Supersonic Aerodynamics: Designing Rocket Nozzles

One of the most basic equations in fluid dynamics is Bernoulli’s

equation: the relationship between pressure and velocity in a moving fluid. It

is so fundamental to aerodynamics that it is often cited (incorrectly!) when

explaining how aircraft wings create lift. The fact is that Bernoulli’s

equation is not a fundamental equation of aerodynamics at all, but a particular

case of the conservation of energy applied to a fluid of constant density.

The underlying assumption of constant density is only valid for

low-speed flows, but does not hold in the case of high-speed flows where the

kinetic energy causes changes in the gas’ density. As the speed of a fluid

approaches the speed of sound, the properties of the fluid undergo changes that

cannot be modelled accurately using Bernoulli’s equation. This type of flow is

known as compressible. As a rule of thumb, the demarcation line for

compressibility is around 30% the speed of sound, or around 100 m/s for dry air

close to Earth’s surface. This means that air flowing over a normal passenger

car can be treated as incompressible, whereas the flow over a modern jumbo jet

is not.

The fluid dynamics and thermodynamics of compressible flow are described

by five fundamental equations, of which Bernoulli’s equation is a special case

under the conditions of constant density. For example, let’s consider an

arbitrary control volume of fluid and assume that any flow of this fluid is

● adiabatic, meaning there is no heat

transfer out of or into the control volume.

● inviscid, meaning no friction is

present.

● at constant energy, meaning no external

work (for example by a compressor) is done on the fluid.

This type of flow is known as isentropic (constant entropy), and

includes fluid flow over aircraft wings, but not fluid flowing through rotating

turbines.

At this point you might be wondering how we can possible increase the

speed of a gas without passing it through some machine that adds energy to

the flow?

The answer is the fundamental law of conservation of energy. The

temperature, pressure and density of a fluid at rest are known as the

stagnation temperature, stagnation pressure and stagnation density,

respectively. These stagnation values are the highest values that the gas can

possibly attain. As the flow velocity of a gas increases, the pressure,

temperature and density must fall in order to conserve energy, i.e. some of the

internal energy of the gas is converted into kinetic energy. Hence, expansion

of a gas leads to an increase in its velocity.

The isentropic flow described above is governed by five fundamental

conservation equations that are expressed in terms density (![]() ), pressure (

), pressure (![]() ),

velocity (

),

velocity (![]() ), area

(

), area

(![]() ), mass flow rate (

), mass flow rate (![]() ), temperature (

), temperature (![]() ) and entropy (

) and entropy (![]() ). This

means that at two stations of the flow, 1 and 2, the following expressions must

hold:

). This

means that at two stations of the flow, 1 and 2, the following expressions must

hold:

– Conservation of mass: ![]()

– Conservation of linear momentum: ![]()

– Conservation of energy: ![]()

– Equation of state: ![]()

– Conservation of entropy (in adiabatic and inviscid flow only): ![]()

where ![]() is

the specific universal gas constant (normalised by molar mass) and

is

the specific universal gas constant (normalised by molar mass) and ![]() is the specific heat at constant

pressure.

is the specific heat at constant

pressure.

The Speed of Sound

Fundamental to the analysis of supersonic flow is the concept of

the speed of sound. Without knowledge of the local speed of sound

we cannot gauge where we are on the compressibility spectrum.

As a simple mind experiment, consider the plunger in a plastic syringe.

The speed of sound describes the speed at which a pressure wave is transmitted

through the air chamber by a small movement of the piston. As a very weak wave

is being transmitted, the assumptions made above regarding no heat transfer and

inviscid flow are valid here, and any variations in the temperature and

pressure are small. Under these conditions it can be shown from only the five

conservation equations above that the local speed of sound within the fluid is

given by:

![]()

The term ![]() is

the heat capacity ratio, i.e. the ratio of the specific heat at constant

pressure (

is

the heat capacity ratio, i.e. the ratio of the specific heat at constant

pressure (![]() ) and

specific heat at constant volume (

) and

specific heat at constant volume (![]() ), and

is independent of temperature and pressure. The specific universal gas constant

), and

is independent of temperature and pressure. The specific universal gas constant ![]() , as

the name suggests, is also a constant and is given by the difference of the

specific heats,

, as

the name suggests, is also a constant and is given by the difference of the

specific heats, ![]() . As the above equation

shows, the speed of sound of a gas only depends on the temperature. The speed

of sound in dry air (

. As the above equation

shows, the speed of sound of a gas only depends on the temperature. The speed

of sound in dry air (![]() J/(kg K),

J/(kg K), ![]() =

1.4) at the freezing point of 0° C (273 Kelvin) is 331 m/s.

