Chandragupta II

Definition

Chandragupta II (c. 375 CE - 413/14 CE) was the next great Gupta emperor after his father Samudragupta (335/350 - 370/380 CE). He proved to be an able ruler and conqueror with many achievements to his credit. He came to be known by his title Vikramaditya (Sanskrit: "Sun of Power"). He carried on the legacy of Samudragupta and contributed his share towards sustaining an extensive empire that carved out a place for itself in history.

Succession

Chandragupta’s accession to the throne was not smooth, as he had to depose his brother Ramagupta. Samudragupta had been succeeded by his eldest son Ramagupta (370-375 CE). The existence of coins and inscriptions recording the installation of images in a Jaina temple in central India by Maharajadhiraja (Sanskrit: "Lord of Great Kings") Ramagupta attest to the existence of this king. The Gupta inscriptions do not mention Ramagupta, for the simple reason that going by the tradition of ancient Indian genealogies, deposed kings are hardly mentioned as the focus is on the king who deposed him and his successors. Thus, "since the succession passed to Chandragupta and his sons, Ramagupta is ignored" (Singh, 479).

There is no historical evidence discovered as yet as to how and why Chandragupta followed his brother on the throne. The sole mention of it occurs only in literary sources, with the foremost being the Sanskrit play Devichandraguptam ("Devi and Chandragupta") written by the celebrated playwright Vishakhadatta sometime between the 4th and 8th centuries CE. According to the story in the play, Ramagupta was a weak and immoral king. Unable to face the might of the Shaka (Scythian) king, he agreed to the terms of surrender which included also the surrender of his wife, the Chief Queen Dhruvadevi (Devi or Dhruvasvamini) to the enemy king. His younger brother Chandragupta could not stand this disgrace. Disguising himself as the Queen, he reached the enemy camp and killed the Shaka king in his sleep. Ramagupta was petrified at this incident and greatly feared a heavy Shaka backlash. Disgusted by his brother’s cowardice, Chandragupta eventually deposed and killed him. He then married Dhruvadevi and ascended the throne.

Many historians maintain that it is not known as to "how far the story embodies genuine historical tradition" (Majumdar, 141). Nonetheless, the events as stated by the play continued to find reverberations in later literary texts including the Harshacharita or the biography of Emperor Harshavardhana or Harsha (606 – 647 CE) of the Pushyabhuti Dynasty, written by his court poet Banabhatta or Bana (c. 7th century CE). Bana writes, "In his enemy’s city the king of the Shakas, while courting another’s wife, was butchered by Chandragupta concealed in his mistress’s dress" (Banabhatta, 194).

The inscriptions of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty (8th-10th century CE) of southern India also cite these happenings (mentions are made of a Gupta prince who killed his elder brother, and then seized his kingdom, marrying his queen), thus showing that these events or their knowledge was well part of public memory even in the 9th and 10th centuries CE. Historian RK Mookerji says that "the original story mentioned by Bana received additions and embellishments in later texts, literary and epigraphic" (Mookerji, 67). Chandragupta, historically, did have a queen named Dhruvadevi, who was the mother of his successor, Kumaragupta I (414-455 CE). Thus, it is quite probable that Vishakhadatta built up his plot around historical persons, based on what was known (or supposed) of them at his time, which perhaps included recollection of some enduring animosity between the two brothers over the throne, or possibly even over Dhruvadevi.

The historical importance of this play, however, lies in the establishment of the identity of Ramagupta - otherwise so completely dismissed by the official Gupta records - both as an actual person and as the successor of Samudragupta. This has helped historians view any inscriptions or other evidence associated with this name very closely, and try to figure out what had really happened in his reign. Most of the details are yet to be known.

Political Conditions

Samudragupta’s exertions had created a vast empire, and so "Chandragupta II was spared the difficult task of building up an empire" (Tripathi, 250). Samudragupta’s strategy was guided by the prevailing political and economic conditions. He realized that he could not control directly a vast empire from his capital and hence focused on annexing those kingdoms which lay on his borders. For the rest, only an acceptance of suzerainty would do while their own kings would be left to deal with issues of governance and administration. At the same time, being subordinate, they would not create challenges for the Guptas. Therefore, unlike the Mauryas (4th-2nd century BCE), the Gupta Empire under Samudragupta did not directly control many of its constituents. Samudragupta, thus, despite his conquests, did not create an all-India empire. Using his military power, he instead built up the political machinery in such a way that the Gupta suzerainty and paramountcy came to be acknowledged over most of the subcontinent and many kingdoms and republics regarded themselves as subordinate to the Gupta emperor.

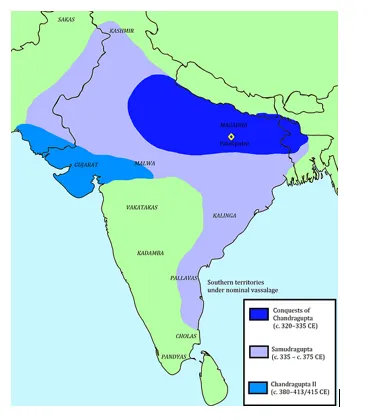

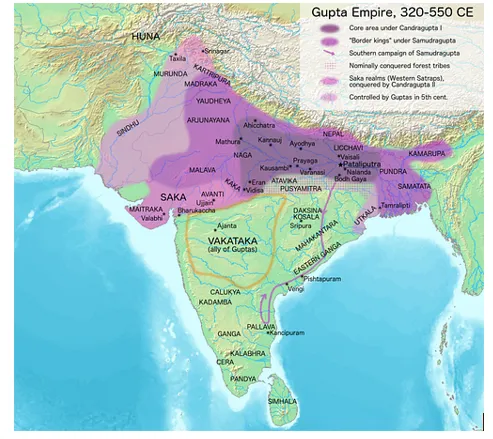

Gupta Empire and Conquests

by Javierfv1212 (CC BY-SA)

Given the time, with feudalism making rapid inroads, this was probably the best way to create a widespread empire. Direct control and a centralized system as under the Maurya Empire were no longer tenable. In the changed circumstances, the Guptas could not hope to exercise monopolistic control over the economy and hence could not have the vast resources necessary to run a bureaucratic empire with a vast military. The best idea, then, was to build a military mighty enough to cow down the enemy and keep him cowed. Able to garner suzerainty in such a manner, Samudragupta believed he could create and keep the peace necessary for his empire to prosper. At the same time, many of those subordinate dynasties would continue to grow as well but would be left alone as long as they did not challenge the Gupta power.

