Methods of Jet Propulsion

The types of jet engine, whether ram jet, pulse jet, rocket, gas turbine, turbo/ram jet or turbo-rocket, differ only in the way in which the 'thrust provider', or engine, supplies and converts the energy into power for flight.

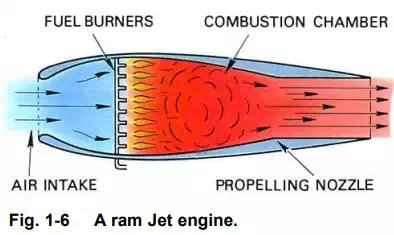

The ram jet engine (fig. 1-6) is an athodyd, or 'aero-thermodynamic-duct to give it its full name. It has no major rotating parts and consists of a duct with a divergent entry and a convergent or convergent-divergent exit. When forward motion is imparted to it from an external source, air is forced into the air intake where it loses velocity or kinetic energy and increases its pressure energy as it passes through the diverging duct. The total energy is then increased by the combustion of fuel, and the expanding gases accelerate to atmosphere through the outlet duct. A ram jet is often the power plant for missiles and .target vehicles; but is unsuitable as an aircraft power plant "because it requires forward motion imparting to it before any thrust is produced.

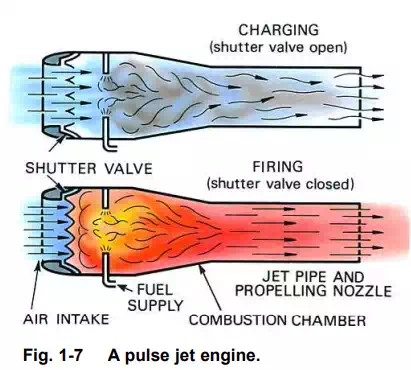

The pulse jet engine (fig. 1-7) uses the principle of intermittent combustion and unlike the ram jet it can be run at a static condition. The engine is formed by an aerodynamic duct similar to the ram jet but, due to the higher pressures involved, it is of more robust construction. The duct inlet has a series of inlet 'valves' that are spring-loaded into the open position. Air drawn through the open valves passes into the combustion chamber and is heated by the burning of fuel injected into the chamber. The resulting expansion causes a rise in pressure, forcing the valves to close, and the expanding gases are then ejected rearwards. A depression created by the exhausting gases allows the valves to open and repeat the cycle. Pulse jets have been designed for helicopter rotor propulsion and some dispense with inlet valves by careful design of the ducting to control the changing pressures of the resonating cycle. The pulse jet is unsuitable as an aircraft power plant because it has a high fuel consumption and is unable to equal the performance of the modern gas turbine engine.

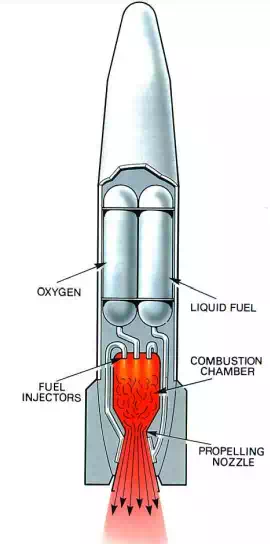

Although a rocket engine (fig. 1-8) is a jet engine, it has one major difference in that it does not use atmospheric air as the propulsive fluid stream. Instead, it produces its own propelling fluid by the combustion of liquid or chemically decomposed fuel with oxygen, which it carries, thus enabling it to operate outside the earth's atmosphere. It is, therefore, only suitable for operation over short periods.

The application of the gas turbine to jet propulsion has avoided the inherent weakness of the rocket and the athodyd, for by the introduction of a turbine-driven compressor a means of producing thrust at low speeds is provided. It draws air from the atmosphere and after compressing and heating it, a process that occurs in all heat engines, the energy and momentum given to the air forces It out of the propelling nozzle at a velocity of up to 2,000 feet per second or about 1,400 miles per hour. On its way through the engine, the air gives up some of its energy and momentum to drive the turbine that powers the compressor.