=

1.4) at the freezing point of 0° C (273 Kelvin) is 331 m/s.

Why is the speed of sound purely a function of temperature?

Well, the temperature of a gas is a measure of the gas’ kinetic energy,

which essentially describes how much the individual gas molecules are jiggling

about. As the air molecules are moving randomly with differing instantaneous

speeds and energies at different points in time, the temperature describes the

average kinetic energy of the collection of molecules over a period of time.

The higher the temperature the more ferocious the molecules are jiggling about

and the more often they bump into each other. A pressure wave momentarily

disturbs some particles and this extra energy is transferred through the gas by

the collisions of molecules with their neighbours. The higher the temperature,

the quicker the pressure wave is propagated through the gas due to the higher

rate of collisions.

This visualisation is also helpful in explaining why the speed of sound

is a special property in fluid dynamics. One possible source of an externally

induced pressure wave is the disturbance of an object moving through the fluid.

As the object slices through the air it collides with stationary air particles

upstream of the direction of motion. This collision induces a pressure wave

which is transmitted via the molecular collisions described above. Now imagine

what happens when the object is travelling faster than the speed of sound. This

means the moving object is creating new disturbances upstream of its direction

of motion at a faster rate than the air can propagate the pressure waves

through the gas by means of molecular collisions. The rate of pressure wave

creation is faster than the rate of pressure wave transmission. Or put more

simply, information is created more quickly than it can be transmitted; we have

run out of bandwidth. For this reason, the speed of sound marks an important

demarcation line in fluid dynamics which, if exceeded, introduces a number of

counter-intuitive effects.

Given the importance of the speed of sound, the relative speed of a body

with respect to the local speed of sound is described by the Mach Number:

![]()

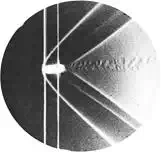

The Mach number is named after Ernst Mach who conducted many of the

first experiments on supersonic flow and captured the first ever photograph of

a shock wave (shown below).

As described previously, when an object moves through a gas, the

molecules just ahead of the object are pushed out of the way, creating a

pressure pulse that propagates in all directions (imagine a spherical pressure

wave) at the speed of sound relative to the fluid. Now let’s imagine a

loudspeaker emitting three sound pulses at equal intervals, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.

If the object is stationary, then the three sound pulses at times ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are concentric (see figure below).

are concentric (see figure below).

However, if the object starts moving in one direction, the centre of the

spheres shift to the side and the sound pulses bunch up in the direction of

motion and spread out in the opposite direction. A bystander listening to the

sound pulses upstream of the loudspeaker would therefore hear a higher pitched

sound than a downstream bystander as the frequency the sound waves reaching him

are higher. This is known as the Doppler effect.

If the object now accelerates to the local speed of sound, then the

centres of the sound pulse spheres will be travelling just as fast as the sound

waves themselves and the spherical waves all touch at one point. This means no

sound can travel ahead of the loudspeaker and consequently an observer ahead of

the loudspeaker will hear nothing.

Finally, if the loudspeaker travels at a uniform speed greater than the

speed of sound, then the loudspeaker will in fact overtake the sound pulses it

is creating. In this case, the loudspeaker and the leading edges of the sound

waves form a locus known as the Mach cone. An observer standing outside this

cone is in a zone of silence and is not aware of the sound waves created by the

loudspeaker.

S is the starting point of

the load speaker which then moves to the right of the screen emitting three

sound pulses at times dt, 2dt and 3dt.

The half angle of this cone is known as the Mach angle and is equal to

![]()

and therefore ![]() when

the object is travelling at the speed of sound and

when

the object is travelling at the speed of sound and ![]() decreases with increasing velocity.

decreases with increasing velocity.

