Improving Profits

A company's accounting records and financial statements are based on accounting principles, concepts, detailed rules, etc.

For example, because of the cost principle and the monetary unit assumption a company's accounting records consist only of items that were acquired in a past transaction. Those guidelines also mean the recorded items are usually reported at an amount that is no higher than their cost at the time of the transaction. While this may be convenient for auditors, who can verify past transactions instead of determining current values, it is not helpful for people who must make decisions.

Decisions—including those to improve profits—involve the present and the future. (No decision can undo the past.) Accordingly, the decision maker needs current and future amounts. Always keep in mind that the numbers in a company's general ledger are all past, historical, or sunk amounts. Some of these historical amounts may be completely irrelevant, while others may be useful if they are adjusted to the present and future.

Fortunately, only a limited quantity of numbers may be necessary in order to make the correct decision. For example, if the executive team's compensation will not change if the product line is expanded, then the executive team's compensation is not relevant and does not have to be brought into the analysis on the expansion.

We will use short cases to illustrate the relevant amounts necessary to make decisions for improving profits. You should also be mindful that people from disciplines other than accounting may have different solutions for the situations. Lastly, slightly different situations could result in vastly different outcomes than those presented.

Past Amounts May Not Be Relevant

As stated in the introduction, all decisions (including the ones that will lead to improved profits) involve the present and the future. No decision will undo the past. Since the amounts in the company's accounting records are history, you need to be careful when using them to make decisions.

Story #1: Replacing a Recently Purchased Printer

We will use the following story to illustrate the point that past amounts (including those in the company's general ledger) are usually irrelevant when making decisions. Several months ago, a one-person company bought a very unique, state-of-the-art printer for $2,000. We will refer to it as the "original printer." The owner spends two hours out of her 10-hour day using the original printer to generate significant profits. Today a more advanced model of the printer has become available. The advanced model sells for $2,100 and it will cut the owner's time in half from two hours to one hour per day. Other costs to operate the printers are identical.

The owner believes that she needs to personally operate the printer (as opposed to delegating the operation to another person) in order to maintain the company's reputation for superb quality and customer service. If the owner obtains the advanced model, the hour saved each day will be used to generate additional revenues from existing customers.

Numbers contained in the company's general ledger:

· Cost of the original printer: $2,000.

· Perhaps a small amount of depreciation on the original printer. (If the company prepares financial statements only at the end of the year, it is probably too soon to find any depreciation recorded.)

· The salary and benefits expense of the owner if the company is a corporation. (If the company is a sole proprietorship, there will be no compensation expense for the owner. Rather, there will be a balance sheet account to keep track of the owner's draws.)

· Expenses of operating the original printer.

Important numbers not in the company's general ledger:

· The value of one hour of the owner's time. (The additional profit earned from the additional hour.)

· Money that will be received from disposing of the original printer.

· Expenses of operating the advanced model.

· The future salary of the owner.

Analysis:

· The original printer works as well as it did when it arrived.

· The original printer is somewhat obsolete due to the technology built into the advanced model.

· The $2,000 paid for the original printer is gone; it is history. No decision will undo the purchase of the original printer.

· Today's option is to obtain the advanced, more productive model by paying up to an additional $2,100. (The amount could be less than $2,100 if the company receives money for its original printer and/or receives a tax benefit on the disposal of the original printer.)

· The hour of owner's time saved each day in the printing operation is expected to convert into $100 per week of additional profit from the additional revenues generated.

Decision for profit improvement:

· The decision is relatively straight forward: Should the company spend up to $2,100 (assumes that the original printer cannot be sold) in order to free up one hour per day of the owner's time? Freeing up one hour of the owner's time is expected to generate $100 per week of additional profit. $100 per week is $5,200 per year of additional profit on a $2,100 investment. This is an enormous rate of return.

Irrelevant numbers that confuse the decision:

· The past cost of the original printer, $2,000. This cost is sunk. Don't think about it; it is history.

· The owner's salary. Because the owner's salary will not change if the advanced printer is purchased, her salary is not relevant to the decision.

· The expenses (other than the person operating the printer) of operating the printers. These expenses are irrelevant because they are going to be identical whether the original printer or the advanced model is used.

Amounts Unchanged Are Irrelevant

As we had just seen in story #1, the amounts that did not change with the decision are irrelevant and can be omitted. Let's illustrate that point further with Story #2.

