Strength of materials

Strength of materials, also called mechanics of materials, is a subject which deals with the behavior of solid objects subject to stresses and strains. The complete theory began with the consideration of the behavior of one and two dimensional members of structures, whose states of stress can be approximated as two dimensional, and was then generalized to three dimensions to develop a more complete theory of the elastic and plastic behavior of materials. An important founding pioneer in mechanics of materials was Stephen Timoshenko.

The study of strength of materials often refers to various methods of calculating the stresses and strains in structural members, such as beams, columns, and shafts. The methods employed to predict the response of a structure under loading and its susceptibility to various failure modes takes into account the properties of the materials such as its yield strength, ultimate strength, Young's modulus, and Poisson's ratio; in addition the mechanical element's macroscopic properties (geometric properties), such as its length, width, thickness, boundary constraints and abrupt changes in geometry such as holes are considered.

Definition

In mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. The field of strength of materials deals with forces and deformations that result from their acting on a material. A load applied to a mechanical member will induce internal forces within the member called stresses when those forces are expressed on a unit basis. The stresses acting on the material cause deformation of the material in various manners including breaking them completely. Deformation of the material is called strain when those deformations too are placed on a unit basis. The applied loads may be axial (tensile or compressive), or rotational (strength shear). The stresses and strains that develop within a mechanical member must be calculated in order to assess the load capacity of that member. This requires a complete description of the geometry of the member, its constraints, the loads applied to the member and the properties of the material of which the member is composed. With a complete description of the loading and the geometry of the member, the state of stress and state of strain at any point within the member can be calculated. Once the state of stress and strain within the member is known, the strength (load carrying capacity) of that member, its deformations (stiffness qualities), and its stability (ability to maintain its original configuration) can be calculated. The calculated stresses may then be compared to some measure of the strength of the member such as its material yield or ultimate strength. The calculated deflection of the member may be compared to a deflection criteria that is based on the member's use. The calculated buckling load of the member may be compared to the applied load. The calculated stiffness and mass distribution of the member may be used to calculate the member's dynamic response and then compared to the acoustic environment in which it will be used.

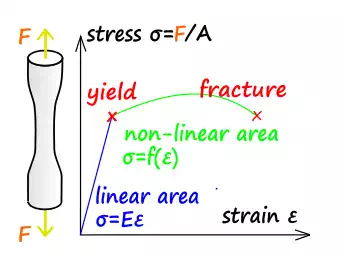

Material strength refers to the point on the engineering stress–strain curve (yield stress) beyond which the material experiences deformations that will not be completely reversed upon removal of the loading and as a result the member will have a permanent deflection. The ultimate strength of the material refers to the maximum value of stress reached. The fracture strength is the stress value at fracture (the last stress value recorded).

Types of loadings

· Transverse loadings — Forces applied perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of a member. Transverse loading causes the member to bend and deflect from its original position, with internal tensile and compressive strains accompanying the change in curvature of the member.[1] Transverse loading also induces shear forces that cause shear deformation of the material and increase the transverse deflection of the member.

· Axial loading — The applied forces are collinear with the longitudinal axis of the member. The forces cause the member to either stretch or shorten.[2]

· Torsional loading — Twisting action caused by a pair of externally applied equal and oppositely directed force couples acting on parallel planes or by a single external couple applied to a member that has one end fixed against rotation.

Stress terms

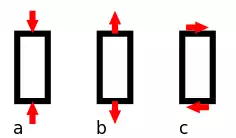

A material being loaded in a) compression, b) tension, c) shear.

Uniaxial stress is expressed by

![]()

where F is the force [N] acting on an area A [m2]. The area can be the undeformed area or the deformed area, depending on whether engineering stress or true stress is of interest.

Compressive stress (or compression) is the stress state caused by an applied load that acts to reduce the length of the material (compression member) along the axis of the applied load, it is in other words a stress state that causes a squeezing of the material. A simple case of compression is the uniaxial compression induced by the action of opposite, pushing forces. Compressive strength for materials is generally higher than their tensile strength. However, structures loaded in compression are subject to additional failure modes, such as buckling, that are dependent on the member's geometry.