As mentioned previously, the temperature, pressure and density of the

gas all fall as the flow speed of the gas increases. The relation between Mach

number and temperature can be derived directly from the conservation of energy

(stated above) and is given by:

![]()

where ![]() is

the maximum total temperature, also known as stagnation temperature, and

is

the maximum total temperature, also known as stagnation temperature, and ![]() is called the static temperature of the gas moving at

velocity

is called the static temperature of the gas moving at

velocity ![]() .

.

An intuitive way of explaining the relationship between temperature and

flow speed is to return to the description of the vibrating gas molecules. Previously

we established that the temperature of a gas is a measure of the kinetic energy

of the vibrating molecules. Hence, the stagnation temperature is the kinetic

energy of the random motion of the air molecules in a stationary gas. However,

if the gas is moving in a certain direction at speed then there will be a real

net movement of the air molecules. The molecules will still be vibrating about,

but at a net movement in a specific direction. If the total energy of the gas

is to remain constant (no external work), some of the kinetic energy of the

random vibrations must be converted into kinetic energy of directed motion, and

hence the energy associated with random vibration, i.e. the temperature, must

fall. Therefore, the gas temperature falls as some of the thermal internal

energy is converted into kinetic energy.

In a similar fashion, for flow at constant entropy, both the pressure

and density of the fluid can be quantified by the Mach number.

![]()

![]()

In this regard the Mach number can simply be interpreted as the degree

of compressibility of a gas. For small Mach numbers (M< 0.3), the density

changes by less than 5% and this is why the assumptions of constant density

underlying Bernoulli’s equation are applicable.

An Application: Convergent-divergent Nozzles

In typical engineering applications, compressible flow typically occurs

in ducts, e.g. engine intakes, or through the exhaust nozzles of afterburners

and rockets. This latter type of flow typically features changes in area. If we

consider a differential, i.e. infinitesimally small control volume, where the

cross-sectional area changes by ![]() , then the velocity of the flow must also

change by a small amount

, then the velocity of the flow must also

change by a small amount ![]() in

order to conserve the mass flow rate. Under these conditions we can show that

the change in velocity is related to the change in area by the following

equation:

in

order to conserve the mass flow rate. Under these conditions we can show that

the change in velocity is related to the change in area by the following

equation:

![]()

Without solving this equation for a specific problem we can reveal some

interesting properties of compressible flow:

● For M

< 1, i.e. subsonic flow, ![]() with

with ![]() a

positive constant. This means that increasing the flow velocity is only possible

with a decrease in cross-sectional area and vice versa.

a

positive constant. This means that increasing the flow velocity is only possible

with a decrease in cross-sectional area and vice versa.

● For M =

1, i.e. sonic flow ![]() .

As

.

As ![]() has

to be finite this implies that

has

to be finite this implies that ![]() and therefore the area

must be a minimum for sonic flow.

and therefore the area

must be a minimum for sonic flow.

● For M

> 1, i.e. supersonic flow ![]() . This

means that increasing the flow velocity is only possible with an increase in

cross-sectional area and vice versa.

. This

means that increasing the flow velocity is only possible with an increase in

cross-sectional area and vice versa.

Subsonic and supersonic flow in nozzles

Hence, because of the term ![]() , changes in subsonic and

supersonic flows are of opposite sign. This means that if we want to expand a

gas from subsonic to supersonic speeds, we must first pass the flow through a

convergent nozzle to reach Mach 1, and then expand it in a divergent nozzle to

reach supersonic speeds. Therefore, at the point of minimum area, known as the

throat, the flow must be sonic and, as a result, rocket engines always have

large bell-shaped nozzle in order to expand the exhaust gases into supersonic

jets.

, changes in subsonic and

supersonic flows are of opposite sign. This means that if we want to expand a

gas from subsonic to supersonic speeds, we must first pass the flow through a

convergent nozzle to reach Mach 1, and then expand it in a divergent nozzle to

reach supersonic speeds. Therefore, at the point of minimum area, known as the

throat, the flow must be sonic and, as a result, rocket engines always have

large bell-shaped nozzle in order to expand the exhaust gases into supersonic

jets.