Chandragupta, in his time, felt the same way. For him, what remained was to either fight the remaining kings that had not been tackled by Samudragupta or to ally himself with the prominent dynasties that had retained their power and were ruling their own lands, and over time, could become strong enough to rival his might. He thus fought wherever possible and settled for peacemaking elsewhere.

Alliances

In keeping with the times, Chandragupta also applied his diplomatic skills to good use. The Guptas were the most prominent dynasty of their time, but there were others who were turning out to be quite powerful themselves. Since warfare was not always the best means to tackle them, often non-military means, particularly matrimonial matchmaking, were adopted to keep these powers in check, subdued, or taken as allies.

Extent of the Gupta Empire, 320-550 CE

by Avantiputra7 (CC BY-SA)

Chandragupta took as one of his queens Princess Kuberanaga, thus pacifying the strong Naga Dynasty ruling in parts of north-central India. Another power that needed attention was the Vakataka Dynasty of western India. This kingdom was strategically located, particularly from a campaign perspective, as its "geographical position could affect movements to its north against the Shaka satrapies of Gujarat and Saurashtra" (Mookerjee, 48). Chandragupta settled for a matrimonial alliance with the Vakatakas by marrying his and Kuberanaga’s daughter Prabhavatigupta to the Vakataka king Rudrasena II (380-385 CE). Upon the latter’s death, Prabhavatigupta became regent for her minor son, and many historians believe that through her Chandragupta extended his rule to the Vakataka kingdom as well, as Prabhavatigupta was ruling according to her father’s advice and guidance. The Gupta sway over the kingdom of Kuntala in southern India, for instance, was brought about "by the regency administration of Queen Prabhavatigupta seeking her father’s intervention which was further increased under the inefficient rule of her son given to a life of luxury and poetical preoccupation" (Mookerjee, 47).

Conquests & the Shaka Campaign

Chandragupta continued with Samudragupta’s expansionist policy and led campaigns into Bengal (eastern India) and Punjab (north-western India). The Shakas of western India (also known as the Western Satrapas) constituted the biggest threat to the Gupta Empire at this time. Chandragupta’s war was a protracted one and lasted nearly 20 years, with his coins first appearing in the region in 409 CE.

Though no historical evidence is available as yet in this regard, it is quite probable that Ramagupta may have realized the danger coming from the Shaka quarter, and planned on tackling them. Either the campaign never occurred or it simply fell through, and it was then that Prince Chandragupta chose to take up the initiative, which he did by eventually murdering the Shaka king. Unable to go further, he could have allowed the leaderless and demoralized Shaka troops to disperse and return, and who later probably regrouped under a new king. Ramagupta’s deposition, or the conditions of intrigue prevailing in the Gupta court, would have halted a follow-up action, and it was left to Chandragupta as the new emperor to now decide the course of action.

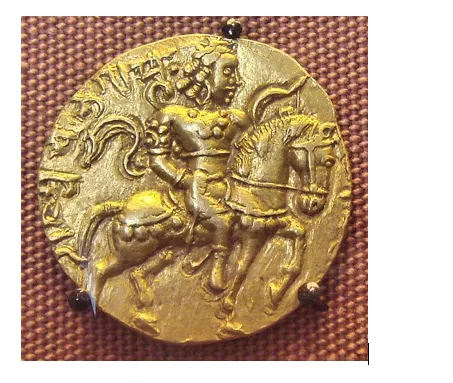

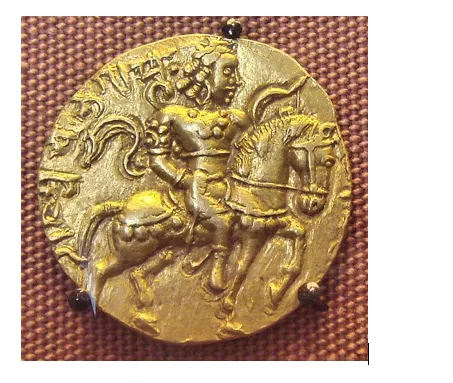

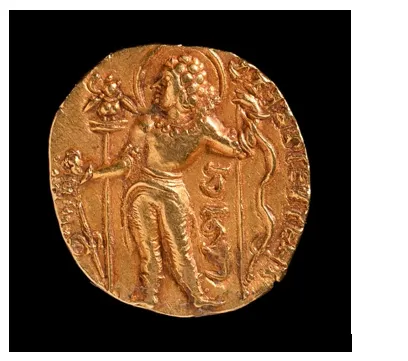

Gold Coin of Chandragupta II

by Ashley Van Haeften (CC BY)

Gupta inscriptions mention Chandragupta’s campaign against the Shakas as part of his ambition of world conquest (prithvijaya). The Vakataka alliance proved to be of use as access routes were gained and the emperor, working on improving and augmenting his army with greater numbers, marched on. His victories on the battlefield decided the final outcome, and it is extremely improbable that he killed the enemy king in disguise, as it would have been very degrading for an emperor to do the work of a lowly assassin.