Story #2: Adding Menu Items to a Bakery

Let's assume that you own a bakery that has excellent breads, pastries, and specialty cakes. For the past eight years sales have not been "rising" and your profit is slipping. Your industry magazine has been featuring articles on bakery cafes. Until now you have not sold soups, salads, sandwiches or beverages. The magazine articles have you thinking about adding these items in order to restore some of the vanishing profits.

Your decision is:

(a) keep your bakery as it is, or,

(b) add soups, salads, sandwiches, and beverages to your existing business.

The relevant numbers are:

· Current and future numbers that will change if soups, salads, sandwiches, and beverages are added. (Examples include the additional sales and the additional expenses—such as ingredients for the soups, meats and vegetables for sandwiches, beverages, paper goods, a sales clerk at lunch, depreciation on any remodeling and/or furnishings, etc.)

The irrelevant numbers are:

· All past numbers.

· Numbers that will remain unchanged after soups, salads, sandwiches, and beverages are added. (Examples might be the rent, salaries and fringes of bakers, depreciation, membership dues, etc.)

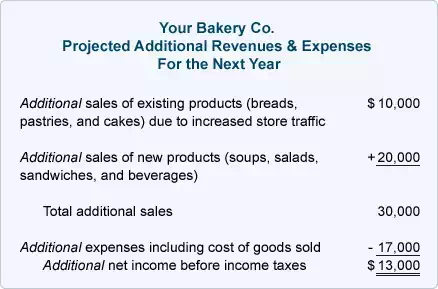

Listing only the items and amounts that would change, the analysis might look like this:

Since these are current or future items and the only amounts that will change, these are the relevant amounts. However, it is imperative that you remember that these are projections. If these projections become a reality, your business would see its net income before taxes increase by $13,000. If the sales are not achieved or costs are not controlled, the net income amount could be significantly lower... perhaps a negative amount.

Prior to making these projections you should have done some research with present customers. In addition, you should call on companies to see if they have any interest in: the new expanded menu, purchasing boxed lunches on your artisan breads for business lunches, or ordering pastry and fruit platters for other meetings, etc. The projections should be realistic and achievable.

How Expenses Change

As a company's sales or revenues increase, some of the company's expenses will increase and some expenses will not change. For example, if a company sells a few additional products on which it pays a sales commission, the company's cost of goods sold will increase as will its commissions expense. On the other hand, the salaried officers of the company and the company rent will not increase even a penny with the sale of a few more products. To help improve the profits at a company, it is valuable to know how the expenses behave—will they increase when sales increase or will they stay at the present amount. The goal is to increase sales or revenues by an amount greater than the increase in expenses. Another approach is to decrease expenses by an amount greater than a related decrease in revenues.

Expenses can be classified according to how they react to a change in revenues. Often, we see three classifications of expenses:

- Variable

- Fixed

- Mixed

To help explain these three types of expense behavior, we will use the example of Verve Company, a women's retail clothing store.

1. Variable expenses change in total as volume changes.

A sales commission is considered to be a variable expense. For example, let's say that instead of a salary, Verve pays its sales staff commissions equal to 10% of sales. When sales are $50,000 Verve has $5,000 of commissions expense; when sales are $70,000 Verve has $7,000 of commission expense.

With a variable expense the amount per unit (or the percent) stays constant—in this case it's 10%—but the total expense will vary with the sales volume.

You can see this with the cost of goods sold. Let's say Verve pays $7 for a particular shirt and then sells the same shirt for $10. When sales are $100, the cost of goods sold is $70; when sales are $10,000, the cost of goods sold is $7,000. Other variable expenses could include delivery expenses, wages in the shipping department, and shipping supplies used such as boxes, shrink wrap, etc.

2. Fixed expenses do not change in total as volume changes.

If Verve rents retail space for $2,500 per month, the rent remains at $2,500 whether the sales are at an all-time high or an all-time low. If Verve owns the space, the real estate taxes remain the same whether sales are high or low. Other examples of fixed expenses include such things as salaries, insurance, telephone book advertising, and most depreciation.

If sales were to increase by a huge percentage, some fixed expenses might change. For example, if sales doubled it is likely to cause an increase in rent expense.

3. A mixed expense is a combination of a variable and a fixed expense.

Let's say Verve employs a sales person who is paid a base salary of $2,000 per month plus a 2% commission on all sales. The base salary is a fixed expense; the 2% commission is a variable expense. Taken together, the salesperson's compensation is considered a mixed expense.