The flow through such a bell-shaped convergent-divergent nozzle is

driven by the pressure difference between the combustion chamber and the nozzle

outlet. In the combustion chamber the gas is basically at rest and therefore at

stagnation pressure. As it exits the nozzle, the gas is typically moving and

therefore at a lower pressure. In order to create supersonic flow, the first

important condition is a high enough pressure ratio between the combustion

chamber and the throat of the nozzle to guarantee that the flow is sonic at the

throat. Without this critical condition at the throat, there can be no

supersonic flow in the divergent section of the nozzle.

We can determine this exact pressure ratio for dry air (![]() ) from the relationship

between pressure and Mach number given above:

) from the relationship

between pressure and Mach number given above:

![]()

Therefore, a pressure ratio greater than or equal to 1.893 is required

to guarantee sonic flow at the throat. The temperature at this condition would

then be:

![]()

or 1.2 times smaller than the

temperature in the combustion chamber (as long as there is no heat loss or work

done in the meantime, i.e. isentropic flow).

Shock Waves

The term “shock wave” implies a certain sense of drama; the state of

shock after a traumatic event, the shock waves of a revolution, the shock waves

of an earthquake, thunder, the cracking of a whip, and so on. In aerodynamics,

a shock wave describes a thin front of energy, approximately ![]() m in thickness (that’s

0.1 microns, or 0.0001 mm) across which the state of the gas changes abruptly.

The gas density, temperature and pressure all significantly increase across the

shock wave. A specific type of shock wave that lends itself nicely to

straightforward analysis is called a normal shock wave, as it forms at right

angles to the direction of motion. The conservation laws stated at the beginning

of this post still hold and these can be used to prove a number of interesting

relations that are known as the Prandtl relation

and the Rankine equations.

m in thickness (that’s

0.1 microns, or 0.0001 mm) across which the state of the gas changes abruptly.

The gas density, temperature and pressure all significantly increase across the

shock wave. A specific type of shock wave that lends itself nicely to

straightforward analysis is called a normal shock wave, as it forms at right

angles to the direction of motion. The conservation laws stated at the beginning

of this post still hold and these can be used to prove a number of interesting

relations that are known as the Prandtl relation

and the Rankine equations.

The Prandtl relation provides a

means of calculating the speed of the fluid flow after a normal shock, given

the flow speed before the shock.

![]()

where ![]() is

the speed of sound at the stagnation temperature of the flow. Because we are

assuming no external work or heat transfer across the shock wave, the internal

energy of the flow must be conserved across the shock, and therefore the

stagnation temperature also does not change across the shock wave. This means

that the speed of sound at the stagnation temperature

is

the speed of sound at the stagnation temperature of the flow. Because we are

assuming no external work or heat transfer across the shock wave, the internal

energy of the flow must be conserved across the shock, and therefore the

stagnation temperature also does not change across the shock wave. This means

that the speed of sound at the stagnation temperature ![]() must also be conserved and therefore

the Prandtl relation shows that the product

of upstream and downstream velocities must always be a constant. Hence, they

are inversely proportional.

must also be conserved and therefore

the Prandtl relation shows that the product

of upstream and downstream velocities must always be a constant. Hence, they

are inversely proportional.

We can further extend the Prandtl relation

to express all flow properties (speed, temperature, pressure and density) in

terms of the upstream Mach number ![]() , and hence the degree of compressibility

before the shock wave. In the Prandtl relation

we replace the velocities with their Mach numbers and divide both sides of the

equations by

, and hence the degree of compressibility

before the shock wave. In the Prandtl relation

we replace the velocities with their Mach numbers and divide both sides of the

equations by ![]()

![]()

and because we know the relationship

between temperature, stagnation temperature and Mach number from above:

![]()

substitution for states 1 and 2

the Prandtl relation is transformed into:

![]()

This equation looks a bit clumsy but it is actually quite

straightforward given that the terms involving ![]() are constants. For

clarity a graphical representation of the the equation

is shown below.

are constants. For

clarity a graphical representation of the the equation

is shown below.

Change in Mach number across a shock wave

It is clear from the figure that for ![]() we necessarily have

we necessarily have ![]() .