Tensile stress is the stress state caused by an applied load that tends to elongate the material along the axis of the applied load, in other words the stress caused by pulling the material. The strength of structures of equal cross sectional area loaded in tension is independent of shape of the cross section. Materials loaded in tension are susceptible to stress concentrations such as material defects or abrupt changes in geometry. However, materials exhibiting ductile behavior (most metals for example) can tolerate some defects while brittle materials (such as ceramics) can fail well below their ultimate material strength.

Shear stress is the stress state caused by the combined energy of a pair of opposing forces acting along parallel lines of action through the material, in other words the stress caused by faces of the material sliding relative to one another. An example is cutting paper with scissor or stresses due to torsional loading.

Strength terms

Mechanical properties of materials include the yield strength, tensile strength, fatigue strength, crack resistance, and other characteristics.

· Yield strength is the lowest stress that produces a permanent deformation in a material. In some materials, like aluminium alloys, the point of yielding is difficult to identify, thus it is usually defined as the stress required to cause 0.2% plastic strain. This is called a 0.2% proof stress.

· Compressive strength is a limit state of compressive stress that leads to failure in a material in the manner of ductile failure (infinite theoretical yield) or brittle failure (rupture as the result of crack propagation, or sliding along a weak plane — see shear strength).

· Tensile strength or ultimate tensile strength is a limit state of tensile stress that leads to tensile failure in the manner of ductile failure (yield as the first stage of that failure, some hardening in the second stage and breakage after a possible "neck" formation) or brittle failure (sudden breaking in two or more pieces at a low stress state). Tensile strength can be quoted as either true stress or engineering stress, but engineering stress is the most commonly used.

·

Fatigue

strength is a measure of the strength of a material or a component under

cyclic loading,[7] and is usually more difficult to assess than the static

strength measures. Fatigue strength is quoted as stress amplitude or stress

range![]() usually

at zero mean stress, along with the number of cycles to failure under that

condition of stress.

usually

at zero mean stress, along with the number of cycles to failure under that

condition of stress.

· Impact strength is the capability of the material to withstand a suddenly applied load and is expressed in terms of energy. Often measured with the Izod impact strength test or Charpy impact test, both of which measure the impact energy required to fracture a sample. Volume, modulus of elasticity, distribution of forces, and yield strength affect the impact strength of a material. In order for a material or object to have a high impact strength the stresses must be distributed evenly throughout the object. It also must have a large volume with a low modulus of elasticity and a high material yield strength.

Strain (deformation) terms

· Deformation of the material is the change in geometry created when stress is applied (as a result of applied forces, gravitational fields, accelerations, thermal expansion, etc.). Deformation is expressed by the displacement field of the material.

· Strain or reduced deformation is a mathematical term that expresses the trend of the deformation change among the material field. Strain is the deformation per unit length. In the case of uniaxial loading the displacements of a specimen (for example a bar element) lead to a calculation of strain expressed as the quotient of the displacement and the original length of the specimen. For 3D displacement fields it is expressed as derivatives of displacement functions in terms of a second order tensor (with 6 independent elements).

· Deflection is a term to describe the magnitude to which a structural element is displaced when subject to an applied load.

Stress–strain relations

Basic static response of a specimen under tension

· Elasticity is the ability of a material to return to its previous shape after stress is released. In many materials, the relation between applied stress is directly proportional to the resulting strain (up to a certain limit), and a graph representing those two quantities is a straight line.

The slope of this line is known as Young's modulus, or the "modulus of elasticity." The modulus of elasticity can be used to determine the stress–strain relationship in the linear-elastic portion of the stress–strain curve. The linear-elastic region is either below the yield point, or if a yield point is not easily identified on the stress–strain plot it is defined to be between 0 and 0.2% strain, and is defined as the region of strain in which no yielding (permanent deformation) occurs.

· Plasticity or plastic deformation is the opposite of elastic deformation and is defined as unrecoverable strain. Plastic deformation is retained after the release of the applied stress. Most materials in the linear-elastic category are usually capable of plastic deformation. Brittle materials, like ceramics, do not experience any plastic deformation and will fracture under relatively low strain, while ductile materials such as metallics, lead, or polymers will plasticly deform much more before a fracture initiation.

Consider the difference between a carrot and chewed bubble gum. The carrot will stretch very little before breaking. The chewed bubble gum, on the other hand, will plastically deform enormously before finally breaking.