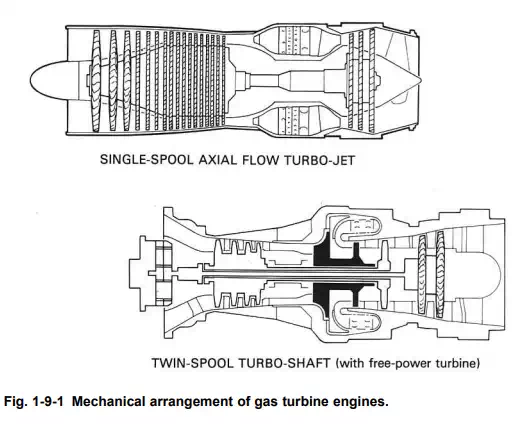

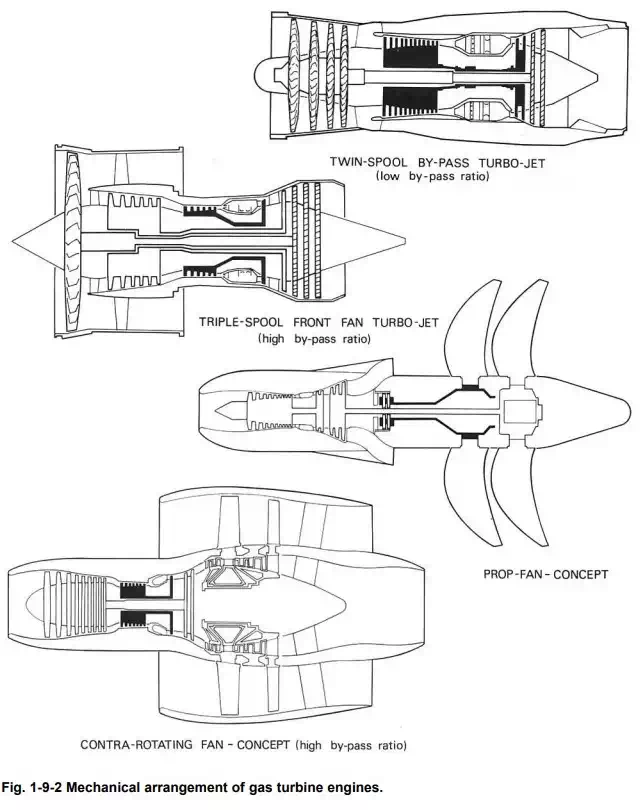

The mechanical arrangement of the gas turbine engine is simple, for it consists of only two main rotating parts, a compressor (Part 3) and a turbine (Part 5), and one or a number of combustion chambers (Part 4). The mechanical arrangement of various gas turbine engines is shown in fig. 1 -9. This simplicity, however, does not apply to all aspects of the engine, for as described in subsequent Parts the thermo and aerodynamic problems are somewhat complex. They result from the high operating temperatures of the combustion chamber and turbine, the effects of varying flows across the compressor and turbine blades, and the design of the exhaust system through which the gases are ejected to form the propulsive jet.

Fig. 1-8 A rocket engine.

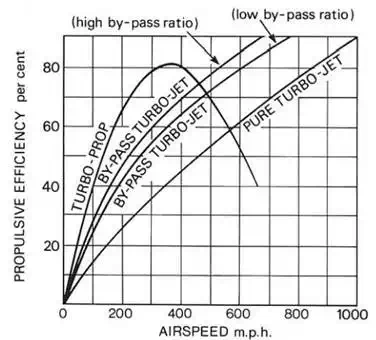

At aircraft speeds below approximately 450 miles per hour, the pure jet engine is less efficient than a propeller-type engine, since its propulsive efficiency depends largely on its forward speed; the pure turbo-jet engine is, therefore, most suitable for high forward speeds. The propeller efficiency does, however, decrease rapidly above 350 miles per hour due to the disturbance of the airflow caused by the high blade-tip speeds of the propeller. These characteristics have led to some departure from the use of pure turbo-jet propulsion where aircraft operate at medium speeds by the introduction of a combination of propeller and gas turbine engine.