Therefore a shock wave automatically turns the flow from supersonic to

subsonic. In the case of

.

Therefore a shock wave automatically turns the flow from supersonic to

subsonic. In the case of ![]() we

have reached the limiting case of a sound wave for which there is no change in

the gas properties. Similar expressions can also be derived for the pressure,

temperature and density, which all increase across a shock wave, and these are

known as the Rankine equations.

we

have reached the limiting case of a sound wave for which there is no change in

the gas properties. Similar expressions can also be derived for the pressure,

temperature and density, which all increase across a shock wave, and these are

known as the Rankine equations.

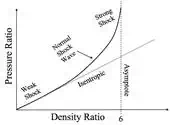

Both the temperature and pressure ratios increase with higher Mach

number such that both ![]() and

and ![]() tend to infinity as

tend to infinity as ![]() tends to infinity. The density ratio

however, does not tend to infinity but approaches an asymptotic value of 6

as

tends to infinity. The density ratio

however, does not tend to infinity but approaches an asymptotic value of 6

as ![]() increases.

In isentropic flow, the relationship

increases.

In isentropic flow, the relationship ![]() between

the pressure ratio

between

the pressure ratio ![]() and

the density ratio

and

the density ratio ![]() must

hold. Given that

must

hold. Given that ![]() tends

to infinity with increasing

tends

to infinity with increasing ![]() but

but ![]() does not, this implies

that the above relation between pressure ratio and density ratio must be broken

with increasing

does not, this implies

that the above relation between pressure ratio and density ratio must be broken

with increasing ![]() , i.e. the flow can no longer conserve

entropy. In fact, in the limiting case of a sound wave, where

, i.e. the flow can no longer conserve

entropy. In fact, in the limiting case of a sound wave, where ![]() , there is an

infinitesimally weak shock wave and the flow is isentropic with no change in

the gas properties. When a shock wave forms as a result of supersonic flow the

entropy always increases across the shock.

, there is an

infinitesimally weak shock wave and the flow is isentropic with no change in

the gas properties. When a shock wave forms as a result of supersonic flow the

entropy always increases across the shock.

Pressure and density ratios across a shock wave

Even though the Rankine equations are valid mathematically for subsonic

flow, the predicted fluid properties lead to a decrease in entropy, which

contradicts the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Hence, shock waves can only be

created in supersonic flow and the pressure, temperature and density always

increase across it.

Designing Convergent-divergent Nozzles

With our new-found knowledge on supersonic flow and nozzles we can now

begin to intuitively design a convergent-divergent nozzle to be used on a

rocket. Consider two reservoirs connected by a convergent-divergent nozzle (see

figure below).

Convergent-divergent nozzle schematic and variations of pressure along

the length of the nozzle

The gas within the upstream reservoir is stagnant at a specific

stagnation temperature ![]() and pressure

and pressure ![]() . The

pressure in the downstream reservoir, called the back pressure

. The

pressure in the downstream reservoir, called the back pressure ![]() , can be regulated using a valve. The

pressure at the exit plane of the divergent section of the nozzle is known as

the exit pressure

, can be regulated using a valve. The

pressure at the exit plane of the divergent section of the nozzle is known as

the exit pressure ![]() , and the pressure at the point of minimum

area within the nozzle is known as the throat pressure

, and the pressure at the point of minimum

area within the nozzle is known as the throat pressure ![]() . Changing the back pressure

. Changing the back pressure ![]() influences the variation of the

pressure throughout the nozzle as shown in the figure above. Depending on the

back pressure, eight different conditions are possible at the exit plane.

influences the variation of the

pressure throughout the nozzle as shown in the figure above. Depending on the

back pressure, eight different conditions are possible at the exit plane.

1. The

no-flow condition: In this case the valve is closed and ![]() . This

is the trivial condition where nothing interesting happens. No flow, nothing,

boring.

. This

is the trivial condition where nothing interesting happens. No flow, nothing,

boring.

