Ohm’s Law

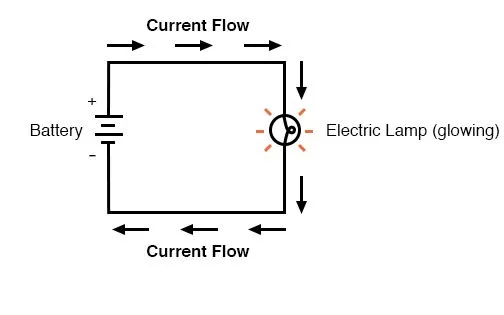

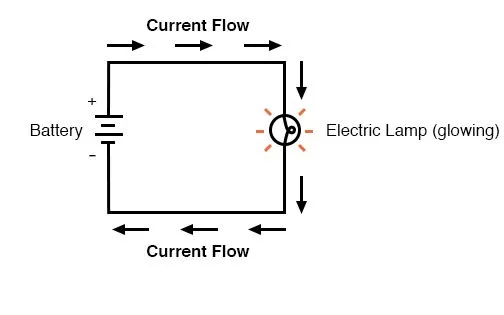

An electric circuit is formed when a conductive path is created to allow electric charge to continuously move. This continuous movement of electric charge through the conductors of a circuit is called a current, and it is often referred to in terms of “flow,” just like the flow of a liquid through a hollow pipe.

The force motivating charge carriers to “flow” in a circuit is called voltage. Voltage is a specific measure of potential energy that is always relative between two points. When we speak of a certain amount of voltage being present in a circuit, we are referring to the measurement of how much potential energy exists to move charge carriers from one particular point in that circuit to another particular point. Without reference to two particular points, the term “voltage” has no meaning.

Current tends to move through the conductors with some degree of friction, or opposition to motion. This opposition to motion is more properly called resistance. The amount of current in a circuit depends on the amount of voltage and the amount of resistance in the circuit to oppose current flow. Just like voltage, resistance is a quantity relative between two points. For this reason, the quantities of voltage and resistance are often stated as being “between” or “across” two points in a circuit.

To be able to make meaningful statements about these quantities in circuits, we need to be able to describe their quantities in the same way that we might quantify mass, temperature, volume, length, or any other kind of physical quantity. For mass we might use the units of “kilogram” or “gram.” For temperature, we might use degrees Fahrenheit or degrees Celsius. Here are the standard units of measurement for electrical current, voltage, and resistance:

The “symbol” given for each quantity is the standard alphabetical letter used to represent that quantity in an algebraic equation. Standardized letters like these are common in the disciplines of physics and engineering and are internationally recognized. The “unit abbreviation” for each quantity represents the alphabetical symbol used as a shorthand notation for its particular unit of measurement. And, yes, that strange-looking “horseshoe” symbol is the capital Greek letter Ω, just a character in a foreign alphabet (apologies to any Greek readers here).

Each unit of measurement is named after a famous experimenter in electricity: The amp after the Frenchman Andre M. Ampere, the volt after the Italian Alessandro Volta, and the ohm after the German Georg Simon Ohm.

The mathematical symbol for each quantity is meaningful as well. The “R” for resistance and the “V” for voltage are both self-explanatory, whereas “I” for current seems a bit weird. The “I” is thought to have been meant to represent “Intensity” (of charge flow), and the other symbol for voltage, “E,” stands for “Electromotive force.” From what research I’ve been able to do, there seems to be some dispute over the meaning of “I.” The symbols “E” and “V” are interchangeable for the most part, although some texts reserve “E” to represent voltage across a source (such as a battery or generator) and “V” to represent voltage across anything else.

All of these symbols are expressed using capital letters, except in cases where a quantity (especially voltage or current) is described in terms of a brief period of time (called an “instantaneous” value). For example, the voltage of a battery, which is stable over a long period of time, will be symbolized with a capital letter “E,” while the voltage peak of a lightning strike at the very instant it hits a power line would most likely be symbolized with a lower-case letter “e” (or lower-case “v”) to designate that value as being at a single moment in time. This same lower-case convention holds true for current as well, the lower-case letter “i” representing current at some instant in time. Most direct-current (DC) measurements, however, being stable over time, will be symbolized with capital letters.

