7 Problems of Urban Transport

While urban transport has had a tremendous liberating impact, it has also posed a very serious problem to the urban impact in which it operates. Buchanan gave a warning in 1963 when he wrote Traffic in Towns, that “the motor vehicle has been responsible for much that adversely effects our physical surrounding.

There is its direct competition for space with environmental requirements, and it is greatest where space is limited… the record is one of steady encroachment, often in small instalments, but cumulative in effect. There are the visual consequences of this intrusion; the crowding out of every available square yard of space with vehicles, either moving or stationary, so that buildings seem to rise from a plinth of cars; the destruction of architectural scenes; visual effects from the cutter of signs, signals, bollards, railings, etc., associated with the use of motor vehicles”.

1. Traffic Movement and Congestion:

Traffic congestion occurs when urban transport networks are no longer capable of accommodating the volume of movements that use them. The location of congested areas is determined by the physical transport framework and by the patterns of urban land use and their associated trip-generating activities. Levels of traffic overloading vary in time, with a very well-marked peak during the daily journey-to-work periods.

Although most congestion can be attributed to overloading, there are other aspects of this basic problem that also require solutions. In the industrialised countries increasing volumes of private car, public transport and commercial vehicle traffic have exposed the inadequacies of urban roads, especially in older city centres where street patterns have survived largely unaltered from the nineteenth century and earlier.

The intricate nature of these centres makes motorised movements difficult and long-term car parking almost impossible. In developing countries the problem is particularly acute: Indian and South-East Asian cities often have cores composed of a mesh of narrow streets often accessible only to non-motorised traffic.

The rapid growth in private car ownership and use in western cities in the period since 1950 has rarely been accompanied by a corresponding upgrading of the road network, and these increases will probably continue into the twenty-first century, further exacerbating the problem. In less-developed countries car ownership in urban areas is in at a much lower level but there is evidence of an increased rate in recent decades, especially in South America and South-East Asia (Rimmer, 1977).

Satisfactory definitions of the saturation level of car ownership vary but if a ratio of 50 cars to 100 persons is taken then in several US cities the figure is now over 80 per 100, whereas in South-East Asian cities the level rarely exceeds 10 per 100. One factor contributing to congestion in developing world cities is the uncontrolled intermixing of motorised and animal-or human-drawn vehicles. The proliferation of pedal and motorcycles causes particular difficulties (Simon 1996).

2. Public Transport Crowding:

The ‘person congestion’ occurring inside public transport vehicles at such peak times adds insult to injury, sometimes literally. A very high proportion of the day’s journeys are made under conditions of peak-hour loading, during which there will be lengthy queues at stops, crowding at terminals, stairways and ticket offices, and excessively long periods of hot and claustrophobic travel jammed in overcrowded vehicles.

In Japan, ‘packers’ are employed on station platforms to ensure that passengers are forced inside the metro trains so that the automatic doors can close properly. Throughout the world, conditions are difficult on good days, intolerable on bad ones and in some cities in developing countries almost unbelievable every day. Images of passengers hanging on to the outside of trains in India are familiar enough. Quite what conditions are like inside can only be guessed at?

3. Off-Peak Inadequacy of Public Transport:

If public transport operators provide sufficient vehicles to meet peak-hour demand there will be insufficient patronage off-peak to keep them economically employed. If on the other hand they tailor fleet size to the off-peak demand, the vehicles would be so overwhelmed during the peak that the service would most likely break down.

This disparity of vehicle use is the hub of the urban transport problem for public transport operators. Many now have to maintain sufficient vehicles, plant and labour merely to provide a peak-hour service, which is a hopelessly uneconomic use of resources. Often the only way of cutting costs is by reducing off-peak services, but this in turn drives away remaining patronage and encourages further car use. This ‘off-peak problem’ does not, however, afflict operators in developing countries. There, rapidly growing urban populations with low car ownership levels provide sufficient off-peak demand to keep vehicle occupancy rates high throughout the day.

