|

|

skirtboards

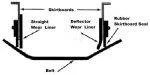

To retain the material on the belt-after it leaves the loading chute and until it reaches belt speed-skirtboards are necessary. These skirtboards usually are an extension of the sides of the loading chute and extend parallel to one another for some distance along the conveyor belt. The skirtboards normally are made of metal, although wood sometimes is used. The lower edges of the skirtboards are positioned some distance above the belt. The gap between the skirtboard bottom edge and the belt surface is sealed by a rectangular rubber strip, attached or clamped to the exterior of the skirtboard. See Figure 1, below.

If the material conveyed contains hard lumps, particularly lumps with sharp edges, the gap between the bottom of the skirtboards and the belt should be made to increase uniformly in the direction of belt travel. Any lump forced under the skirtboard edge will quickly free itself as the belt moves forward, and thus not abrade the belt.

When handling a mixture of large lumps and fines or only sized lumps, the skirtboards sometimes are not made parallel to each other but are splayed out in the direction of the belt travel.

Such an arrangement prevents lumps from jamming between the skirtboards. Frequently, the back plate of such a set of skirtboards is made in a curve instead of straight across the belt. Splayed skirtboards should be kept as short as possible because the rubber edging is difficult to fit to the contour of the troughed belt, both initially and during subsequent maintenance.

Commonly used proportions and details of skirtboards and rubber strip edgings are as follows:

Spacing of skirtboards. The maximum distance between skirtboards customarily is two-thirds the width of a troughed belt, (0.666b). However, it is desirable, when possible, to reduce this spacing to one-half the width of the troughed belt (0.500b), especially for free flowing materials such as grain.

On flat belts, depending on how well the belt is trained centrally, how well it is supported by idlers or a loading plate beneath the belt, and how effectively the rubber edging seal is maintained, the space between the skirtboards may be but a few inches less than the belt width. Such spacing commonly is used when handling damp or prepared molding sand, or similar materials which do not tend to slump much upon leaving the end off lie loading area.

Length of skirtboards. Usually, when, the loading is in the direction of the troughed belt travel, the skirtboard length is a function of the difference between the loading material velocity - at the moment the material reaches the belt - and the belt velocity. For the installation where this difference is small, the length of the skirtboards can safely be 600mm for each 0.5 m/s of belt speed, but not less than 900mm. Skirtboards preferably should terminate above an idler rather than between idlers.

Height of skirtboards. The height of skirtboards must be sufficient to contain the material volume as it is loaded on the belt. Table 1, below indicates the accepted reasonable practice for skirtboard height, for 20, 35, and 45 three-equal-roll troughing idlers.

Skirtboard clearance over belt. The metal (or wood) portion of the skirtboards should not come closer than 25.4mm to the belt surface. This clearance preferably should increase uniformly in the direction of belt travel. As previously explained, this steadily increasing gap permits lumps or foreign objects to move forward without becoming jammed between the lower edge of the skirtboards and the belt.

Greater clearance may be used, but this necessitates wider and thicker strips, particularly for long skirtboards.

Skirtboarding rubber edging. To prevent leakage of fines through the clearance between the lower edge of the skirtboards and the moving belt, it is common practice to edge the skirtboard exterior with long, flat strips of 6.35mm to 12.7mm thick solid rubber. These strips can be bolted or clamped to the skirtboard in such a manner as to permit the strip to be adjusted to rest lightly on the belt surface, both initially and after wear has taken place. See Figure 1.

Such edging should be of solid rubber of at least 60 to 100 durometer hardness. And, it should contain no fabric to pick up and retain abrasive particles, thus avoiding the abrasion of the belt cover. Strips of old rubber belting never should be used for edging skirtboards. The width of the rubber-edging strips will depend upon the manner they are attached to the skirtboard and upon the wear allowance.

Rubber edging may be installed vertically or at air angle. Edging installed at an angle provides a better seal between idlers as the belt flexes under load. However, care must be exercised in design to combine good sealing with minimum belt cover wear.

Where the characteristics of the material permit-such as uniform lump size greater than 25.4mm and no fines-the rubber skirtboard edging may be safely omitted, but only if the skirtboards are not too close to the edge of the belt. Omission of rubber skirtboard edging does eliminate some wear and grooving of the belt cover.

When splayed skirtboards are used, the rubber edging bears against a wider portion of the belt cover, thus reducing the tendency to form grooves in the belt cover.

Rubber skirtboard edging should be adjusted frequently so that the edging just touches the belt surface. Forcing the edging hard against the belt cover will not only groove the belt cover but will also require additional power to move the belt. On conveyors with continuous skirtboards, improper pressure of rubber skirtboard edging may overload the belt conveyor driving motor.

Skirtboard covers. Suitably high skirtboards may be covered to minimise dusting. The top edges of the skirtboards may be flanged, exteriorly, and the cover fastened to these flanges.

If skirtboard covers are used, especially on skirtboards for inclined belt conveyors, the portion of the cover adjacent to the feed chute should be generously slanted to meet the chute. This is necessary to make, room for material which is not yet moving at belt speed and thus avoid a jam in the material flow at the end of the feed chute.

Skirtboards for intermediate loading points. Where a belt is loaded at more than one point in the belt length, care must be used in the arrangement of the skirtboards at the intermediate loading points. Because the load of material tends to flatten and spread on the belt, skirtboards at these intermediate loading points must be designed to let the previously loaded material pass freely. Usually, intermediate-loading-point skirtboards are placed closer together, with a generous clearance above the previous load surface. Rubber edging is omitted from intermediate-loading-point skirtboards as it serves no purpose.

Spillage may occur at intermediate loading points, even with the most careful design of the skirtboards, because of fluctuating initial loading. Dusting at intermediate loading points is almost inevitable

Often when intimidate loading points are relatively close together, it is better to continue the skirtboards between the loading points than to hazard the use of relatively short lengths at the intermediate loading points. Continuous skirtboards are good insurance against spillage.

Sometimes the use of a wider-than-normal belt or a more deeply troughed belt will facilitate loading without spillage at intermediate loading points.

Friction against skirtboards. The additional belt pull required to over come the friction of the rubber skirtboard edging.Conveyor accessories such as skirtboards usually increase belt conveyor power requirements and as such adequate allowances should be made depending on the length of installed skirts and number of feed points.