One foundational unit of electrical measurement often taught in the beginnings of electronics courses but used infrequently afterward, is the unit of the coulomb, which is a measure of electric charge proportional to the number of electrons in an imbalanced state. One coulomb of charge is equal to 6,250,000,000,000,000,000 electrons. The symbol for electric charge quantity is the capital letter “Q,” with the unit of coulombs abbreviated by the capital letter “C.” It so happens that the unit for current flow, the amp, is equal to 1 coulomb of charge passing by a given point in a circuit in 1 second of time. Cast in these terms, current is the rate of electric charge motion through a conductor.

As stated before, voltage is the measure of potential energy per unit charge available to motivate current flow from one point to another. Before we can precisely define what a “volt” is, we must understand how to measure this quantity we call “potential energy.” The general metric unit for energy of any kind is the joule, equal to the amount of work performed by a force of 1 newton exerted through a motion of 1 meter (in the same direction). In British units, this is slightly less than 3/4 pound of force exerted over a distance of 1 foot. Put in common terms, it takes about 1 joule of energy to lift a 3/4 pound weight 1 foot off the ground, or to drag something a distance of 1 foot using a parallel pulling force of 3/4 pound. Defined in these scientific terms, 1 volt is equal to 1 joule of electric potential energy per (divided by) 1 coulomb of charge. Thus, a 9-volt battery releases 9 joules of energy for every coulomb of charge moved through a circuit.

These units and symbols for electrical quantities will become very important to know as we begin to explore the relationships between them in circuits.

Ohm’s principal discovery was that the amount of electric current through a metal conductor in a circuit is directly proportional to the voltage impressed across it, for any given temperature. Ohm expressed his discovery in the form of a simple equation, describing how voltage, current, and resistance interrelate:

In this algebraic expression, voltage (E) is equal to current (I) multiplied by resistance (R). Using algebra techniques, we can manipulate this equation into two variations, solving for I and for R, respectively:

Let’s see how these equations might work to help us analyze simple circuits:

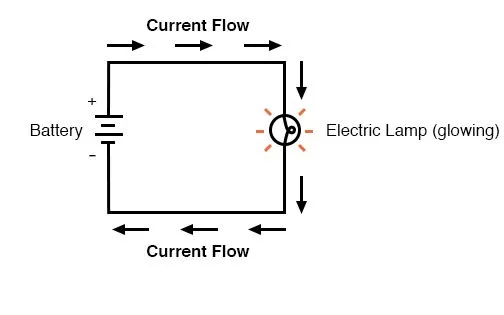

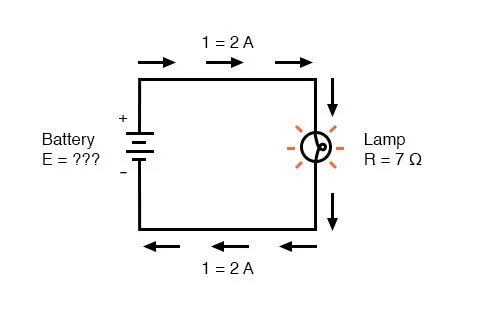

In the above circuit, there is only one source of voltage (the battery, on the left) and only one source of resistance to current (the lamp, on the right). This makes it very easy to apply Ohm’s Law. If we know the values of any two of the three quantities (voltage, current, and resistance) in this circuit, we can use Ohm’s Law to determine the third.

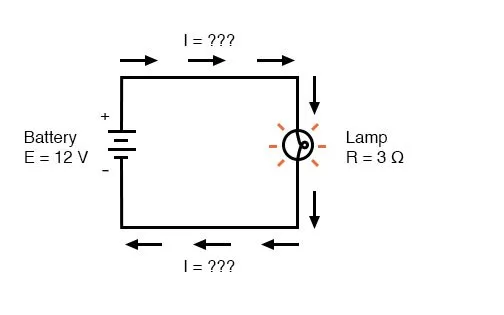

In this first example, we will calculate the amount of current (I) in a circuit, given values of voltage (E) and resistance (R):

What is the amount of current (I) in this circuit?

