The Laws of Planetary Motion

At about the time that Galileo was beginning his experiments with falling bodies, the efforts of two other scientists dramatically advanced our understanding of the motions of the planets. These two astronomers were the observer Tycho Brahe and the mathematician Johannes Kepler. Together, they placed the speculations of Copernicus on a sound mathematical basis and paved the way for the work of Isaac Newton in the next century.

Tycho Brahe’s Observatory

Three years after the publication of Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus, Tycho Brahe was born to a family of Danish nobility. He developed an early interest in astronomy and, as a young man, made significant astronomical observations. Among these was a careful study of what we now know was an exploding star that flared up to great brilliance in the night sky. His growing reputation gained him the patronage of the Danish King Frederick II, and at the age of 30, Brahe was able to establish a fine astronomical observatory on the North Sea island of Hven (Figure 1). Brahe was the last and greatest of the pre-telescopic observers in Europe.

Figure 1: Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) and Johannes Kepler (1571–1630). (a) A stylized engraving shows Tycho Brahe using his instruments to measure the altitude of celestial objects above the horizon. The large curved instrument in the foreground allowed him to measure precise angles in the sky. Note that the scene includes hints of the grandeur of Brahe’s observatory at Hven. (b) Kepler was a German mathematician and astronomer. His discovery of the basic laws that describe planetary motion placed the heliocentric cosmology of Copernicus on a firm mathematical basis.

At Hven, Brahe made a continuous record of the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets for almost 20 years. His extensive and precise observations enabled him to note that the positions of the planets varied from those given in published tables, which were based on the work of Ptolemy. These data were extremely valuable, but Brahe didn’t have the ability to analyze them and develop a better model than what Ptolemy had published. He was further inhibited because he was an extravagant and cantankerous fellow, and he accumulated enemies among government officials. When his patron, Frederick II, died in 1597, Brahe lost his political base and decided to leave Denmark. He took up residence in Prague, where he became court astronomer to Emperor Rudolf of Bohemia. There, in the year before his death, Brahe found a most able young mathematician, Johannes Kepler, to assist him in analyzing his extensive planetary data.

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler was born into a poor family in the German province of Württemberg and lived much of his life amid the turmoil of the Thirty Years’ War (see Figure 1). He attended university at Tubingen and studied for a theological career. There, he learned the principles of the Copernican system and became converted to the heliocentric hypothesis. Eventually, Kepler went to Prague to serve as an assistant to Brahe, who set him to work trying to find a satisfactory theory of planetary motion—one that was compatible with the long series of observations made at Hven. Brahe was reluctant to provide Kepler with much material at any one time for fear that Kepler would discover the secrets of the universal motion by himself, thereby robbing Brahe of some of the glory. Only after Brahe’s death in 1601 did Kepler get full possession of the priceless records. Their study occupied most of Kepler’s time for more than 20 years.

Through his analysis of the motions of the planets, Kepler developed a series of principles, now known as Kepler’s three laws, which described the behavior of planets based on their paths through space. The first two laws of planetary motion were published in 1609 in The New Astronomy. Their discovery was a profound step in the development of modern science.

The First Two Laws of Planetary Motion

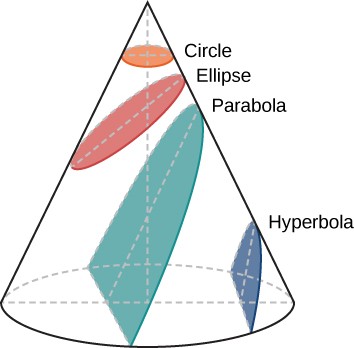

Figure 2: Conic Sections. The circle, ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola are all formed by the intersection of a plane with a cone. This is why such curves are called conic sections.

The path of an object through space is called its orbit. Kepler initially assumed that the orbits of planets were circles, but doing so did not allow him to find orbits that were consistent with Brahe’s observations. Working with the data for Mars, he eventually discovered that the orbit of that planet had the shape of a somewhat flattened circle, or ellipse. Next to the circle, the ellipse is the simplest kind of closed curve, belonging to a family of curves known as conic sections (Figure 2).

You might recall from math classes that in a circle, the center is a special point. The distance from the center to anywhere on the circle is exactly the same. In an ellipse, the sum of the distance from two special points inside the ellipse to any point on the ellipse is always the same. These two points inside the ellipse are called its foci (singular: focus), a word invented for this purpose by Kepler.

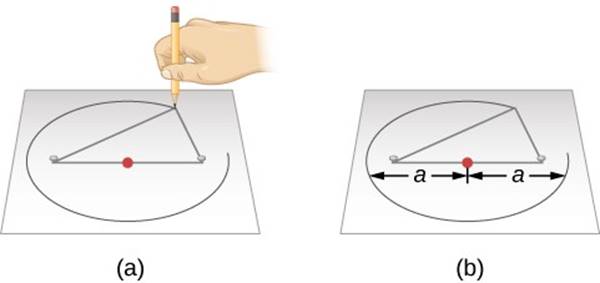

This property suggests a simple way to draw an ellipse (Figure 3). We wrap the ends of a loop of string around two tacks pushed through a sheet of paper into a drawing board, so that the string is slack. If we push a pencil against the string, making the string taut, and then slide the pencil against the string all around the tacks, the curve that results is an ellipse. At any point where the pencil may be, the sum of the distances from the pencil to the two tacks is a constant length—the length of the string. The tacks are at the two foci of the ellipse.