Some mixed expenses do not correlate with sales. Let's take the example of vehicle expenses. If a salesperson uses her car to make sales presentations to customers, expenses such as insurance, licenses, parking, and some depreciation are all fixed expenses—they stay the same within a reasonable range of miles driven, or regardless of the amount of sales. Some vehicle expenses, such as gasoline, oil changes, tires, and other maintenance will vary with the number of miles driven. But, will these expenses vary with sales? Maybe or maybe not.

To help determine (1) how much of a mixed expense is fixed and (2) the rate at which the variable portion of a mixed expense will change as some activity changes, accountants use a statistical tool called regression analysis. Consult a statistics textbook to learn more about this valuable tool.

Business Stories #3 — #4

Let's relate the profit improvement concepts discussed in Story #1 to some additional situations. In each story below, a company must make one or more decisions to achieve its goal of improving profits (or reducing its losses).

Story #3: The Bridal Boutique Considers Opening a Second Store

The City Center Mall—which had been in decline for a number of years—was recently purchased by a dynamic developer and some new upscale stores are opening there. Jane Jones owns the Bridal Boutique, a wedding and formal dress store located in the suburbs. She is being recruited by the new mall owner to open up a second store in the revitalized City Center Mall. Jane is being offered a lease that requires no security deposit and no fixed rent expense—instead, the rent would be a variable expense of 9% of sales and be due 15 days after the end of a month (e.g., on May 15, Jane would pay the landlord 9% of April's sales.)

Jane estimates the total variable expenses to be 75% of sales. (This includes rent at 9% of sales, cost of merchandise sold at 50% of sales, and assorted other variable expenses of 16% of sales.)

Jane estimates that monthly fixed expenses will amount to $5,000 per month (salaries, some wages, telephone, and some advertising). Her existing store in the suburbs is leased at a fixed monthly rent expense of $3,000. The sales at that store average $300,000 per year and would not be affected by the new store in the City Center Mall.

Jane studies the profile of the mall neighborhood and sees that new condominiums are selling quickly. Based on the sales records of previous and current mall tenants and the records of her existing store, Jane conservatively estimates her sales at this new location will be $400,000 per year. Jane's banker advises against opening the additional store based on his past experiences with other clients facing similar choices. Jane's intuition, however, tells her that the additional location with the variable rent is just too good to pass up.

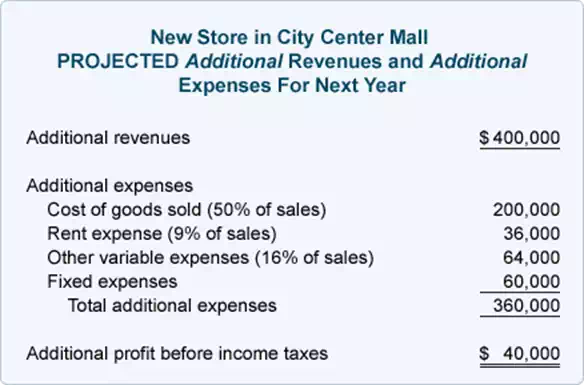

Below is the analysis Jane uses to make her decision.

Since the existing store's sales and expenses will not be affected by the new location, they are not relevant and were omitted in the analysis. The Bridal Boutique's high quality merchandise, favorable prices, and tightly controlled expenses are not part of the analysis either because they exist with or without the new location.

It is, of course, imperative that Jane use realistic numbers in her analysis—sales must be clearly attainable, and controls must be in place to keep expenses within their planned range. If the above amounts are realized, opening this second Bridal Boutique store will give Jane an additional profit before income taxes of $40,000.

Although her analysis shows that she will be improving profits, Jane also needs to be concerned with cash flow. The circumstances at the new store are such that rent is paid 15 days after the month is over, employees are paid one week after the two-week work period ends, and merchandise is paid for 30 days from purchase. Customers at Jane's new location will purchase goods using cash and credit cards. Jane is also able to turn her inventory every 30 days. As a result of these conditions, Jane is confident that her cash flow will be positive.

Jane decides to open this second Bridal Boutique store and finds it to be successful. The situation worked out very well thanks to specifics such as the high level of mall traffic and the rent amount charged as a percentage of sales.

