Temperature Measuring Instruments

The temperature of numerous items must be known for an aircraft to be operated properly. Engine oil, carburetor mixture, inlet air, free air, engine cylinder heads, heater ducts, and exhaust gas temperature of turbine engines are all items requiring temperature monitoring. Many other temperatures must also be known. Different types of thermometers are used to collect and present temperature information.

Non-Electric Temperature Indicators

The physical characteristics of most materials change when exposed to changes in temperature. The changes are consistent, such as the expansion or contraction of solids, liquids, and gases. The coefficient of expansion of different materials varies and it is unique to each material. Most everyone is familiar with the liquid mercury thermometer. As the temperature of the mercury increases, it expands up a narrow passage that has a graduated scale upon it to read the temperature associated with that expansion. The mercury thermometer has no application in aviation.

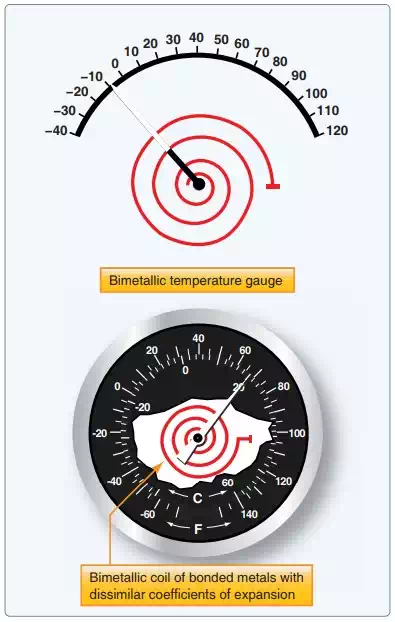

A bimetallic thermometer is very useful in aviation. The temperature sensing element of a bimetallic thermometer is made of two dissimilar metals strips bonded together. Each metal expands and contracts at a different rate when temperature changes. One end of the bimetallic strip is fixed, the other end is coiled. A pointer is attached to the coiled end which is set in the instrument housing. When the bimetallic strip is heated, the two metals expand. Since their expansion rates differ and they are attached to each other, the effect is that the coiled end tries to uncoil as the one metal expands faster than the other. This moves the pointer across the dial face of the instrument. When the temperature drops, the metals contract at different rates, which tends to tighten the coil and move the pointer in the opposite direction.

Direct reading bimetallic temperature gauges are often used in light aircraft to measure free air temperature or outside air temperature (OAT). In this application, a collecting probe protrudes through the windshield of the aircraft to be exposed to the atmospheric air. The coiled end of the bimetallic strip in the instrument head is just inside the windshield where it can be read by the pilot.

A bimetallic temperature gauge works because of the dissimilar coefficients of expansion of two metals bonded together. When bent into a coil, cooling or heating causes the dissimilar metal coil to tighten, or unwind, moving the pointer across the temperature scale on the instrument dial face.

A bourdon tube is also used as a direct reading non-electric temperature gauge in simple, light aircraft. By calibrating the dial face of a bourdon tube gauge with a temperature scale, it can indicate temperature. The basis for operation is the consistent expansion of the vapor produced by a volatile liquid in an enclosed area. This vapor pressure changes directly with temperature. By filling a sensing bulb with such a volatile liquid and connecting it to a bourdon tube, the tube causes an indication of the rising and falling vapor pressure due to temperature change. Calibration of the dial face in degrees Fahrenheit or Celsius, rather than psi, provides a temperature reading. In this type of gauge, the sensing bulb is placed in the area needing to have temperature measured. A long capillary tube connects the bulb to the bourdon tube in the instrument housing. The narrow diameter of the capillary tube ensures that the volatile liquid is lightweight and stays primarily in the sensor bulb. Oil temperature is sometimes measured this way.