Maths and Juggling

A mathematical language for juggling

We have all seen, at least once in our life, a juggler tossing balls in the air. Why is that so impressing at our eyes?

Despite having just two hands, any respectable juggler can juggle three balls at the same time. Considering for simplicity that one can handle one ball for each hand, how is that possible?

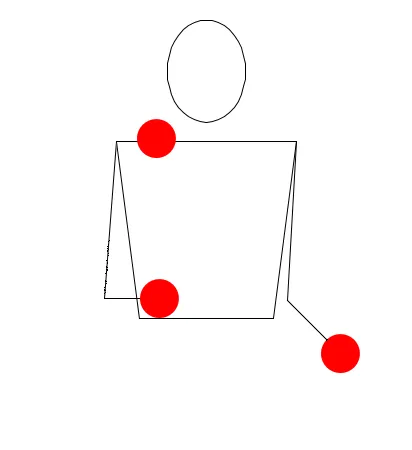

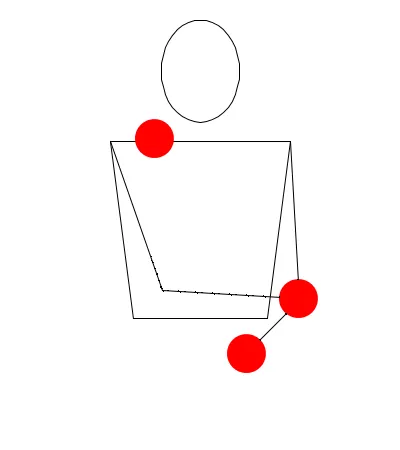

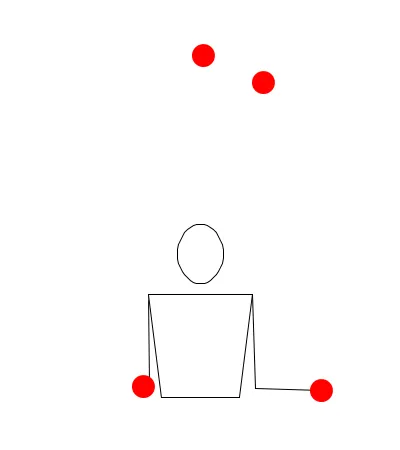

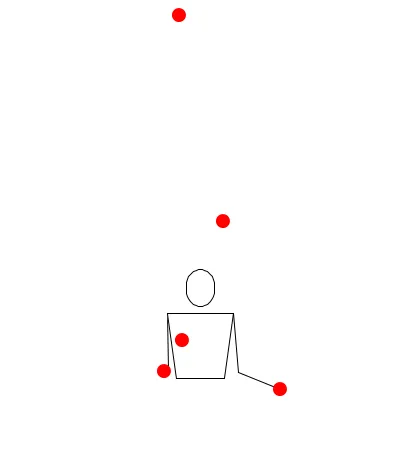

Let's try to analyze Animation 1. We can see that each ball is tossed by one hand to the other: the right hand tosses the balls to the left hand and vice versa. Just as the floating ball floating is about to fall down, the juggler tosses another ball up to free his hand and catch the falling one. Juggling three or more balls is possible only by iterating this principle.

Animation 1: cascade

The pattern represented in Animation 1 is known as three-ball cascade. Let's analyze now Animation 2 and compare it with Animation 1.

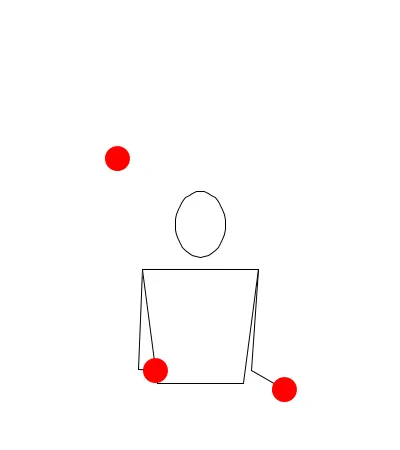

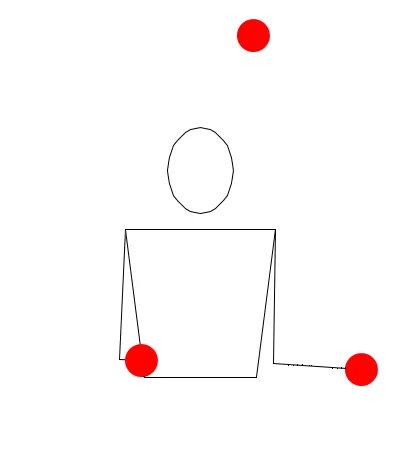

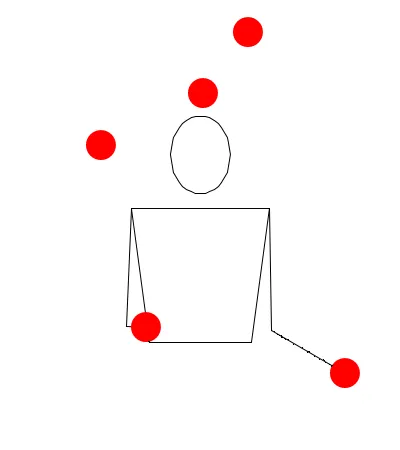

Animation 2

In this case we immediately note that the number of balls is still 3, but the pattern is different. Indeed, by observing it carefully, we see that the juggler tosses the three balls at three different heights.