2. Subsonic

flow regime: The valve is opened slightly and the flow is entirely

subsonic throughout the entire nozzle. The pressure decreases from the stagnant

condition in the upstream reservoir to a minimum at the throat, but because the

flow does not reach the critical pressureratio ![]() , the

flow does not reach Mach 1 at the throat. Hence, the flow cannot accelerate

further in the divergent section and slows down again, thereby increasing the

pressure. The exit pressure

, the

flow does not reach Mach 1 at the throat. Hence, the flow cannot accelerate

further in the divergent section and slows down again, thereby increasing the

pressure. The exit pressure ![]() is exactly equal to the

back pressure.

is exactly equal to the

back pressure.

3. Choking

condition: The back pressure has now reached a critical condition and

is low enough for the flow to reach Mach 1 at the throat. Hence, ![]() .

However, the exit flow pressure is still equal to the back pressure (

.

However, the exit flow pressure is still equal to the back pressure (![]() ) and

therefore the divergent section of the nozzle still acts as a diffuser; the

flow does not go supersonic. However, as the flow can

not go faster than Mach 1 at the throat, the maximum mass flow rate

has been achieved and the nozzle is now choked.

) and

therefore the divergent section of the nozzle still acts as a diffuser; the

flow does not go supersonic. However, as the flow can

not go faster than Mach 1 at the throat, the maximum mass flow rate

has been achieved and the nozzle is now choked.

4. Non-isentropic

flow regime: Lowering the back pressure further means that the flow now

reaches Mach 1 at the throat and can then accelerate to supersonic speeds

within the divergent portion of the nozzle. The flow in the convergent section

of the nozzle remains the same as in condition 3) as the nozzle is choked. Due

to the supersonic flow, a shock wave forms within the divergent section turning

the flow from supersonic into subsonic. Downstream of the shock the divergent

nozzle now diffuses the flow further to equalise the back pressure and exit

pressure (![]() ). The lower the back

pressure is decreased, the further the shock wave travels downstream towards

the exit plane, increasing the severity of the shock at the same time. The

location of the shock wave within the divergent section will always be such as

to equalise the exit and back pressures.

). The lower the back

pressure is decreased, the further the shock wave travels downstream towards

the exit plane, increasing the severity of the shock at the same time. The

location of the shock wave within the divergent section will always be such as

to equalise the exit and back pressures.

5. Exit

plane shock condition: This is the limiting condition

where the shock wave in the divergent portion has moved exactly to the exit

plane. At the exit of the nozzle there is an abrupt increase in pressure at the

exit plane and therefore the exit plane pressure and back pressure are still

the same (![]() ).

).

6. Overexpansion

flow regime: The back pressure is now low enough that the flow is

subsonic throughout the convergent portion of the nozzle, sonic at the throat

and supersonic throughout the entire divergent portion. This means that the

exit pressure is now lower than the gas pressure (the flow is overexpanded), causing it to suddenly contract once it

exits the nozzle. These sudden compressions cause nonisentropic oblique

pressure waves which cannot be modelled using the simple 1D flow assumptions we

have made here.

7. Nozzle

design condition: At the nozzle design condition the back pressure is low

enough to match the pressure of the supersonic flow at the exit plane. Hence,

the flow is entirely isentropic within the nozzle and inside the downstream

reservoir. As described in a previous post on rocketry, this is the ideal

operating condition for a nozzle in terms of efficiency.

8. Underexpansion flow regime:

Contrary to the over expansion regime, the back pressure is now lower than the

exit pressure of the supersonic flow, such that the exit flow must expand to

equilibrate with the reservoir pressure. In this case, the flow is again

governed by oblique pressure waves, which this time expand outward rather than

contract inward.

Thus, as we have seen the flow inside and outside of the nozzle is

driven by the back pressure and by the requirement of the exit pressure and

back pressure to equilibrate once the flow exits the nozzle. In some cases this

occurs as a result of shocks inside the nozzle and in others as a result of

pressure waves outside. In terms of the structural mechanics of the nozzle, we

obviously do not want shock to occur inside the nozzle in case this damages the

structural integrity. Ideally, we would want to operate a rocket nozzle at the

design condition, but as the atmospheric pressure changes throughout a flight

into space, a rocket nozzle is typically overexpanded at

take-off and underexpanded in space. To

account for this, variable area nozzles and other clever ideas have been

proposed to operate as close as possible to the design condition.