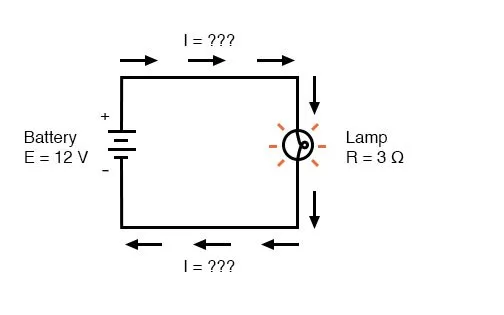

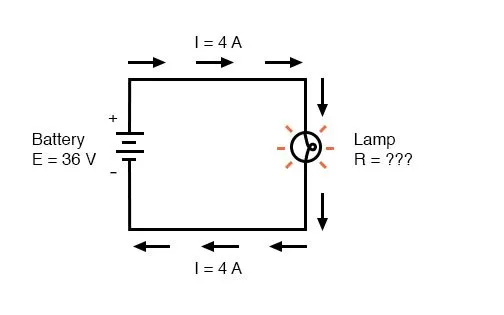

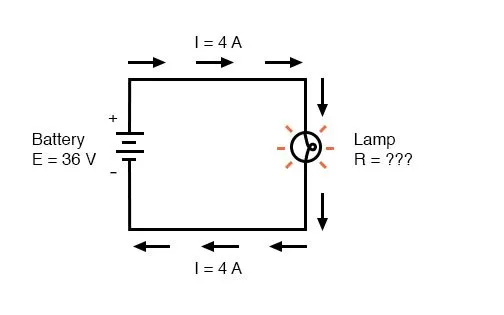

In this second example, we will calculate the amount of resistance (R) in a circuit, given values of voltage (E) and current (I):

What is the amount of resistance (R) offered by the lamp?

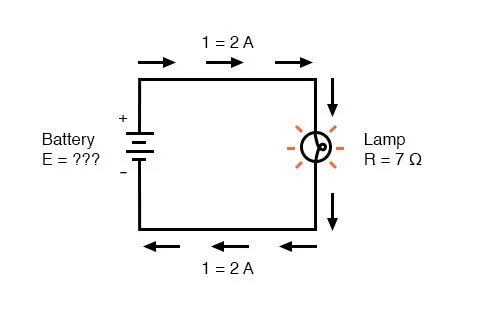

In the last example, we will calculate the amount of voltage supplied by a battery, given values of current (I) and resistance (R):

What is the amount of voltage provided by the battery?

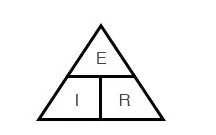

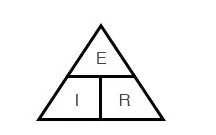

Ohm’s Law is a very simple and useful tool for analyzing electric circuits. It is used so often in the study of electricity and electronics that it needs to be committed to memory by the serious student. For those who are not yet comfortable with algebra, there’s a trick to remembering how to solve for anyone quantity, given the other two. First, arrange the letters E, I, and R in a triangle like this:

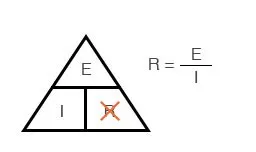

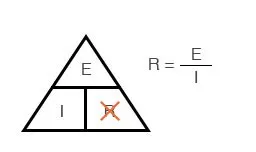

If you know E and I, and wish to determine R, just eliminate R from the picture and see what’s left:

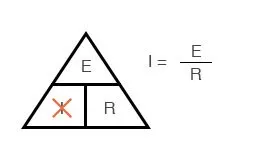

If you know E and R, and wish to determine I, eliminate I and see what’s left:

Lastly, if you know I and R, and wish to determine E, eliminate E and see what’s left:

Eventually, you’ll have to be familiar with algebra to seriously study electricity and electronics, but this tip can make your first calculations a little easier to remember. If you are comfortable with algebra, all you need to do is commit E=IR to memory and derive the other two formulae from that when you need them!