Typical Aircraft wing and fuselage Structure

According to the current Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 1, Definitions and Abbreviations, an aircraft is a device that is used, or intended to be used, for flight. Categories of aircraft for certification of airmen include airplane, rotorcraft, lighter-than-air, powered-lift, and glider. Part 1 also defines airplane as an engine-driven, fixed-wing aircraft heavier than air that is supported in flight by the dynamic reaction of air against its wings. This webpage provides a brief introduction to the airplane and its major components.

Major components

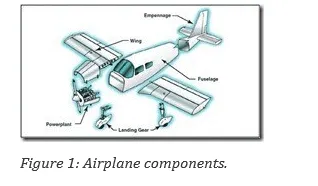

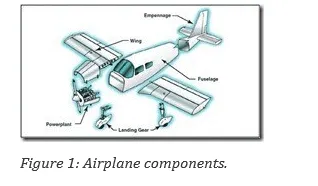

Although airplanes are designed for a variety of purposes, most of them have the same major components.

The overall characteristics are largely determined by the original design objectives. Most airplane structures include a fuselage, wings, an empennage, landing gear, and a powerplant.

Fuselage

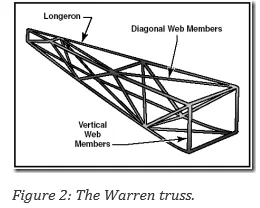

The fuselage includes the cabin and/or cockpit, which contains seats for the occupants and the controls for the airplane. In addition, the fuselage may also provide room for cargo and attachment points for the other major airplane components. Some aircraft utilize an open truss structure. The truss-type fuselage is constructed of steel or aluminum tubing. Strength and rigidity is achieved by welding the tubing together into a series of triangular shapes, called trusses.

Construction of the Warren truss features longerons, as well as diagonal and vertical web members. To reduce weight, small airplanes generally utilize aluminum alloy tubing, which may be riveted or bolted into one piece with cross-bracing members.

As technology progressed, aircraft designers began to enclose the truss members to streamline the airplane and improve performance. This was originally accomplished with cloth fabric, which eventually gave way to lightweight metals such as aluminum. In some cases, the outside skin can support all or a major portion of the flight loads. Most modern aircraft use a form of this stressed skin structure known as monocoque or semimonocoque construction.

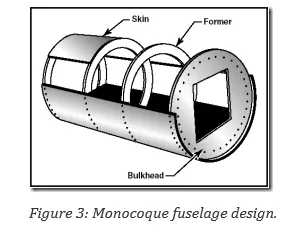

The monocoque design uses stressed skin to support almost all imposed loads. This structure can be very strong but cannot tolerate dents or deformation of the surface. This characteristic is easily demonstrated by a thin aluminum beverage can. You can exert considerable force to the ends of the can without causing any damage.

However, if the side of the can is dented only slightly, the can will collapse easily. The true monocoque construction mainly consists of the skin, formers, and bulkheads. The formers and bulkheads provide shape for the fuselage.

Since no bracing members are present, the skin must be strong enough to keep the fuselage rigid. Thus, a significant problem involved in monocoque construction is maintaining enough strength while keeping the weight within allowable limits. Due to the limitations of the monocoque design, a semi-monocoque structure is used on many of today´s aircraft.

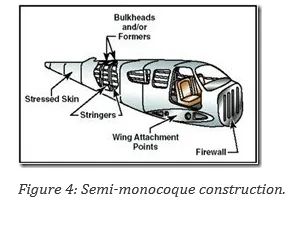

The semi-monocoque system uses a substructure to which the airplane´s skin is attached. The substructure, which consists of bulkheads and/or formers of various sizes and stringers, reinforces the stressed skin by taking some of the bending stress from the fuselage.

The main section of the fuselage also includes wing attachment points and a firewall.

On single-engine airplanes, the engine is usually attached to the front of the fuselage. There is a fireproof partition between the rear of the engine and the cockpit or cabin to protect the pilot and passengers from accidental engine fires. This partition is called a firewall and is usually made of heat-resistant material such as stainless steel.

Wings

The wings are airfoils attached to each side of the fuselage and are the main lifting surfaces that support the airplane in flight. There are numerous wing designs, sizes, and shapes used by the various manufacturers.

Each fulfills a certain need with respect to the expected performance for the particular airplane.

How the wing produces lift is explained in aerodynamics pages.

Wings may be attached at the top, middle, or lower portion of the fuselage. These designs are referred to as high-, mid-, and low-wing, respectively. The number of wings can also vary. Airplanes with a single set of wings are referred to as monoplanes, while those with two sets are called biplanes.

Many high-wing airplanes have external braces, or wing struts, which transmit the flight and landing loads through the struts to the main fuselage structure. Since the wing struts are usually attached approximately halfway out on the wing, this type of wing structure is called semi-cantilever. A few high-wing and most low-wing airplanes have a full cantilever wing designed to carry the loads without external struts.

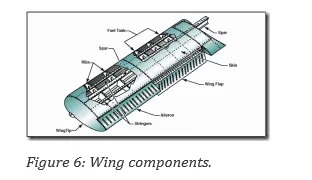

The principal structural parts of the wing are spars, ribs, and stringers.

These are reinforced by trusses, I-beams, tubing, or other devices, including the skin. The wing ribs determine the shape and thickness of the wing (airfoil). In most modern airplanes, the fuel tanks either are an integral part of the wing´s structure, or consist of flexible containers mounted inside of the wing.

Attached to the rear, or trailing, edges of the wings are two types of control surfaces referred to as ailerons and flaps. Ailerons extend from about the midpoint of each wing outward toward the tip and move in opposite directions to create aerodynamic forces that cause the airplane to roll. Flaps extend outward from the fuselage to near the midpoint of each wing. The flaps are normally flush with the wing´s surface during cruising flight. When extended, the flaps move simultaneously downward to increase the lifting force of the wing for takeoffs and landings.