As you can easily imagine, there is a wide variety of patterns and, if we were to assign a name to each pattern (as in the case of the cascade), we would have to make a prohibitive effort of memory.

For this reason Paul Klimek and Don Hatch, at the beginning of the 80s, independently invented a notation system to describe and name juggling tricks nowadays called siteswap. Afterwards, this system has been developed and extended by other jugglers, like Bruce Tiemann, Jack Boyce and Ben Beever.

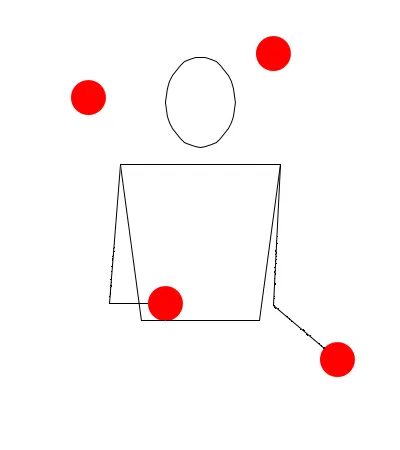

Siteswap is able to describe (and name) all juggling patterns with any number of jugglers and balls, covering both the case of synchronous and asynchronous throws. In the following two animations we can see the same pattern done in both the asynchronous and synchronous versions.

(NOTE: some patterns can be only asynchronous while others can be only synchronous).

Synchronous

Asynchronous

For simplicity, we will describe the so-called Vanilla siteswap. This siteswap notation allows us to describe all the patterns where the balls are tossed asynchronously by a single juggler using both hands.

A limitation of the siteswap notation

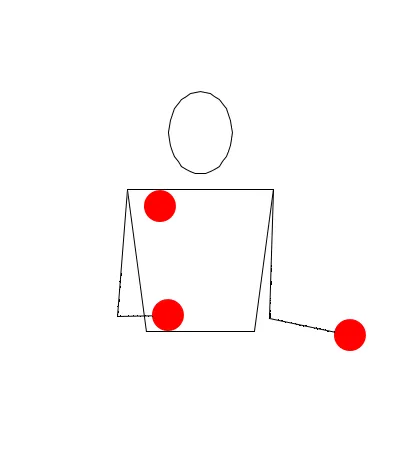

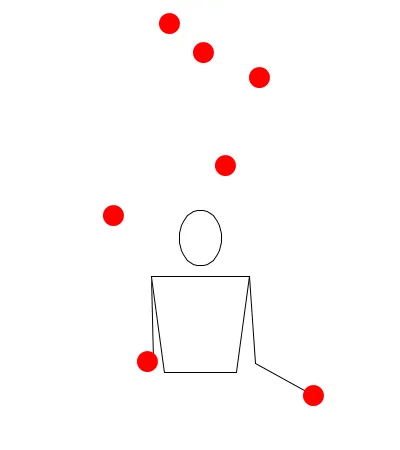

Before going through the description of this notation method, we must underline that siteswap has a limitation. Let's observe the following two animations.

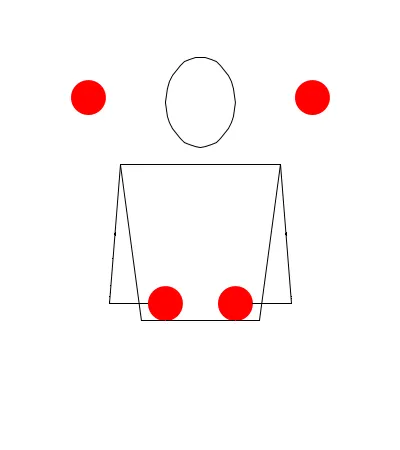

Cascade

Mill's Mess

We have seen already the left-side animation: the three-ball cascade. The right-side pattern, known as three-ball Mill's Mess, is still a cascade but it's done by crossing and switching the hands' position alternatively. Even though the two patterns look very different, they have the same siteswap notation, i.e. they are identical. Indeed, if we focus on the trajectories of the balls with respect to the positions of the hands, we see that Mill's Mess is identical to the normal cascade.

