Friction Drag

WHAT IS FRICTION DRAG?

Friction

is the resistance that happens when two things rub together—like air against an

airplane. Friction is partly what causes drag.

HOW DOES FRICTION

WORK?

When

an object moves through air, the air closest to the object’s surface is dragged

along with it, pulling or rubbing at the air that it passes. This rubbing

exerts a force on the object opposite to the direction of motion—friction drag.

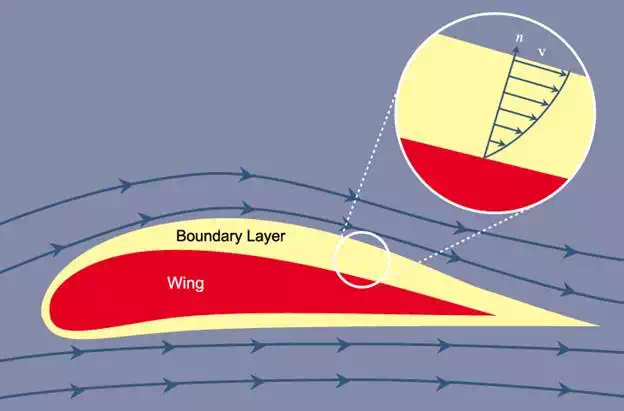

The

thin layer of air closest to the surface of a moving object is called the

boundary layer. This is where friction drag occurs.

The boundary

layer is a very thin layer of air flowing over the surface of an object (like a

wing). As air moves past the wing, the molecules right next to the wing stick

to the surface. Each layer of molecules in the boundary layer moves faster than

the layer closer to the surface. The greater the distance (n) from the surface,

the greater the velocity (V) of the molecules. At the outer edge of the

boundary layer, the molecules move at the same velocity (free stream velocity)

as the molecules outside the boundary layer. Ludwig Prandtl revolutionized

fluid dynamics when he introduced the boundary layer concept in the early 1900s.

AIR "STICKS" TO A WING

Though air is

much less "thick" than, say, honey, like all fluids it has

viscosity—internal friction. The air directly touching the wing does not slip

past it but stays "attached" to it. The air "stuck" to the

wing rubs against the air just above it, which in turn rubs against the air

just above it, and so on, up to the outer edge of the boundary layer.