shielded from extracellular contact with circulating antibodies. When APCs phagocytize pathogens and present MHC I-embedded antigens to naïve CD8+ T cells that express complementary TCRs, the CD8+ T cells become activated to proliferate according to clonal selection. These resulting CTLs then identify non-APCs displaying the same MHC I-embedded antigens (for example, viral proteins)—for example, the CTLs identify infected host cells.

Intracellularly, infected cells typically die after the infecting pathogen replicates to a sufficient concentration and lyses the cell, as many viruses do. CTLs attempt to identify and destroy infected cells before the pathogen can replicate and escape, thereby halting the progression of intracellular infections. CTLs also support NK lymphocytes to destroy early cancers. Cytokines secreted by the TH1 response that stimulates macrophages also stimulate CTLs and enhance their ability to identify and destroy infected cells and tumors.

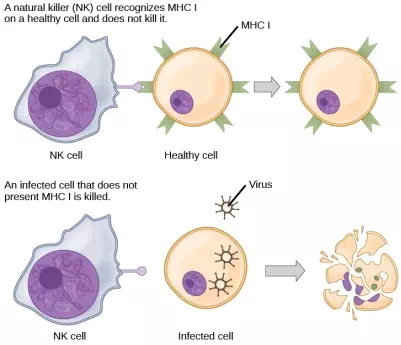

CTLs sense MHC I-embedded antigens by directly interacting with infected cells via their TCRs. Binding of TCRs with antigens activates CTLs to release perforin and granzyme, degradative enzymes that will induce apoptosis of the infected cell. Recall that this is a similar destruction mechanism to that used by NK cells. In this process, the CTL does not become infected and is not harmed by the secretion of perforin and granzymes. In fact, the functions of NK cells and CTLs are complementary and maximize the removal of infected cells, as illustrated in Figure 23.14. If the NK cell cannot identify the “missing self” pattern of down-regulated MHC I molecules, then the CTL can identify it by the complex of MHC I with foreign antigens, which signals “altered self.” Similarly, if the CTL cannot detect antigen-embedded MHC I because the receptors are depleted from the cell surface, NK cells will destroy the cell instead. CTLs also emit cytokines, such as interferons, that alter surface protein expression in other infected cells, such that the infected cells can be easily identified and destroyed. Moreover, these interferons can also prevent virally infected cells from releasing virus particles.

Figure 23.14. Natural killer (NK) cells recognize the MHC I receptor on healthy cells. If MHC I is absent, the cell is lysed.

Based on what you know about MHC receptors, why do you think an organ transplanted from an incompatible donor to a recipient will be rejected?

Plasma cells and CTLs are collectively called effector cells: they represent differentiated versions of their naïve counterparts, and they are involved in bringing about the immune defense of killing pathogens and infected host cells.