Pheromones

A pheromone is a chemical released by an animal that affects the behavior or physiology of animals of the same species. Pheromonal signals can have profound effects on animals that inhale them, but pheromones apparently are not consciously perceived in the same way as other odors. There are several different types of pheromones, which are released in urine or as glandular secretions. Certain pheromones are attractants to potential mates, others are repellants to potential competitors of the same sex, and still others play roles in mother-infant attachment. Some pheromones can also influence the timing of puberty, modify reproductive cycles, and even prevent embryonic implantation. While the roles of pheromones in many nonhuman species are important, pheromones have become less important in human behavior over evolutionary time compared to their importance to organisms with more limited behavioral repertoires.

The vomeronasal organ (VNO, or Jacobson’s organ) is a tubular, fluid-filled, olfactory organ present in many vertebrate animals that sits adjacent to the nasal cavity. It is very sensitive to pheromones and is connected to the nasal cavity by a duct. When molecules dissolve in the mucosa of the nasal cavity, they then enter the VNO where the pheromone molecules among them bind with specialized pheromone receptors. Upon exposure to pheromones from their own species or others, many animals, including cats, may display the flehmen response (shown in Figure 17.9), a curling of the upper lip that helps pheromone molecules enter the VNO.

Pheromonal signals are sent, not to the main olfactory bulb, but to a different neural structure that projects directly to the amygdala (recall that the amygdala is a brain center important in emotional reactions, such as fear). The pheromonal signal then continues to areas of the hypothalamus that are key to reproductive physiology and behavior. While some scientists assert that the VNO is apparently functionally vestigial in humans, even though there is a similar structure located near human nasal cavities, others are researching it as a possible functional system that may, for example, contribute to synchronization of menstrual cycles in women living in close proximity.

Figure 17.9. The flehmen response in this tiger results in the curling of the upper lip and helps airborne pheromone molecules enter the vomeronasal organ. (credit: modification of work by “chadh”/Flickr)

Taste

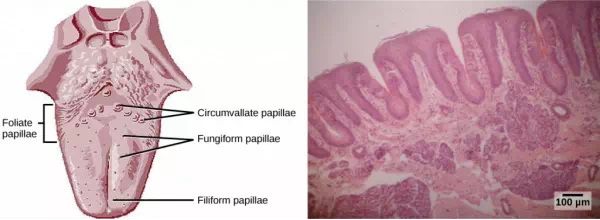

Detecting a taste (gustation) is fairly similar to detecting an odor (olfaction), given that both taste and smell rely on chemical receptors being stimulated by certain molecules. The primary organ of taste is the taste bud. A taste bud is a cluster of gustatory receptors (taste cells) that are located within the bumps on the tongue called papillae (singular: papilla) (illustrated in Figure 17.10). There are several structurally distinct papillae. Filiform papillae, which are located across the tongue, are tactile, providing friction that helps the tongue move substances, and contain no taste cells. In contrast, fungiform papillae, which are located mainly on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, each contain one to eight taste buds and also have receptors for pressure and temperature. The large circumvallate papillae contain up to 100 taste buds and form a V near the posterior margin of the tongue.

Figure 17.10. (a) Foliate, circumvallate, and fungiform papillae are located on different regions of the tongue. (b) Foliate papillae are prominent protrusions on this light micrograph. (credit a: modification of work by NCI; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

In addition to those two types of chemically and mechanically sensitive papillae are foliate papillae—leaf-like papillae located in parallel folds along the edges and toward the back of the tongue, as seen in the Figure 17.10 micrograph. Foliate papillae contain about 1,300 taste buds within their folds. Finally, there are circumvallate papillae, which are wall-like papillae in the shape of an inverted “V” at the back of the tongue. Each of these papillae is surrounded by a groove and contains about 250 taste buds.

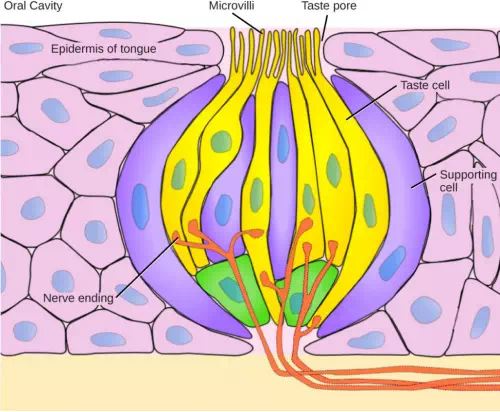

Each taste bud’s taste cells are replaced every 10 to 14 days. These are elongated cells with hair-like processes called microvilli at the tips that extend into the taste bud pore (illustrate in Figure 17.11). Food molecules (tastants) are dissolved in saliva, and they bind with and stimulate the receptors on the microvilli. The receptors for tastants are located across the outer portion and front of the tongue, outside of the middle area where the filiform papillae are most prominent.

Figure 17.11. Pores in the tongue allow tastants to enter taste pores in the tongue. (credit: modification of work by Vincenzo Rizzo)

In humans, there are five primary tastes, and each taste has only one corresponding type of receptor. Thus, like olfaction, each receptor is specific to its stimulus (tastant). Transduction of the five tastes happens through different mechanisms that reflect the molecular composition of the tastant. A salty tastant (containing NaCl) provides the sodium ions (Na+) that enter the taste neurons and excite them directly. Sour tastants are acids and belong to the thermoreceptor protein family. Binding of an acid or other sour-tasting molecule triggers a change in the ion channel and these increase hydrogen ion (H+) concentrations in the taste neurons, thus depolarizing them. Sweet, bitter, and umami tastants require a G-protein coupled receptor. These tastants bind to their respective receptors, thereby exciting the specialized neurons associated with them.

Both tasting abilities and sense of smell change with age. In humans, the senses decline dramatically by age 50 and continue to decline. A child may find a food to be too spicy, whereas an elderly person may find the same food to be bland and unappetizing.

Smell and Taste in the Brain

Olfactory neurons project from the olfactory epithelium to the olfactory bulb as thin, unmyelinated axons. The olfactory bulb is composed of neural clusters called glomeruli, and each glomerulus receives signals from one type of olfactory receptor, so each glomerulus is specific to one odorant. From glomeruli, olfactory signals travel directly to the olfactory cortex and then to the frontal cortex and the thalamus. Recall that this is a different path from most other sensory information, which is sent directly to the thalamus before ending up in the cortex. Olfactory signals also travel directly to the amygdala, thereafter reaching the hypothalamus, thalamus, and frontal cortex. The last structure that olfactory signals directly travel to is a cortical center in the temporal lobe structure important in spatial, autobiographical, declarative, and episodic memories. Olfaction is finally processed by areas of the brain that deal with memory, emotions, reproduction, and thought.

Taste neurons project from taste cells in the tongue, esophagus, and palate to the medulla, in the brainstem. From the medulla, taste signals travel to the thalamus and then to the primary gustatory cortex. Information from different regions of the tongue is segregated in the medulla, thalamus, and cortex.

Summary

There are five primary tastes in humans: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami. Each taste has its own receptor type that responds only to that taste. Tastants enter the body and are dissolved in saliva. Taste cells are located within taste buds, which are found on three of the four types of papillae in the mouth.

Regarding olfaction, there are many thousands of odorants, but humans detect only about 10,000. Like taste receptors, olfactory receptors are each responsive to only one odorant. Odorants dissolve in nasal mucosa, where they excite their corresponding olfactory sensory cells. When these cells detect an odorant, they send their signals to the main olfactory bulb and then to other locations in the brain, including the olfactory cortex.