Steering system

On passenger cars, the driver must select the steering wheel angle to keep deviation from the desired course low. However, there is no definite functional relationship between the turning angle of the steering wheel made by the driver and the change in driving direction, because the correlation of the following is not linear.

· turns of the steering wheel;

· alteration of steer angle at the front wheels;

· development of lateral tyre forces;

· alteration of driving direction.

This results from elastic compliance in the components of the chassis. To move a vehicle, the driver must continually adjust the relationship between turning the steering wheel and the alteration in the direction of travel. To do so, the driver will monitor a wealth of information, going far beyond the visual perceptive faculty (visible deviation from desired direction). These factors would include for example, the roll inclination of the body, the feeling of being held steady in the seat (transverse acceleration) and the self-centring torque the driver will feel through the steering wheel. The most important information the driver receives comes via the steering moment or torque which provides him with feedback on the forces acting on the wheels.

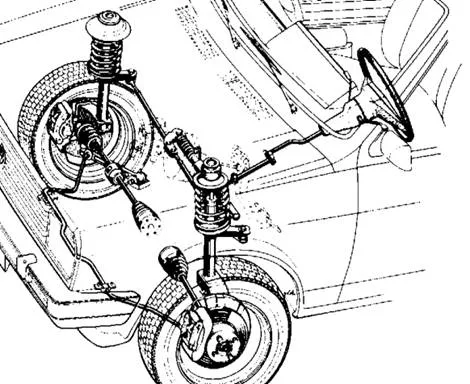

It is therefore the job of the steering system to convert the steering wheel angle into as clear a relationship as possible to the steering angle of the wheels and to convey feedback about the vehicle’s state of movement back to the steering wheel. This passes on the actuating moment applied by the driver, via the steering column to the steering gear 1 which converts it into pulling forces on one side and pushing forces on the other, these being transferred to the steering arms 3 via the tie rods 2. These are fixed on both sides to the steering knuckles and cause a turning movement until the required steering angle has been reached. Rotation is around the steering axis EG, also called kingpin inclination, pivot or steering rotation axis.

Damper strut front axle of a VW Polo (up to 1994) with ‘steering gear’, long tie rods and a ‘sliding clutch’ on the steering tube; the end of the tube is stuck onto the pinion gear and fixed with a clamp. The steering arms, which consist of two half shells and point backwards, are welded to the damper strut outer tube. An ‘additional weight’ (harmonic damper) sits on the longer right drive shaft to damp vibrations. The anti-roll bar carries the lower control arm. To give acceptable ground clearance, the back of it was designed to be higher than the fixing points on the control arms. The virtual pitch axis is therefore in front of the axle and the vehicle’s front end is drawn downwards when the brakes are applied.