Mics used: Two omnidirectional mics, usually small diaphragm condensers

Mics used: Two omnidirectional mics, usually small diaphragm condensersWhen you first learn about the power of microphone positioning, you’re instantly fascinated.

Could a difference of an inch in positioning really make that much a difference in sound?

As you eventually come to find out…absolutely it does.

And once you discovered that, you start to wonder – what else have I been missing out on all this time?

Well, I’ll tell you. It’s called stereo recording.

And it’s the real secret professionals use to create that awesome sound that’s had you baffled up until now.

Stereo recording is a technique involving the use of two microphones to simultaneously record one instrument. The mono signals from each microphone are assigned to the left and right channels of a stereo track to create a sense of width in the recording.

The stereo effect is created in this technique from the slight difference in sound between the left and right channels of the studio monitors. This difference in sound is observed in the following two ways:

· Difference in timing – By placing the microphones at different locations, the sound from the instrument will arrive at each microphone at a slightly different time. A difference of just a few milliseconds is enough to create a stereo effect.

· Difference in frequency balance – By angling the microphone in different directions in relation to the instrument, each microphone will pick up a slightly different balance of frequencies. The greater the angle, the more exaggerated the stereo effect will be.

When one mic is heard through the left monitor, and the other mic through the right, it creates a pleasant sense of width that is absent in a mono recording.

So how do you do it?

Here is a list of the 5 most useful stereo recording techniques you should know. For each one, I’ll explain:

· the type of mic required, (including the microphone polar pattern)

· how to position them for recording

· how to mix the two signals together

· how it should sound once completed

Let’s start off with the simplest and most common of the five techniques:

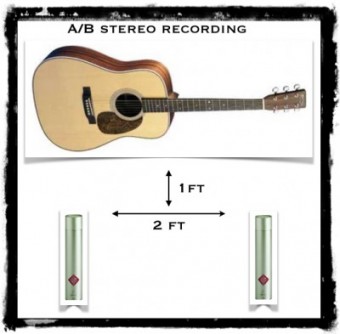

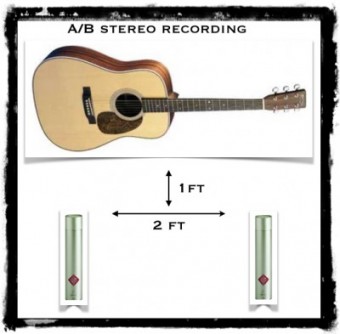

Mics used: Two omnidirectional mics, usually small diaphragm condensers

Mics used: Two omnidirectional mics, usually small diaphragm condensers

Positioning: Point both mics toward the instrument, at a distance of a foot, and spaced two feet apart.

When experimenting with this technique, try making adjustments to both the distance of the mics from the instrument, as well as the distance of the mics from each other.

How to mix the signals: The mono signals from each microphone are assigned to the left and right channels of a stereo track to create a sense of width in the recording.

How it should sound: The stereo image is created because the time of arrival at each microphone is slightly staggered. The frequency balance is different as well, which will provide an added level of stereo width.

The downside of A/B stereo recording is that because of the timing offset between each microphone, you will be likely to have issues with phase cancellation when combining the stereo signal to mono.

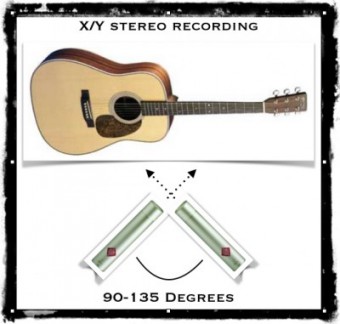

Mics used: Two directional mics, usually small diaphragm condensers

Mics used: Two directional mics, usually small diaphragm condensers

Positioning: at an angle between 90-135 degrees so that their capsules coincide at a single point. The wider the angle, the wider the stereo image.