The widest diameter of the ellipse is called its major axis. Half this distance—that is, the distance from the center of the ellipse to one end—is the semimajor axis, which is usually used to specify the size of the ellipse. For example, the semimajor axis of the orbit of Mars, which is also the planet’s average distance from the Sun, is 228 million kilometers.

Figure 3: Drawing an Ellipse. (a) We can construct an ellipse by pushing two tacks (the white objects) into a piece of paper on a drawing board, and then looping a string around the tacks. Each tack represents a focus of the ellipse, with one of the tacks being the Sun. Stretch the string tight using a pencil, and then move the pencil around the tacks. The length of the string remains the same, so that the sum of the distances from any point on the ellipse to the foci is always constant. (b) In this illustration, each semimajor axis is denoted by a. The distance 2a is called the major axis of the ellipse.

The shape (roundness) of an ellipse depends on how close together the two foci are, compared with the major axis. The ratio of the distance between the foci to the length of the major axis is called the eccentricity of the

ellipse.

If the foci (or tacks) are moved to the same location, then the distance between the foci would be zero. This means that the eccentricity is zero and the ellipse is just a circle; thus, a circle can be called an ellipse of zero eccentricity. In a circle, the semimajor axis would be the radius.

Next, we can make ellipses of various elongations (or extended lengths) by varying the spacing of the tacks (as long as they are not farther apart than the length of the string). The greater the eccentricity, the more elongated is the ellipse, up to a maximum eccentricity of 1.0, when the ellipse becomes “flat,” the other extreme from a circle.

The size and shape of an ellipse are completely specified by its semimajor axis and its eccentricity. Using Brahe’s data, Kepler found that Mars has an elliptical orbit, with the Sun at one focus (the other focus is empty). The eccentricity of the orbit of Mars is only about 0.1; its orbit, drawn to scale, would be practically indistinguishable from a circle, but the difference turned out to be critical for understanding planetary motions.

Kepler generalized this result in his first law and said that the orbits of all the planets are ellipses. Here was a decisive moment in the history of human thought: it was not necessary to have only circles in order to have an accepTable cosmos. The universe could be a bit more complex than the Greek philosophers had wanted it to be.

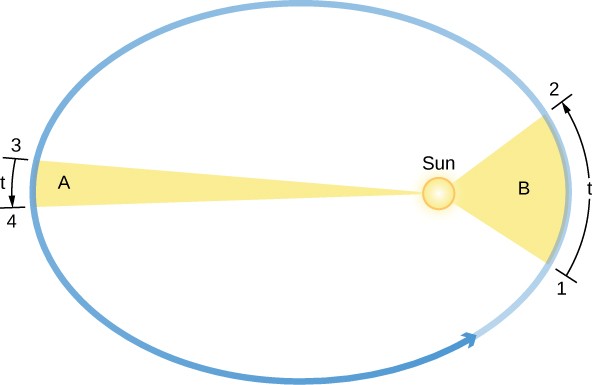

Kepler’s second law deals with the speed with which each planet moves along its ellipse, also known as its orbital speed. Working with Brahe’s observations of Mars, Kepler discovered that the planet speeds up as it comes closer to the Sun and slows down as it pulls away from the Sun. He expressed the precise form of this relationship by imagining that the Sun and Mars are connected by a straight, elastic line. When Mars is closer to the Sun (positions 1 and 2 in Figure 4), the elastic line is not stretched as much, and the planet moves rapidly. Farther from the Sun, as in positions 3 and 4, the line is stretched a lot, and the planet does not move so fast. As Mars travels in its elliptical orbit around the Sun, the elastic line sweeps out areas of the ellipse as it moves (the colored regions in our figure). Kepler found that in equal intervals of time (t), the areas swept out in space by this imaginary line are always equal; that is, the area of the region B from 1 to 2 is the same as that of region A from 3 to 4.

If a planet moves in a circular orbit, the elastic line is always stretched the same amount and the planet moves at a constant speed around its orbit. But, as Kepler discovered, in most orbits that speed of a planet orbiting its star (or moon orbiting its planet) tends to vary because the orbit is elliptical.

Figure 4: Kepler’s Second Law: The Law of Equal Areas. The orbital speed of a planet traveling around the Sun (the circular object inside the ellipse) varies in such a way that in equal intervals of time (t), a line between the Sun and a planet sweeps out equal areas (A and B). Note that the eccentricities of the planets’ orbits in our solar system are substantially less than shown here.