The History of Archaeology - The First Archaeologists

The history of archaeology as a study of the ancient past has its beginnings at least as early as the Mediterranean Bronze Age, with the first archaeological investigations of ruins.

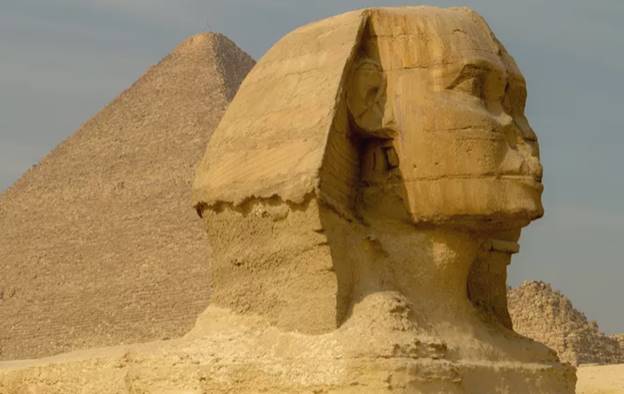

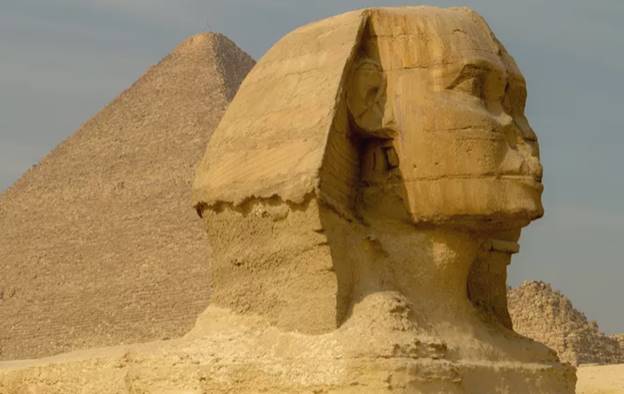

Archaeology as a scientific study is only about 150 years old. Interest in the past, however, is much older than that. If you stretch the definition enough, probably the earliest probe into the past was during New Kingdom Egypt (ca 1550–1070 BCE), when the pharaohs excavated and reconstructed the Sphinx, itself originally built during the 4th Dynasty (Old Kingdom, 2575–2134 BCE) for the Pharaoh Khafre. There are no written records to support the excavation--so we don't know which of the New Kingdom pharaohs asked for the Sphinx to be restored—but physical evidence of the reconstruction exists, and there are ivory carvings from earlier periods that indicate the Sphinx was buried in sand up to its head and shoulders before the New Kingdom excavations.

The First Archaeologists

Tradition has it that the first recorded archaeological dig was operated by Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon who ruled between 555–539 BCE. Nabonidus' contribution to the science of the past is the unearthing of the foundation stone of a building dedicated to Naram-Sin, the grandson of the Akkadian king Sargon the Great. Nabonidus overestimated the age of the building foundation by 1,500 years—Naram Sim lived about 2250 BCE, but, heck, it was the middle of the 6th century BCE: there were no radiocarbon dates. Nabonidus was, frankly, deranged (an object lesson for many an archaeologist of the present), and Babylon was eventually conquered by Cyrus the Great, founder of Persepolis and the Persian empire.

To find the modern equivalent of Nabonidus, ne'er do well well-born British citizen John Aubrey (1626–1697) is a good candidate. He discovered the stone circle of Avebury in 1649 and completed the first good plan of Stonehenge. Intrigued, he wandered the British countryside from Cornwall to the Orkneys, visiting and recording all the stone circles he could find, ending up 30 years later with his Templa Druidum (Temples of the Druids)—he was misguided about the attribution.

Excavating Pompeii and Herculaneum

Most of the early excavations were either religious crusades of one sort or another or treasure hunting by and for elite rulers, pretty consistently right up until the second study of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The original excavations at Herculaneum were simply treasure-hunting, and in the early decades of the 18th century, some of the intact remains covered by nearly 60 feet of volcanic ash and mud 1500 years before were destroyed in an attempt to find "the good stuff." But, in 1738, Charles of Bourbon, King of the Two Sicilies and founder of the House of Bourbon, hired antiquarian Marcello Venuti to reopen the shafts at Herculaneum. Venuti supervised the excavations, translated the inscriptions, and proved that the site was indeed Herculaneum. His 1750 work, "A Description of the First Discoveries of the Ancient City of Heraclea," is still in print. Charles of Bourbon is also known for his palace, the Palazzo Reale in Caserta.