4. Difficulties for Pedestrians:

Pedestrians form the largest category of traffic accident victims. Attempts to increase their safety have usually failed to deal with the source of the problem (i.e., traffic speed and volume) and instead have concentrated on restricting movement on foot. Needless to say this worsens the pedestrian’s environment, making large areas ‘off-limits’ and forcing walkers to use footbridges and underpasses, which are inadequately cleaned or policed. Additionally there is obstruction by parked cars and the increasing pollution of the urban environment, with traffic noise and exhaust fumes affecting most directly those on feet.

At a larger scale, there is the problem of access to facilities and activities in the city. The replacement of small-scale and localised facilities such as shops and clinics by large-scale superstores and hospitals serving larger catchment areas has put many urban activities beyond the reach of the pedestrian. These greater distances between residences and needed facilities can only be covered by those with motorised transport. Whereas the lack of safe facilities may be the biggest problem for the walker in developing countries, in advanced countries it is the growing inability to reach ‘anything’ on foot, irrespective of the quality of the walking environment.

5. Parking Difficulties:

Many car drivers stuck in city traffic jams are not actually trying to go anywhere: they are just looking for a place to park. For them the parking problem is the urban transport problem: earning enough to buy a car is one thing but being smart enough to find somewhere to park it is quite another. However, it is not just the motorist that suffers. Cities are disfigured by ugly multi-storey parking garages and cityscapes are turned into seas of metal, as vehicles are crammed on to every square metre of ground.

Public transport is slowed by clogged streets and movement on foot in anything like a straight line becomes impossible. The provision of adequate car parking space within or on the margins of central business districts (CBDs) for city workers and shoppers is a problem that has serious implications for land use planning.

A proliferation of costly and visually intrusive multi-storey car-parks can only provide a partial solution and supplementary on-street parking often compound road congestion. The extension of pedestrian precincts and retail malls in city centres is intended to provide more acceptable environments for shoppers and other users of city centres. However, such traffic-free zones in turn produce problems as they create new patterns of access to commercial centres for car-borne travellers and users of public transport, while the latter often lose their former advantage of being conveyed directly to the central shopping area.

6. Environmental Impact:

The operation of motor vehicles is a polluting activity. While there are innumerable other activities which cause environmental pollution as a result of the tremendous increases in vehicle ownership, society is only now beginning to appreciate the devastating and dangerous consequences of motor vehicle usage. Pollution is not the only issue.

Traffic noise is a serious problem in the central area of our towns and cities and there are other environmental drawbacks brought about through trying to accommodate increasing traffic volumes. The vast divergence between private and social costs is one, which has so far been allowed to continue without any real check. Perhaps more disturbing is that society is largely unaware of the longer-term effects of such action, and while the motorcar is by no means the only culprit, it is a persistently obvious offender.

Traffic Noise:

It is generally recognised that traffic noise is the major environment problem caused by traffic in urban areas. Noise became a pressing problem late in the 1950s and in 1960 the Government set up a committee to look into the whole issue. This committee, headed by Sir Alan Wilson, pointed out with reference to London that traffic noise “is the predominant source of annoyance and no other single noise is of comparable importance”.

Traffic noise is both annoying and disturbing. Walking and other activities in urban areas can be harassing and, perhaps more important, traffic noise penetrates through to the interior of buildings. Working is therefore more difficult since noise disturbs concentration and conversation. High noise levels can also disturb domestic life as sleeping and relaxation become affected.

Traffic noise tends to be a continuous sound, which is unwanted by the hearer. It is caused as a result of fluctuations in air pressure, which are then picked up by the human ear. Whilst other noise phenomena such as aircraft noise and vibrations from a road drill produce a more intense sound, traffic noise is a much more continuous and an almost round-the-clock discomfort. Noise is usually measured on a weighted scale in decibel units, an increase of 10 dB corresponding to a doubling of loudness.