Story #4: The Daily Grind Cafe Considers a New Location

Bob Smith owns several locations of the Daily Grind, a cafe and sandwich shop. Bob concludes that he should close one of his locations at the end of its lease because of disappointing sales. The store is no longer in a prime location and the poor sales do not warrant the fixed rent expense of $3,000 per month.

Because Bob has some loyal customers, he inquiries about renting space in a new development within a mile of the old location. That new development, however, has already signed tenants who would compete with Bob for the same customers. In addition, there are more competitors who just opened stores within several miles of the new development. The space available for his cafe in the new development requires a long-term lease and a monthly rent expense of $3,800.

Bob estimates that annual sales at the new cafe would be approximately $300,000. Cost of goods sold would be 50% of sales and other variable expenses would be 16% of sales. In addition to the rent of $3,800 per month, there would be fixed expenses (primarily salaries and wages) of $5,000 per month.

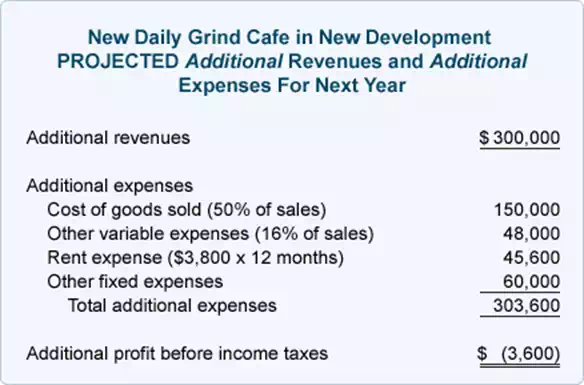

To help make the decision on whether or not to open the new cafe, Bob prepares the following analysis of additional revenues and additional expenses:

Instead of improving profits, the projections reveal an annual loss of $3,600—not a very good exchange for Bob's additional risks and commitments in opening a cafe in the new development. When Bob's accountant advised him against opening the cafe, she detected that Bob really wants additional annual sales. She suggests that Bob shift his focus from sales (the top line of the income statement) to net income (the bottom line of the income statement).

By focusing on the bottom line, Bob may find that he can get additional net income without the long hours, staffing challenges, uncertain sales, and high fixed expenses of a new location.

Business Stories #5 — #8

Story #5: The Daily Grind—An Innovative Sales Channel

We continue with Bob's situation from Story #4:

Instead of focusing on adding sales to the top line of the income statement, Bob's accountant convinced him to focus on improving the bottom line. She said that Bob should put his energy into looking for modest amounts of profitable sales rather than large amounts of unprofitable sales. Bob did this by:

· reviewing his existing expenses by using a standard or benchmark (discussed in Story #6 below), and

· only adding sales when the related expenses are smaller than the sales.

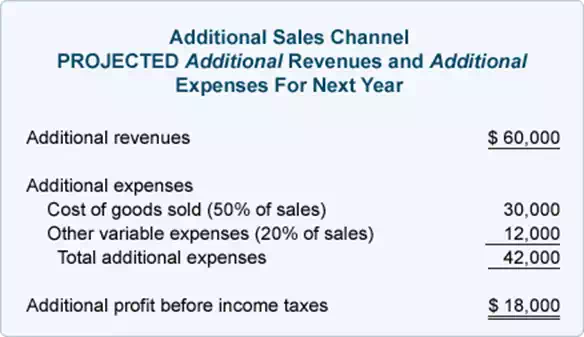

Bob identifies a way to sell his coffee and sandwiches using direct delivery rather than retail space. This new system will not involve additional rent since the products will be delivered from one of Bob's existing locations. In fact, the only additional expenses for these sales will be the cost of the products (50% of sales value) and the expense of obtaining and delivering the orders (estimated to be 20% of sales). Bob believes he could also add a delivery fee to offset some of the delivery expense and to discourage small orders. Excluding the delivery fee revenues, Bob estimates that $60,000 of sales could be generated from this new sales channel.

With the help of his accountant, Bob prepares the following analysis focusing on additional revenues and expenses:

Bob was amazed to see that just a modest increase in sales could improve profits by $18,000. This is significantly different than the loss projected from opening an additional retail space discussed in Story #4. This profit improvement occurs because Bob did not have to add any fixed expenses. In short, this modest sales increase meant more profit, less stress, and less risk than adding another retail cafe.

