Propfan

A propfan or open rotor engine is a type of aircraft engine related in concept to both the turboprop and turbofan, but distinct from both. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) defines it as "A turbine engine featuring contra rotating fan stages not enclosed within a casing." The engine uses a gas turbine to drive an unshrouded (open) contra-rotating propeller like a turboprop, but the design of the propeller itself is more tightly coupled to the turbine design and the two are certified as a single unit.

NASA / GE unducted fan

A propfan is typically designed with a large number of short, highly twisted blades, similar to a turbofan's bypass compressor (the "fan" itself). For this reason, the propfan has been variously described as an "unducted fan" or an "ultra-high-bypass (UHB) turbofan". In technical papers it is described as "a small diameter, highly loaded multiple bladed variable pitch propulsor having swept blades with thin advanced airfoil sections, integrated with a nacelle contoured to retard the airflow through the blades thereby reducing compressibility losses and designed to operate with a turbine engine and using a single stage reduction gear resulting in high performance."

The design is

intended to offer the speed and performance of a turbofan, with the fuel

economy of a turboprop. The propfan concept was first revealed by Carl Rohrbach and Bruce Metzger of the Hamilton Standard Division of United

Technologies in 1975 and was patented by Robert Cornell and Carl Rohrbach of Hamilton Standard in 1979. Later work by

General Electric on similar propulsors was

done under the name unducted fan,

which was a modified turbofan engine, with the fan

placed outside the engine

nacelle on

the same axis as the compressor blades.

Limitations and solutions

Propeller blade tip speed limit

Turboprops have

an optimum speed below about 450 mph (700 km/h). The reason is that all propellers lose efficiency at high speed, due to an

effect known as wave

drag that

occurs just below supersonic speeds. This powerful

form of drag has a sudden onset,

and led to the concept of a sound

barrier when

it was first encountered in the 1940s. In the case of a propeller, this effect

can happen any time the propeller is spun fast enough that the blade tips

approach the speed of sound, even if the aircraft is motionless on the ground.

The most

effective way to counteract this problem (to some degree) is by adding more

blades to the propeller, allowing it to deliver more power at a lower

rotational speed. This is why many World

War II fighter

designs started with two or three-blade propellers and by the end of the war

were using up to five blades in some cases as the engines were upgraded and new

propellers were needed to more efficiently convert that power. The major

downside to this approach is that adding blades makes the propeller harder to

balance and maintain and the additional blades cause minor performance

penalties (due to drag and efficiency issues). But even with these sorts of

measures at some point the forward speed of the plane combined with the

rotational speed of the propeller will once again result in wave drag problems.

For most aircraft this will occur at speeds over about 450 mph (700 km/h).

Swept

propeller

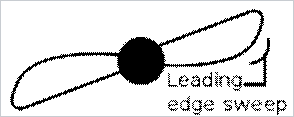

A method of

decreasing wave drag was discovered by German researchers in 1935—sweeping the

wing backwards. Today, almost all aircraft designed to fly much above 450 mph

(700 km/h) use a swept

wing. In the

1970s, Hamilton

Standard started

researching propellers

with similar sweep.

Since the inside of the propeller is moving slower than the outside, the blade

is progressively more swept toward the outside, leading to a curved shape

similar to a scimitar - a practice that was

first used as far back as 1909, in the Chauvière make

of a two-bladed wood propeller used on the Blériot XI.

Jet aircraft fuel economy

Jet aircraft fly

faster than conventional propeller-driven aircraft. However, they use more

fuel, so that for the same fuel consumption a propeller installation produces

more thrust. As fuel costs become an increasingly important aspect of

commercial aviation, engine designers continue to seek ways to improve aero

engine efficiency.