How to Mix the Signals: (same as A/B stereo recording)

How it should sound: Compared to A/B stereo recording, this technique will have less of a stereo effect. The reason is that since both microphones are positioned at the same point in space, there will be no differences in timing.

The entire stereo effect will be created from the differences in frequency balance. The upside to this is there are no issues with mono phase cancellation either.

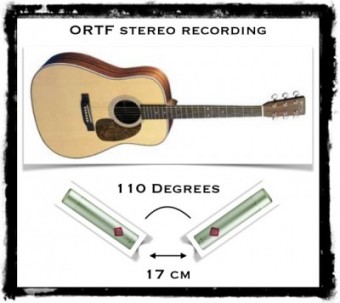

Mics used: Two directional mics, usually small diaphragm condensers

Mics used: Two directional mics, usually small diaphragm condensers

Positioning: Spread outward at an angle of about 110 degrees, with the capsules spaced 17cm apart.

How to mix the signals: (same as A/B stereo recording)

How it should sound: The technique is basically a combination of the previous two. The microphones are physically spaced apart, like with A/B recording, which will yield a wider stereo image. Then it uses directional mics, like with X/Y recording, so it should pick up less of the ambient room sound.

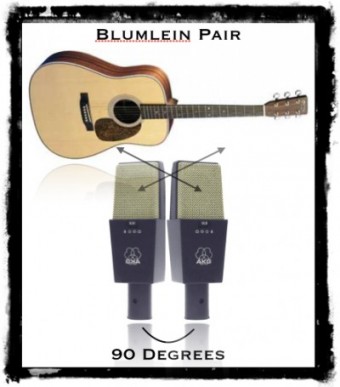

Mics used: two figure 8 (bi directional) mics

Mics used: two figure 8 (bi directional) mics

Positioning: (same as X/Y technique)

How to mix the signals: (same as X/Y technique)

How it should sound: Compared to the X/Y technique, the Blumlein Pair technique captures a greater portion of the room sound and adds a bit more ambience to the stereo image, thanks to the use of the figure 8 mics.

Mics used: One small diaphragm condenser mic – either cardioid OR omnidirectional.

Mics used: One small diaphragm condenser mic – either cardioid OR omnidirectional.

One large diaphragm condenser mic – MUST BE FIGURE 8

Positioning: The figure 8 mic is placed sideways at a 90 degree angle from the instrument. This mic will record sound on both sides and will function as the “side” in the term mid/side.

The other mic is positioned on top or below the figure 8 mic, and is pointed directly toward the instrument. It will function as the “mid” in the term mid/side.

How to mix the signals: This part is complicated. Follow the steps carefully.

1. Duplicate the “side” channel

2. Reverse the polarity of the duplicated channel

3. Combine the two side channels onto one stereo track

4. Mix in the mid channel with stereo side channels to adjust the width. The greater level of the sides compared to the mid, the greater the stereo width.

How it should sound: Mid side recording may be complicated, but it offers all the advantages of the other 3 techniques, without the downsides.

· It offers the added stereo width of the A/B technique

· It offers the mono compatibility of the X/Y technique

· And it allows you (if you want) to increase the room ambiance to something resembling the Blumlein Pair technique.

While stereo recording applied in the right situations can improve the quality and interest of your mixes by leaps and bounds, there are some situations when it is simply not appropriate.

Certain instruments that you record will sound better in mono almost 100 percent of the time.

And here are the most common 4:

1. Lead Vocals – which is expected to be located at center stage. For that reason, it is typically recorded in mono.

2. Snare Drum – which is also expected to be at center stage. It would sound quite odd if it was located off to one side of the stereo image.

3. Kick Drum – which should be recorded in mono because its heavy low frequency content requires a lot of power to reproduce on speakers. In order to get the maximum output from the mix, it’s best that the work be shared equally by both the left and right channels.

4. Bass – which is also made up mainly of low frequencies so it generally works better in mono as well. Another reason for this rule is that our ears are not good at obtaining directional information from low frequencies, so it makes little sense to create a stereo image for any low frequency instrument.