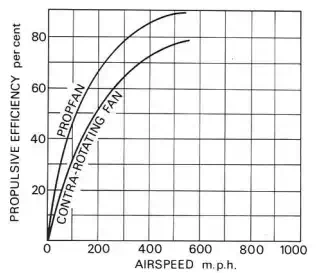

The advantages of the propeller/turbine combination have to some extent been offset by the introduction of the by-pass, ducted fan and propfan engines. These engines deal with larger comparative airflows and lower jet velocities than the pure jet engine, thus giving a propulsive efficiency which is comparable to that of the turbo-prop and exceeds that of the pure jet engine (fig. 1-10).

Fig. 1-10 Comparative propulsive efficiencies.

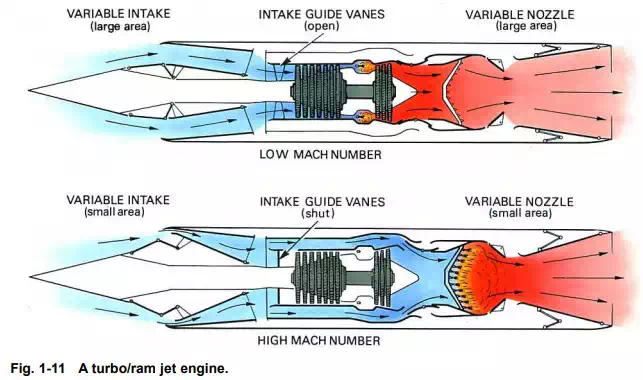

The turbo/ram jet engine (fig. 1-11) combines the turbo-jet engine (which is used for speeds up to Mach 3) with the ram jet engine, which has good performance at high Mach numbers.

The engine is surrounded by a duct that has a variable intake at the front and an afterburning jet pipe with a variable nozzle at the rear. During takeoff and acceleration, the engine functions as a conventional turbo-jet with the afterburner lit; at other flight conditions up to Mach 3, the afterburner is inoperative. As the aircraft accelerates through Mach 3, the turbo-jet is shut down and the intake air is diverted from the compressor, by guide vanes, and ducted straight into the afterburning jet pipe, which becomes a ram jet combustion chamber. This engine is suitable for an aircraft requiring high speed and sustained high Mach number cruise conditions where the engine operates in the ram jet mode.

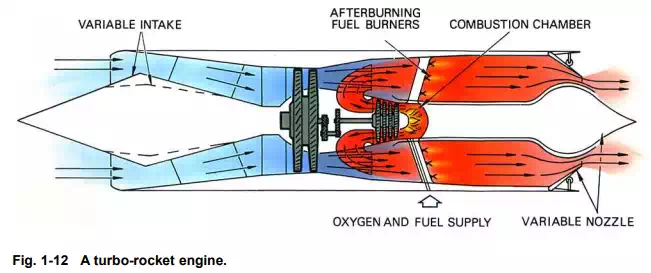

The turbo-rocket engine (fig. 1-12) could be considered as an alternative engine to the turbo/ram jet; however, it has one major difference in that it carries its own oxygen to provide combustion,

The engine has a low pressure compressor driven by a multi-stage turbine; the power to drive the turbine is derived from combustion of kerosine and liquid oxygen in a rocket-type combustion chamber. Since the gas temperature will be in the order of 3,500 deg. C, additional fuel is sprayed into the combustion chamber for cooling purposes before the gas enters the turbine. This fuel-rich mixture (gas) is then diluted with air from the compressor and the surplus fuel burnt in a conventional afterburning system.

Although the engine is smaller and lighter than the turbo/ram jet, it has a higher fuel consumption. This tends to make it more suitable for an interceptor or space-launcher type of aircraft that requires high speed, high altitude performance and normally has a flight plan that is entirely accelerative and of short duration.