Story #6: Nelson Manufacturing—Comparing Hours to the Industry Standard

Nelson Manufacturing is a small company staffed by two salaried employees and two hourly-paid employees. Sales fluctuate seasonally—the company is profitable during spring, summer, and early autumn, but the company suffers losses in late autumn and winter when sales drop off sharply and production declines. The company's products are such that they cannot be stored for future sales.

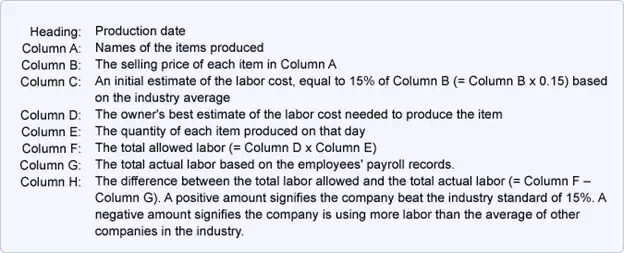

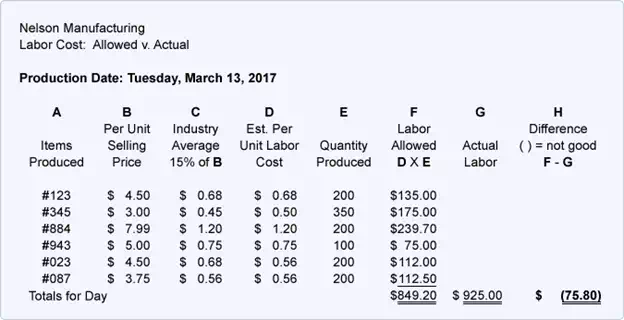

Susan Nelson, the owner, recently reviewed statistics from companies within the same industry as Nelson Manufacturing. The statistics show that on average the labor needed for producing an item equals 15% of its sales value. Susan is curious to compare her company's labor cost as a percentage of sales to the industry standard. There is no time or money for an elaborate cost accounting study, so Susan's accountant prepares a simple electronic worksheet to be filled in after each day's actual production. The worksheet lists the following:

The worksheet for Nelson Manufacturing's production of March 13 is shown here:

Each day a worksheet is prepared for the previous day's production. Upon analysis, Susan realizes that her company is using more hours than the industry average to fill production orders. The company is paying workers for hours it does not need—hours that should be eliminated when production volume decreases. In effect, losses due to paying unnecessary wages in the slower months were eating up profits made in the busier months. In order to be competitive with the industry and avoid a net loss on the fall and winter income statements, Susan must immediately reduce worker hours whenever production volume declines.

The accountant explained to Susan that managing the relationship between payroll costs and output is not restricted to manufacturers—many retailers and service companies use part-time employees to work during the busiest hours of the day (or busiest seasons of the year) and then send them home from work when sales or customer counts are down. This is especially true for national companies whose stock is publicly traded—they want to meet earnings-per-share targets, and that will only happen if expenses are reduced when sales decline.

Story #7: Eastland Manufacturing—The Value of a Database

Eastland Manufacturing Company produces component parts for other manufacturers and employs forty people in its production department. Some employees are more productive than other employees, and some parts require more time to produce than other parts.

Eastland is asked to submit a bid (quote a price) for producing a new part similar to a component Eastland already produces (Part #3456). The preparation of the bid is greatly facilitated by Eastland's computerized database which allows a manager to look up production records specific to Part #3456. Under the part number are entries for each time the part was produced, and each entry shows the number of parts produced, the hours spent producing the parts, the average number of parts produced per hour, and the employee that produced the parts. An average can be retrieved for any time period desired.

While this information is obviously valuable when preparing a bid for a new part, a database can also be useful in monitoring productivity. For example, a manager can use a database to more objectively review an employee's productivity record—information that is helpful when determining productivity bonuses or deciding whether or not a recent hire should become a permanent employee.

Story #8: Strategies Other Than Cost Control

Improving profits is not limited to controlling costs—sometimes strategies such as better training for employees can reap significant rewards.

For example, one national retail chain electronically monitors the number of people entering each of its stores. Because its cash registers record the time of each sale, the retailer can determine—for any given time period—the percentage of people entering the store who actually make a purchase (the "conversion rate"). If a store has a low conversion rate, the employees are coached on better methods of engaging their customers, thereby increasing sales. This company realizes that a small increase in the conversion rate will result in a significant increase in sales. Since most of the store's expenses are fixed for that short time period, the cost of the goods sold may be the only increase in expenses associated with the additional sales. The result will be a dramatic increase in profits.