Therefore, siteswap is able to describe juggling patterns by considering the height and the direction in which the balls are tossed (a ball can be tossed to the same or to the other hand) but without considering "how" the pattern is executed.

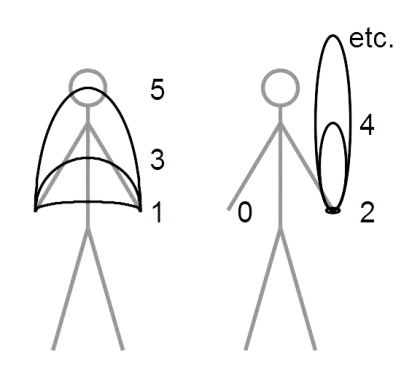

A number for each toss

After this quick introduction, we will now describe how siteswap works. The basic idea is very simple: we assign a positive integer number to each throw that corresponds to the number of beats (soon we will deepen this concept) that the ball takes to complete his trajectory. We use odd numbers (1, 3, 5, ...) for throws from one hand to the other hand and even numbers (2, 4, 6, ...) for throws from one hand to itself. The number zero (0) is used to indicate when one hand is not holding balls during a beat.

In other words:

· A 0 means a beat when the hand is empty.

· A 1 means a direct throw from one hand to the other, during which there is no time to catch or throw other balls, i.e. it is executed in one beat.

· A 2 means a very small throw (almost imperceptible) of a ball to the same hand. While the ball is completing its trajectory, the hand who tossed it has no time to do anything else while the other one has a beat to catch and throw another ball.

· A 3 means a throw from one hand to the other during which both have a beat to juggle a ball each (so there is time to juggle two other balls).

· A 4 means a throw from one hand to the same hand during which the tossing hand can juggle another ball while the other hand can juggle two balls (so there is time to juggle other 3 balls).

· ...

Therefore, the numbers indicate the height at which the balls are tossed relatively to the execution speed of the throws. Indeed, it is possible to toss a 5 with top height under our head if we juggle quickly, or over 3 meters if we juggle slowly. What really matters are the beats left to juggle other balls during the trajectory of the toss. This depends, of course, by the speed of the juggler.

Furthermore, as it is easy to guess from the animations above, the patterns are repeated cyclically. In other words, there is a period after which the pattern is repeated (identically or symmetrically). With the siteswap notation we only write the throws that identify the period of the pattern. For example, the period of 531531531 is 531. We refer to it as 531 by removing the redundant part and without loosing any information.

Once the concepts detailed above are clear, we can try to recognize some patterns:

3

51

423

531

4

71

5

7

753

97531

Not every sequence of numbers is a pattern!

Once we are familiar with the concept of siteswap we can go through a little bit of theory. Let's try to imagine the pattern 432. First, say with the right hand, we toss a 4, i.e. the ball will falls in the same had. Then we toss a 3 with the left hand, i.e. the ball will fall in to the right hand. While the two balls are still completing their trajectory, the right hand executes a 2, in other words it performs a small toss to itself. What will happen is that the right hand will find itself with three balls falling on it at the same time. In siteswap jargon this event is called collision, and the pattern is impossible to repeat. Indeed, the sequence 432 is not executable.

How can we distinguish an executable sequence from a non executable one? Fortunately maths comes to the rescue! Indeed, there is a theorem that characterizes siteswaps and gives us a condition such that there are no collisions.

Characterization theorem of siteswaps

A finite sequence of non-negative numbers s1s2...sns1s2...sn (where nn is the number of digits) is executable if

si+imodn ≠ sj+jmodn,si+imodn ≠ sj+jmodn,

for each i≠ji≠j .

Here, the operator amodbamodb returns the remainder of the division abab

Let's come back to the previous example and verify, using the theorem, that the sequence 432 is not valid:

· 4+1mod3=24+1mod3=2

· 3+2mod3=23+2mod3=2

· 2+3mod3=22+3mod3=2

In this case we get 2 for every digit of the sequence and, according to the theorem, this is not a valid siteswap. We now try to apply the theorem to a valid siteswap that can be obtained by switching the last two digits of the sequence above: 423

· 4+1mod3=24+1mod3=2

· 2+2mod3=12+2mod3=1

· 3+3mod3=03+3mod3=0

It is clear that this siteswap respects the condition imposed by the theorem (and you can actually find it in one of the animations above).

Suppose now to have a valid siteswap, for example 534, How many balls do we need in order to execute it? Again we have another nice and helpful theorem used by the jugglers from all over the world.

Theorem on the number of balls

If s1s2...sns1s2...sn is a valid siteswap (where nn is the number of digits), then we have that

s1+s2...+snn=number of ballss1+s2...+snn=number of balls

Let's try how many balls we need for the 534 pattern:

5+3+43=123=45+3+43=123=4

The answer is 4 balls!