Intrinsic motion

In Newtonian mechanics, one customarily uses all three Cartesian coordinates, or other 3D coordinate system, to refer to a body's position during its motion. In physical systems, however, some structure or other system usually constrains the body's motion from taking certain directions and pathways. So a full set of Cartesian coordinates is often unneeded, as the constraints determine the evolving relations among the coordinates, which relations can be modeled by equations corresponding to the constraints. In the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian formalisms, the constraints are incorporated into the motion's geometry, reducing the number of coordinates to the minimum needed to model the motion. These are known as generalized coordinates, denoted qi (i = 1, 2, 3...).

Difference between curvillinear and generalized coordinates

Generalized coordinates incorporate constraints on the system. There is one generalized coordinate qi for each degree of freedom (for convenience labelled by an index i = 1, 2...N), i.e. each way the system can change its configuration; as curvilinear lengths or angles of rotation. Generalized coordinates are not the same as curvilinear coordinates. The number of curvilinear coordinates equals the dimension of the position space in question (usually 3 for 3d space), while the number of generalized coordinates is not necessarily equal to this dimension; constraints can reduce the number of degrees of freedom (hence the number of generalized coordinates required to define the configuration of the system), following the general rule:

[dimension of position space (usually 3)] × [number of constituents of system ("particles")] − (number of constraints)

= (number of degrees of freedom) = (number of generalized coordinates)

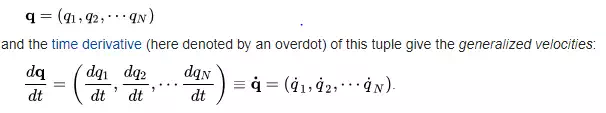

For a system with N degrees of freedom, the generalized coordinates can be collected into an N-tuple:

and the time derivative (here denoted by an overdot) of this tuple give the generalized velocities:

D'Alembert's principle

The foundation which the subject is built on is D'Alembert's principle.

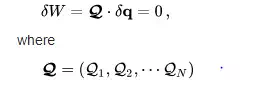

This principle states that infinitesimal virtual work done by a force across reversible displacements is zero, which is the work done by a force consistent with ideal constraints of the system. The idea of a constraint is useful - since this limits what the system can do, and can provide steps to solving for the motion of the system. The equation for D'Alembert's principle is:

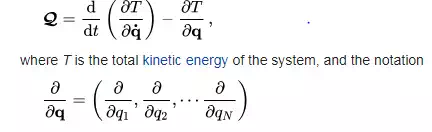

are the generalized forces (script Q instead of ordinary Q is used here to prevent conflict with canonical transformations below) and q are the generalized coordinates. This leads to the generalized form of Newton's laws in the language of analytical mechanics:

is a useful shorthand (see matrix calculus for this notation).

Holonomic constraints

If the curvilinear coordinate system is defined by the standard position vector r, and if the position vector can be written in terms of the generalized coordinates q and time t in the form:

![]()

and this relation holds for all times t, then q are called Holonomic constraints.[4] Vector r is explicitly dependent on t in cases when the constraints vary with time, not just because of q(t). For time-independent situations, the constraints are also called scleronomic, for time-dependent cases they are called rheonomic.

Lagrangian mechanics

Lagrangian and Euler–Lagrange equations

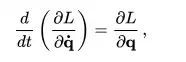

The introduction of generalized coordinates and the fundamental Lagrangian function:

![]()

where T is the total kinetic energy and V is the total potential energy of the entire system, then either following the calculus of variations or using the above formula - lead to the Euler–Lagrange equations;

which are a set of N second-order ordinary differential equations, one for each qi(t).

This formulation identifies the actual path followed by the motion as a selection of the path over which the time integral of kinetic energy is least, assuming the total energy to be fixed, and imposing no conditions on the time of transit.

Configuration space

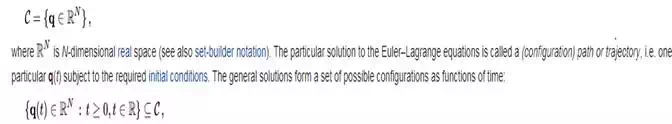

The Lagrangian formulation uses the configuration space of the system, the set of all possible generalized coordinates:

The configuration space can be defined more generally, and indeed more deeply, in terms of topological manifolds and the tangent bundle.