Cracking methodologies

Thermal cracking

Modern high-pressure thermal cracking operates at absolute pressures of about 7,000 kPa. An overall process of disproportionation can be observed, where "light", hydrogen-rich products are formed at the expense of heavier molecules which condense and are depleted of hydrogen. The actual reaction is known as homolytic fission and produces alkenes, which are the basis for the economically important production of polymers.[citation needed]

Thermal cracking is currently used to "upgrade" very heavy fractions or to produce light fractions or distillates, burner fuel and/or petroleum coke. Two extremes of the thermal cracking in terms of product range are represented by the high-temperature process called "steam cracking" or pyrolysis (ca. 750 °C to 900 °C or higher) which produces valuable ethylene and other feedstocks for the petrochemical industry, and the milder-temperature delayed coking (ca. 500 °C) which can produce, under the right conditions, valuable needle coke, a highly crystalline petroleum coke used in the production of electrodes for the steel and aluminium industries.[citation needed]

William Merriam Burton developed one of the earliest thermal cracking processes in 1912 which operated at 700–750 °F (370–400 °C) and an absolute pressure of 90 psi (620 kPa) and was known as the Burton process. Shortly thereafter, in 1921, C.P. Dubbs, an employee of the Universal Oil Products Company, developed a somewhat more advanced thermal cracking process which operated at 750–860 °F (400–460 °C) and was known as the Dubbs process.[6] The Dubbs process was used extensively by many refineries until the early 1940s when catalytic cracking came into use.[citation needed]

Steam cracking

Steam cracking is a petrochemical process in which saturated hydrocarbons are broken down into smaller, often unsaturated, hydrocarbons. It is the principal industrial method for producing the lighter alkenes (or commonly olefins), including ethene (or ethylene) and propene (or propylene). Steam cracker units are facilities in which a feedstock such as naphtha, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), ethane, propane or butane is thermally cracked through the use of steam in a bank of pyrolysis furnaces to produce lighter hydrocarbons.

In steam cracking, a gaseous or liquid hydrocarbon feed like naphtha, LPG or ethane is diluted with steam and briefly heated in a furnace without the presence of oxygen. Typically, the reaction temperature is very high, at around 850 °C, but the reaction is only allowed to take place very briefly. In modern cracking furnaces, the residence time is reduced to milliseconds to improve yield, resulting in gas velocities up to the speed of sound. After the cracking temperature has been reached, the gas is quickly quenched to stop the reaction in a transfer line heat exchanger or inside a quenching header using quench oil.[citation needed]

The products produced in the reaction depend on the composition of the feed, the hydrocarbon-to-steam ratio, and on the cracking temperature and furnace residence time. Light hydrocarbon feeds such as ethane, LPGs or light naphtha give product streams rich in the lighter alkenes, including ethylene, propylene, and butadiene. Heavier hydrocarbon (full range and heavy naphthas as well as other refinery products) feeds give some of these, but also give products rich in aromatic hydrocarbons and hydrocarbons suitable for inclusion in gasoline or fuel oil.[citation needed]

A higher cracking temperature (also referred to as severity) favors the production of ethene and benzene, whereas lower severity produces higher amounts of propene, C4-hydrocarbons and liquid products. The process also results in the slow deposition of coke, a form of carbon, on the reactor walls. This degrades the efficiency of the reactor, so reaction conditions are designed to minimize this. Nonetheless, a steam cracking furnace can usually only run for a few months at a time between de-cokings. Decokes require the furnace to be isolated from the process and then a flow of steam or a steam/air mixture is passed through the furnace coils. This converts the hard solid carbon layer to carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. Once this reaction is complete, the furnace can be returned to service.[citation needed]

Fluid Catalytic cracking

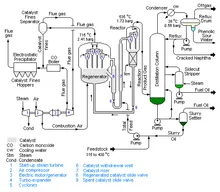

Schematic flow diagram of a fluid catalytic cracker

The catalytic cracking process involves the presence of solid acid catalysts, usually silica-alumina and zeolites. The catalysts promote the formation of carbocations, which undergo processes of rearrangement and scission of C-C bonds. Relative to thermal cracking, cat cracking proceeds at milder temperatures, which saves energy. Furthermore, by operating at lower temperatures, the yield of alkenes is diminished. Alkenes cause instability of hydrocarbon fuels.