The Wilson Committee published studies, which showed that a decibel noise level of 84 dB was much as people found acceptable and they proposed legislation which would make any engine noise more than 85 dB, illegal. They proposed that there should be a progressive reduction in acceptable limits, but this has not been achieved. In fact, heavy lorries produce a noise level still well in excess of the above acceptable level.

The noise from motor vehicles comes from various sources. The engine, exhaust and tyres are the most important ones but with goods vehicles, additional noise can be given off by the body, brakes, loose fittings and aerodynamic noise. The level of noise is also influenced by the speed of the vehicle, the density of the traffic flow and the nature of the road surface on which the vehicle is operating.

Vehicles, which are accelerating or travelling on an uphill surface, produce more noise than those moving in a regular flow on an even road. The regulations now in force lay down the limits of 84 dB for cars and 89 dB for Lorries. Buses, particularly when stopping and starting, motorcycles and sports cars as well as goods vehicles produce higher noise levels than the average private car.

7. Atmospheric Pollution:

Fumes from motor vehicles present one of the most unpleasant costs of living with the motor vehicle. The car is just one of many sources of atmospheric pollution and although prolonged exposure may constitute a health hazard, it is important to view this particular problem in perspective. As the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution has stated, “there is no firm evidence that in Britain the present level of these pollutants is a hazard to health”.

Traffic fumes, especially from poorly maintained diesel engines, can be very offensive and added to noise contribute to the unpleasantness of walking in urban areas. No urban street is free from the effects of engine fumes and these almost certainly contribute towards the formation of smog. As traffic volumes increase, however, atmospheric pollution will also increase. In the United States, with its much higher levels of vehicle ownership, there is mounting concern over the effects of vehicle fumes. In large cities such as Mexico City, Los Angeles, New York and Tokyo, fumes are responsible for the creation of very unpleasant smog.

Ecologists believe that the rapid increase in the number of vehicles on our roads which has taken place without (as yet) any real restriction is fast developing into an environmental crisis. Exhaust fumes are the major source of atmospheric pollution by the motor vehicle.

The fumes, which are emitted, contain four main types of pollutant:

(i) Carbon monoxide:

This is a poisonous gas caused as a result of incomplete combustion;

(ii) Unburnt hydrocarbons:

This caused by the evaporation of petrol and the discharge of only partially burnt hydrocarbons;

(iii) Other gases and deposits:

Nitrogen oxides, tetra-ethyl lead and carbon dust particles;

(iv) Aldehydes:

Organic compounds containing the group CHO in their structures.

Hydrocarbon fumes are also emitted from the carburettor and petrol tanks, as well as from the exhaust system.

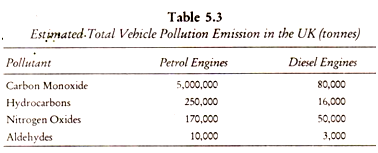

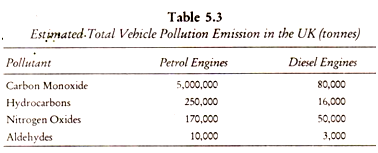

The Royal Commission provides some interesting statistics on the extent of air pollution. In 1970 an estimated 6 million tonnes of carbon monoxide were emitted into the atmosphere. If estimates of vehicle ownership are correct, then by the year 2010, this volume would increase to 14 million tonnes. This figure, however, assumes the current state of engine and fuel technology. A further and more detailed estimate of emissions is given by Sharp in Table 5.3.

Fears of urban pollution by motor vehicles, are greater in the United States and Japan. In day-time Manhattan, for example, readings of pollutants of 25-30 parts per million have been recorded – exposure has the same effect as smoking two packets of cigarettes per day. USA has imposed certain restrictions on vehicle manufacturers and more stringent levels are proposed, but as in the earlier case of traffic noise, increasing vehicle ownership levels are liable to offset some of the benefits which accrue.