The propfan concept was developed to deliver 35% better fuel efficiency than contemporary turbofans. In static and air tests on a modified Douglas DC-9, propfans reached a 30% improvement over the OEM turbofans. This efficiency came at a price, as one of the major problems with the propfan is noise, particularly in an era where aircraft are required to comply with increasingly strict aircraft noise regulations. However, in 2012 GE expected that propfans could meet these noise levels by 2030, when new narrowbody generations from Boeing and Airbus become available. Airlines consistently ask for low noise, and then maximum fuel efficiency.

The Hamilton Standard Division of United Technologies developed the propfan concept in the early 1970s. Numerous design variations of the propfan were tested by Hamilton Standard, in conjunction with NASA in this decade. This testing led to the Propfan Test Assessment (PTA) program, where Lockheed-Georgia proposed modifying a Gulfstream II to act as in-flight testbed for the propfan concept and McDonnell Douglas proposed modifying a DC-9 for the same purpose. NASA chose the Lockheed proposal, where the aircraft had a nacelle added to the left wing, containing a 6000 hp Allison 570 turboprop engine (derived from the XT701 turboshaft developed for the Boeing Vertol XCH-62 program), powering a 9-foot diameter Hamilton Standard SR-7 propfan. The aircraft, so configured, first flew in March 1987. After an extensive test program, the modifications were removed from the aircraft.

General Electric's GE36 Unducted Fan was a variation on the original propfan concept, and appears similar to a pusher configuration piston engine. GE's UDF had a novel direct-drive arrangement, where the reduction gearbox was replaced by a low-speed seven-stage free turbine. One set of turbine rotors drove the forward set of propellers, while the rear set was driven by the other set of rotors which rotated in the opposite direction. The turbine had 14 blade rows with seven stages. Each stage was a pair of contra-rotating rows. Boeing intended to offer GE's pusher UDF engine on the 7J7 platform, and McDonnell Douglas was going to do likewise on their MD-94X airliner. The GE36 was first flight tested mounted on the #3 engine station of a Boeing 727-100 in 1986.

McDonnell

Douglas developed a proof-of-concept aircraft by modifying its company-owned

MD-80. They removed the JT8D turbofan engine from the left side of the fuselage

and replaced it with the GE36. A number of test flights were conducted,

initially out of Mojave, California, which proved the airworthiness,

aerodynamic characteristics, and noise signature of the design. Following the

initial tests, a first-class cabin was installed inside the aft fuselage and

airline executives were offered the opportunity to experience the UDF-powered

aircraft first-hand. The test and marketing flights of the GE-outfitted

demonstrator aircraft concluded in 1988, exhibiting a 30% reduction in fuel consumption

over turbo-fan powered MD-80, full Stage III noise compliance, and low levels

of interior noise/vibration. Due to jet fuel price drops and shifting marketing

priorities, Douglas shelved the program the following year.

In the 1980s, Allison collaborated with Pratt & Whitney on demonstrating the 578-DX propfan. Unlike the competing GE36 UDF, the 578-DX was fairly conventional, having a reduction gearbox between the LP turbine and the propfan blades. The 578-DX was successfully flight tested on a McDonnell Douglas MD-80. However, none of the above projects came to fruition, mainly because of excessive cabin noise (compared to turbofans) and low fuel prices.

Progress D27 Propfans fitted to an Antonov An-70

The Progress D-27 propfan,

developed in the U.S.S.R., was designed with the propfan blades

at the front of the engine in a tractor configuration. Two rear-mounted

D-27 propfans propelled the Ukrainian Antonov An-180, which was scheduled for a

1995 entry into service. Another propfan application

was the Russian Yakovlev Yak-46. During the 1990s, Antonov also developed

the An-70, powered by four Progress

D-27s in a tractor

configuration;

the Russian Air Force placed an order for

164 aircraft in 2003, which was

subsequently canceled. However, the An-70

remains available for further investment and production.

With increasing prices for jet fuel and the emphasis on engine/airframe efficiency to reduce emissions, there is renewed interest in the propfan concept for jetliners that might come into service beyond the Boeing 787 and Airbus A350XWB. For instance, Airbus has patented aircraft designs with twin rear-mounted contra-rotating propfans.