Fluid catalytic cracking is a commonly used process, and a modern oil refinery will typically include a cat cracker, particularly at refineries in the US, due to the high demand for gasoline. The process was first used around 1942 and employs a powdered catalyst. During WWII, the Allied Forces had plentiful supplies of the materials in contrast to the Axis Forces, which suffered severe shortages of gasoline and artificial rubber. Initial process implementations were based on low activity alumina catalyst and a reactor where the catalyst particles were suspended in a rising flow of feed hydrocarbons in a fluidized bed.[citation needed]

In newer designs, cracking takes place using a very active zeolite-based catalyst in a short-contact time vertical or upward-sloped pipe called the "riser". Pre-heated feed is sprayed into the base of the riser via feed nozzles where it contacts extremely hot fluidized catalyst at 1,230 to 1,400 °F (666 to 760 °C). The hot catalyst vaporizes the feed and catalyzes the cracking reactions that break down the high-molecular weight oil into lighter components including LPG, gasoline, and diesel. The catalyst-hydrocarbon mixture flows upward through the riser for a few seconds, and then the mixture is separated via cyclones. The catalyst-free hydrocarbons are routed to a main fractionator for separation into fuel gas, LPG, gasoline, naphtha, light cycle oils used in diesel and jet fuel, and heavy fuel oil.[citation needed]

During the trip up the riser, the cracking catalyst is "spent" by reactions which deposit coke on the catalyst and greatly reduce activity and selectivity. The "spent" catalyst is disengaged from the cracked hydrocarbon vapors and sent to a stripper where it contacts steam to remove hydrocarbons remaining in the catalyst pores. The "spent" catalyst then flows into a fluidized-bed regenerator where air (or in some cases air plus oxygen) is used to burn off the coke to restore catalyst activity and also provide the necessary heat for the next reaction cycle, cracking being an endothermic reaction. The "regenerated" catalyst then flows to the base of the riser, repeating the cycle.[citation needed]

The gasoline produced in the FCC unit has an elevated octane rating but is less chemically stable compared to other gasoline components due to its olefinic profile. Olefins in gasoline are responsible for the formation of polymeric deposits in storage tanks, fuel ducts and injectors. The FCC LPG is an important source of C3-C4 olefins and isobutane that are essential feeds for the alkylation process and the production of polymers such as polypropylene.[citation needed]

Hydrocracking[edit]

Hydrocracking is a catalytic cracking process assisted by the presence of added hydrogen gas. Unlike a hydrotreater, hydrocracking uses hydrogen to break C-C bonds (hydrotreatment is conducted prior to hydrocracking to protect the catalysts in a hydrocracking process). In the year 2010, 265 × 106 tons of petroleum was processed with this technology. The main feedstock is vacuum gas oil, a heavy fraction of petroleum.

The products of this process are saturated hydrocarbons; depending on the reaction conditions (temperature, pressure, catalyst activity) these products range from ethane, LPG to heavier hydrocarbons consisting mostly of isoparaffins. Hydrocracking is normally facilitated by a bifunctional catalyst that is capable of rearranging and breaking hydrocarbon chains as well as adding hydrogen to aromatics and olefins to produce naphthenes and alkanes.

The major products from hydrocracking are jet fuel and diesel, but low sulphur naphtha fractions and LPG are also produced. All these products have a very low content of sulfur and other contaminants. It is very common in Europe and Asia because those regions have high demand for diesel and kerosene. In the US, fluid catalytic cracking is more common because the demand for gasoline is higher.

The hydrocracking process depends on the nature of the feedstock and the relative rates of the two competing reactions, hydrogenation and cracking. Heavy aromatic feedstock is converted into lighter products under a wide range of very high pressures (1,000-2,000 psi) and fairly high temperatures (750°-1,500 °F, 400-800 °C), in the presence of hydrogen and special catalysts.

The primary functions of hydrogen are, thus:

1. preventing the formation of polycyclic aromatic compounds if feedstock has a high paraffinic content,

2. reducing tar formation,

3. reducing impurities,

4. preventing buildup of coke on the catalyst,

5. converting sulfur and nitrogen compounds present in the feedstock to hydrogen sulfide and ammonia, and

6. achieving high cetane number fuel.